Apologists are always the same. Whether they’re rationalizing war crimes, or promoting reactionary ideologies, they always feign distance from what’s being defended. Why do they insist on appearing impartial? It never works for me. Rats always smell like rats. There’s no disguising them. I’m not the only journalist who feels this way.

Personally, it’s a learned response, inculcated by years of déjà vu when listening to spokespersons from the US and Russian governments insist that criticisms of their military conduct, in the Middle East, or in the North Caucasus, is politically motivated. The idea that a state representative, particularly of said powers, is somehow above it all, that they can distinguish between fact and fiction, never ceases to leave reporters cold. But they continue with charade, as though impervious, as though someone actually believes them.

State broadcasters, of course, are especially guilty of such theatre. You can understand why. Unlike a press officer, they’re tasked with preparing a more legitimate-sounding assignment: journalism. Nonetheless, episodes of Russia Today, for example, will appear as transparently propagandistic as anything produced by Pravda during the Cold War. If only the problem was limited to the public sector. I frequently experience the same reading corporate press in the West, like The Wall Street Journal, and The Jerusalem Post. Misleading is the adjective that always come to mind.

Whether state-owned or private, the themes are depressingly similar: Innocent people plagued by terrorism. Good versus evil stories, designed to appeal to the emotions. Attacks on doubters of government policies, as though there is always a Third Column at work, that must be discredited. It’s instantly familiar. And it reeks of twentieth century authoritarianism. But the methodology is revealing. Every time it’s used, discerning journalists suspect that the state has something to hide.

I detected a familiar smell this week, when I first read about Burmese government denials of ethnic cleansing. Facing down a compelling body of evidence attesting to the veracity of such charges, President Thein Sein could only issue a hollow, one-line remark about “smears.” To say that it reeked of caricature would be the understatement of the year. At least in Burma.

Sein said nothing of the fact that mass graves were documented by Human Rights Watch in its extensive 153 page report “All you can do is pray” which was published in April, or disclosures that state forces dumped dead bodies with all the hallmarks of summary execution in IDP camps. Or even that the President’s own spokesman appeared to openly back violence against the minority targeted by mob violence. Instead, these charges were “smears.”

I might as well have been in Colombo. One of my longstanding beats is another troubled Asian democracy, Sri Lanka. Thein Sein’s apologetics brought back memories of the various statements that defenders of Sri Lanka’s brutal Rajapaksa regime have proffered, in response to reports by the press, by the United Nations, by the International Crisis Group, and Amnesty International, indicating that Sri Lanka committed a host of brazen war crimes in 2009. The only thing different, really, was the country.

Here’s why: Sri Lanka’s recurrent response has been to allege or imply that all the mentioned parties are in league with their defeated foes, the brutal separatist rebel group known as the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam,) or that they are motivated by some other squalid, malicious impulse. The utility of this narrative is obvious: the criminal becomes the victim, and extremely damning evidence is booted out of the spotlight. Sound familiar?

It strikes me that typically, such conspiracy theories or comparably risible attempts at refutation- rarely if ever served up with any evidence- are aimed at the defendant’s constituency by way of an assault on their accusers. This is because most neutral parties will look at the evidence first. That is, if they have don’t have their access to it somehow limited. But for a domestic audience with legitimate grievances, the situation is entirely different.

For example, in the case of Sri Lanka, an ethnic majority Sinhala population that has had to put up with several decades of war and suicide bombings by the LTTE that have frequently killed innocent people are going to be responsive to claims their highly tenacious former enemies may still wish them ill. The LTTE was indeed funded through an international network and managed to even operate its own de facto navy and air force at the height of its powers.

Thus the Sinhala population of the island would be likely to be responsive to their government’s official line- as they have proven to be. And the use of such conspicuously desperate propaganda, which seems like PR suicide to many, begins to demonstrate its rational purpose.

