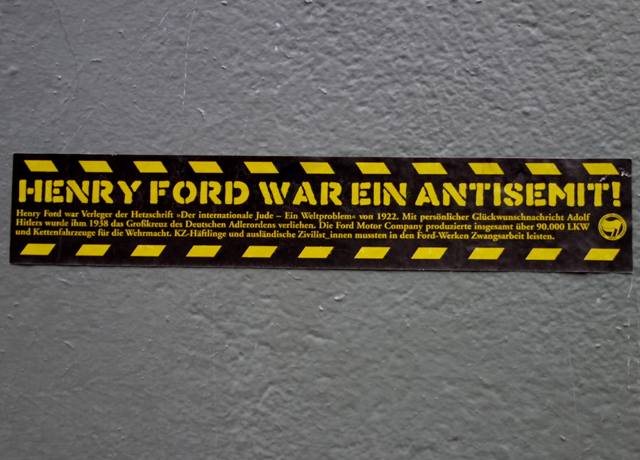

Bluntness can be a masquerade. The declaration here is unequivocal: “Henry Ford was an anti-Semite.” And the supporting evidence laid out below is hard to argue with. Ford did publish The International Jew, a pernicious slander that won the admiration of the future Führer. These are facts. But what does it mean to share them in this manner?

As is true throughout most of Europe, anti-Muslim feelings are the dominant form of ethnic discrimination in contemporary Germany. Although members of the far right periodically invoke their animosity towards Jews, whether as a way to recall their past strength or to rail against government bans on hate speech, it is clear that the best way to increase their numbers is to target poor immigrants from Turkey, North Africa and the Middle East.

While Israel has done itself no favors in recent years from a public-relations standpoint, structural reasons make it difficult for Europeans anxious about Islam to hate the country: the enemy of one’s enemy may not be one’s friend, exactly, but it is usually exempt from irrational antipathy. Indeed, the people in Europe most likely to complain about Israel and, by extension, the diaspora that sustains it, are leftists.

Since the 1960s, when the Palestinian cause first became fashionable, European leftists have felt empowered to voice sentiments that their more conservative neighbors feared to utter. Self-assured in their righteousness, they have felt emboldened to make claims that would be considered anti-Semitic if they came, instead, from conservatives.

Given this history and the prevalence of pro-Palestinian street art in leftist haunts, this reminder of Henry Ford’s pernicious influence seems out of step with the times. Or at least out of place. On first read, this seems more like the sort of message that eager American college students on the left would spread to shock their complacent peers.

But if we scrutinize the fine print, a different possibility emerges. It doesn’t just inform us of Ford’s role in publishing The International Jew and note that Hitler awarded him the Grand Cross of the German Order of Eagles in 1938, but also points out his corporation’s contribution to the German war effort: “The Ford Motor Company produced over 90,000 trucks and half-tracks for the Wehrmacht overall. Concentration camp detainees and foreign civilians had to perform compulsory labor in Ford plants.”

These fact are also indisputable. Whether they should be tied to Henry Ford’s personal anti-Semitism, however, is not as clear. A number of American corporations had subsidiaries in Germany that continued operations during the war. And some, like IBM, whose business equipment helped keep German operations running efficiently, are also frequently described as being tainted by the Holocaust.

For many leftists in the 1920s and 1930s, the superficial opposition between fascism and capitalism – the Nazis did, after all, call themselves National Socialists — was an illusion propagated to facilitate their working together. The fascist state was merely a more extreme version of the government in every nation where capitalism reigned supreme, pushing a brand of xenophobic patriotism meant to distract citizens from their own loss of economic and political power.

This argument was hotly disputed between the wars and remains controversial today, with more conservative political theorists insisting that capitalism must be the enemy of all forms of totalitarianism, whether on the left or the right. Those with a libertarian bent have pursued this line of reasoning with particular vigor, implying that any strong state, even the superficially innocuous sort developed during the Great Depression in the United States, will necessarily tilt towards tyranny.

Henry Ford and Fordism, the mode of one-size-fits-all capitalism his company pioneered while manufacturing the Model T, are crucial elements in this debate. It’s no accident that both Hitler and Stalin were drawn to the combination of standardization and economy of scale made possible by Ford’s assembly line. Nor is it surprising that Americans eventually bridled, during the height of the Roaring Twenties, at the lack of choices Ford gave them.

Through a dizzying series of twists and turns, one of the greatest capitalists in the history of the world came to seem almost like a socialist, more oriented to demographic masses than the individuals who comprised them. Ford’s anti-Semitism, while outwardly populist – he claimed to be defending the common man against the predations of international financiers and their ilk – could also be seen as a hatred of diversity, the freedom to not be like everybody else.

So where does that leave us with this curious artifact, a street bulletin in Berlin, urgently communicating news that was old in 1950? If we reflect on the variety of ways in which populist rhetoric from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century has been repurposed by social movements of the past half decade — from anti-EC protests in Europe’s “South” to Occupy Wall Street and its multitudinous offshoots to the long Arab Spring blooming again in Egypt – we might interpret this reminder of Ford’s unsavory past as a cautionary tale, suggesting that the line between populism and totalitarianism is more permeable than we might like to think.

Perhaps, via a discursive strategy that Germans of all sorts have had recourse to master since the end of World War II, this anachronistic attack on Henry Ford is yet another way to imply that Americans are partially responsible for fascism and, by extension, that the American government is at the vanguard of its resurgence today.

Or maybe this seemingly blunt communiqué is intended to inspire a less simplistic allegorical reading, in which contemplation of the relationship between Ford and fascism between the wars will eventually lead to insight about its contemporary equivalents. If Henry Ford was X, what is Bill Gates or Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg? It doesn’t take a degree in advanced hermeneutics to read these men’s corporate populism, in which customers are encouraged to share, but only in circumscribed ways, as the flip side of the post-9/11 surveillance state: you can have your privacy in any color you want, so long as its transparent.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.