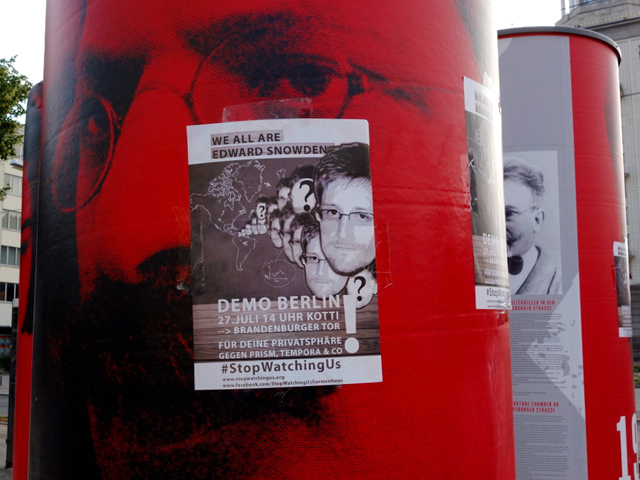

The slogan sounds so good that it’s hard, at first, to register its strangeness: “We are all Edward Snowden.” Consider how many people had access to the same information he did, whether at the NSA or the private contractor where he was employed. But only he made it public. Whatever you think of his motives, Snowden risked everything for them. So why undermine his act of heroism?

While the location of this particular flyer may be an accident, it provides a richly layered answer to this question. Because under that sea of Edward Snowdens lies the unnervingly massive face of Walter Benjamin, who has done more than anyone — most of it posthumously — to make us confront the implications of a culture in which copies reign supreme. In his numerous short pieces on books and toys; in his musings on the rise of window shopping in nineteenth-century Paris; and, above all else, in his endlessly thought-provoking essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin tried to figure out how something could still be special without being singular.

Although he never provided a definitive answer, careful reading of his works reveals his conviction that the passage of time could compensate for mass production’s assault on difference. A child’s tin soldier, velveteen rabbit or Buzz Lightyear action figure might be functionally identical to others of its kind at the outset, but has the potential to acquire a unique character over time, particularly if its history of ownership is richly annotated.

If the commodity form is founded on equivalence, teaching us that every item can be converted into a value suited to exchange, experience is its bête noire, as any parent who has tried to replace a small child’s lost huggy will tell you. Simply put, the one thing that cannot be reproduced, whether in an original work of art or a throwaway consumer good, is what happens after it comes into the world.

The same holds for humans, though to a far greater extent. Whatever our genetic programming, we are indubitably the product of the environment in which we were born and raised. Nutrition, sanitation, education and opportunities for advancement — or the lack of same — all shape our personal development. That’s why the mix of bravery, recklessness and self-regard that made Edward Snowden possible is so rare.

What does it mean, then, to propose that we are all Edward Snowden? Is this a rhetorical strategy to motivate people to nurture their inner rebel? An invitation to identify with his plight, trapped like Tom Hanks in the limbo of an international airport? Or simply a statement of fact written slant, acknowledging that we are all at the mercy of forces intent on depriving us of our liberty and, if we fail to submit, our lives?

At the demonstration this flyer was advertising, participants carried a range of signs. Many favored an image of Angela Merkel, in the style of the iconic “Hope” poster from Barack Obama’s 2008 Presidential campaign, but with the word “Stasi” emblazoned beneath. Others rocked variants on the Obama-with-headphones graphic that has been circulating widely on the internet since Snowden entered the news cycle, the wittiest of which featured the slogan “Yes We Scan.” Plenty of handmade placards communicated the message that their bearers did not require supervision. The overall impression was of exaggerated individuality, like a low-key German take on Burning Man.

But one sign turned this celebration of personal liberty on its head, tarring everyone with the label “terrorist”. This is the ironic flip side of “We are all Edward Snowden,” conveying the hard truth that those of us who play by the rules imposed from above, like his co-workers at Booz Allen, are rewarded for their loyalty by being shoved into the ever-expanding pool of potential security risks.

Following through on this logic, we might conclude that the only sane response to a world in which the government treats everyone like terrorists is for everyone to treat the government like Edward Snowden did.

This formulation distantly echoes Walter Benjamin’s epilogue to “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” — composed in exile, during the mid-1930s — in which he argues that humanity’s “self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.”

For Benjamin, this politicization of art demanded, first and foremost, that it become a mass phenomenon in which people would not only consume the products of the culture industry, but actively contribute to their creation. He insisted upon “modern man’s legitimate claim to being reproduced,” to be multiplied and dispersed in copies of some form or other.

The situation in which we find ourselves today presents a different conundrum. Whereas once it was only a favored few who had the opportunity to be recorded and distributed, now everyone is at risk of receiving this star treatment. Edward Snowden may be the celebrity of the moment, elevated in the mainstream media to the status of a best-selling musician or movie actor, but the rapid proliferation of his image is merely the public shadow of what has been happening in everyone’s private life.

In a world where we are all potential actors in the state’s paranoid fantasies, the challenge is not simply to win recognition, but to put it to good use. If our data doubles are going to circulate regardless of what we do, our best way to preserve a semblance of privacy, paradoxically, might be to overshare.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.