Needless to say, such performances, while attempting to efface or distract from the available evidence, do not refute it. With regard to Sri Lanka, it remains the case that NGO sites and makeshift hospitals that gave their GPS co-ordinates to the Sri Lankan government were repeatedly shelled, whereas those that did not, were not. That the Defence minister of the country openly declared a hospital to be a legitimate target and that a senior government official acknowledged that international law was breached in conversation with a US diplomat. Yet the government still sticks rigidly to the official line, more or less denying that they did anything wrong at all, attacking journalists who confront them on salient issues.

One of the more vocal of these defenders has been the former Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations, and consul-general in Sydney, Australia, Bandula Jayasekara, with whom I had an exchange on Twitter in recent weeks. In response to a series tweets of his, in which he libels the Channel Four filmmaker Callum Macrae (this is a later example, but a good one) I asked Mr Jayasekara if he had any evidence for his claims. He provided none, but went on to say:

To which I replied:

Jayasekara did nothing to refute my statement. This disregard for the evidence, and an appeal to the viscera, is an old tactic – one well suited to Twitter given the restraints of the units of conversation. But one that has dangerous consequences.

Such disinterest in facts appeals to our worst instincts. In countries with tainted pasts and a history of recurrent ethnic conflict, time and again the stronger party has resorted to this tactic, instead of soberly attending to accountability, redress and reconciliation. In the long term, such an approach is totally counter-productive for peace, but has its own false economy: it is cheap and easy to inculcate nationalist feeling in return for passing political capital.

The result is so often continuing rancor between the affected ethnic groups, and in some cases a deepening of ultranationalist or cultural chauvinism. One example of this with regard to Sri Lanka was demonstrated in a recent cricket match at the Oval in London. Tamil protesters flying a flag that many associate with the LTTE (but others contend is a symbol for their envisaged future state Tamil Eelam) were assaulted by a group of Sri Lankan cricket fans. A video of the confrontation (see below) emerged online, as did a photograph of a man appearing to kick a woman with her backed turned to him uploaded to Facebook with the words “KEEP CALM AND KICK LTTE BITCHES.” The latter picture received many approving comments.

Other videos show the two parties separated from one another, jeering across the street. This micro-event in embodies many aspects of the state of relations between the two communities in the wake of the war. Especially with the denials, and the lack of accountability from the government. Without justice, hatred grows, and both sides antagonize each other to ensure it continues to do so. The consequences could be very bad, obviously, and the portents are ominous.

What is it in human nature that longs to simplify reality so, especially in matters concerning race and nationality? We’re looking to anesthetize ourselves, on some level, to the failings of reality, I wager. By providing meaning and certainty – especially in relation to personal identity – in the face of the complexity we’re confronted with. By associating “us” with the ideals that one wants to aspire to, and the ego with a perfect national image, our defenses are bolstered, and we’re affirmed the right to honor our worst impulses collectively, without restraint.

Given a credulous population, and a handy scapegoat, presented with a sense of threat, by some proposed international network opposed to “our” civilization and common good, we have all the ingredients we need to blame the other for oun own failings. Indeed, the more the psyche is invested in such ritual narratives, the more addictive they can become- and the more hysterically they will be defended.

From the war on terror to common racism, the genocidal shock troops of Slobodan Milosevic to the English Defense League, one can see all the hallmarks of this poisonous and archaic impulse. The popularity of nationalism, and its corresponding prejudices, is rooted in their appeal to our predilection for denial. Which brings to mind Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s appeal to his readers in his legendary Gulag Archipelago:

“Let the reader who expects this book to be a political expose slam its covers shut right now. If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them.”

I follow the above observation with one of my own: the dissident anti-demagogic wisdom of Solzhenitsyn is needed now more than ever. Desperately, if not urgently.

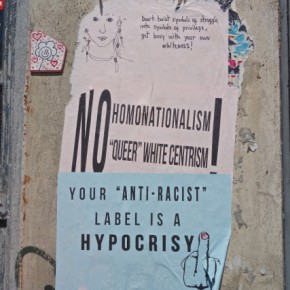

Photographs and screenshots courtesy of the author