Blaming women for rape? Bollywood actresses talking smack are an obvious satire. The sarcastic video called It’s Your Fault, by comedy troupe All India Bakchod, has won praise, as well as criticism, including from progressives, normally skeptical of English-language productions. For foreigners, it’s a great introduction to how seriously Indians are taking the sex crimes epidemic sweeping their country.

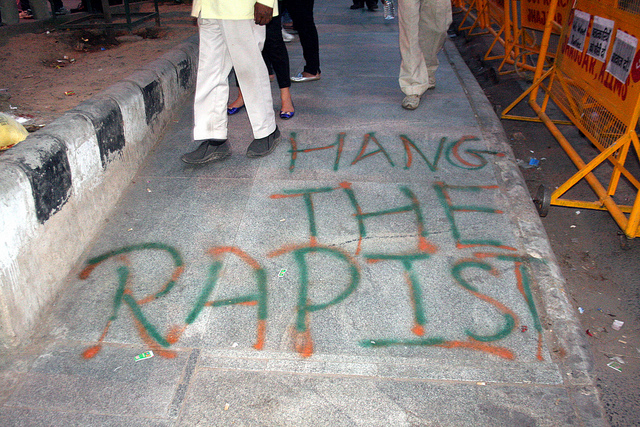

Such discussions are a result of events last December, when a 23-year-old medical student died after a brutal gang rape on a bus in New Delhi (sometimes called India’s “rape capital” by local activists.) The case triggered an uproar, which led to widespread protests and a demand that authorities finally tackle the problem. Many state efforts, such as a proposed name-and-shame database, unfortunately do not go far enough. This is almost inevitable when status-quo institutions are tasked with dealing with an issue that arises from wider problems in Indian society.

It’s crucial to understand that the level of gender violence in India is the result of multiple social failures, both in the country, and on the wider subcontinent. While it is impossible to discuss every factor in depth, we can be sure of several things: The sexual assault crisis is, in fact, a collection of different crises. As such, it requires a discussion of police violence, of family violence, conservative discourses about Westernization, and the continued fallout of both imperialism, not to mention the economy.

Let’s start with law enforcement. There are far too few female police officers in India. Mangai Natarajan has argued that this has been a historic problem. The United Nations estimated in 2000 that only 2.2% of the Indian police force was female, which increased to 3.5% in 2003. This increase fluctuated wildly based on location , but remained marginal in most cases. In New Delhi, the center of national discussions about sexual violence, only 7% of officers are women.

There is also a labor divide among the officers themselves, many of whom are given routine and unimportant posts. According to the Times of India, these posts are almost exclusively inside police stations, with many being assigned to help desks, logistical duties, or as private officers to upper-class families. Almost none are assigned to regular street patrols. Recent recruitment efforts have not changed this core workplace problem.

As in the West, women are much more likely to report sex crimes if female police officers are readily available. They are also much more likely to feel as though they are being heard sympathetically. The absence of female officers has an immediate effect on all levels of how sexual assault is handled by Indian police departments.

It’s Your Fault contains a segment in which a battered actress reports sexual assault to a male police officer, who responds by demeaning and belittling her. This is an extremely common experience for survivors of sexual assault in India today, and South Asia more broadly. Rather than being a safeguard of public safety, the police force is reduced to a beacon of public shaming and half-hearted procedures that go nowhere (India’s conviction rate in rape cases is about 26 percent, and the Indian court system is notoriously lethargic.)

While the additional recruitment of female officers won’t magically solve the problem, it would certainly be beneficial if instituted as part of a wider push for Indian police to better relate to communities under their jurisdiction (rather than elites, as argued by the Brookings Institute,) in this case with matters of sexual violence.

Obviously, this could only be done with a certain degree of imagination. The question that needs to be asked in general, and particularly in certain contexts, is whether or not state violence is the best solution to problems of sexual violence.

For instance, would rural populations skeptical of any type of law enforcement be most effectively disciplined by police? Or would alternate approaches be necessary, such as greater cooperation between security officials and local communities? Are there other methods that can work? What is important is that state institutions accept the possibility that, for example, sending more sex offenders to prison will not actually solve the problem of rape.

This is even more crucial when we consider that the decline in public safety which makes many rapes (such as the daylight gang rape last December) possible may be a consequence of current policing. New forms of regulation may become necessary that critically reshape law enforcement policies, in order that they inhibit the sense of freedom that would-be rapists feel, to prey upon women publicly, in the open.

When discussing gender violence, it is also important to touch on the setting for India’s current sex crimes crisis. These range from talk of individual morality, to larger problems with violence in South Asian families.

Individually, there is a continued trend in South Asia of pinning a woman’s likelihood to experience sexual assault on how ‘modern’ or cosmopolitan she is. This has been observed to an absurd degree in India, with village councils blaming everything from visiting the bazaar, to talking on cell phones, and even eating chow mein noodles, for rape in the country.

Arguments such as these are derived from a belief, articulated by Hindu nationalist groups such as Rashriya Swayamsevak Sangh, that “Western ideals” increase the likelihood of sex crimes. Sexuality that does not conform to traditional models becomes blamed for assaults due to an ill-defined Western decadence. Indians, and South Asians broadly, who subscribe to this narrative, argue that cities like New Delhi are hotbeds of sexual violence because of their Western toxification.

Some nationalists even argue that rural areas are free of rape due to their closer propagation of Indian values (rather than it simply going unreported.) Such arguments are mind-blowing, when one remembers that current “Indian values” are regarded as such because they were mainly circulated through Anglo-imperial rule in the first place. The British Raj marked an intersection between Victorian standards of chastity and South Asian culture, which curiously came to regard one of its closest ideological parents as an enemy for allegedly reveling in behaviors that it also despises.

As in those condemned Western societies, one of the main sources of sexual violence is argued to be provocative clothing. Readers will likely recognize this viewpoint, as it has become a part of mainstream global culture. Rape is argued to occur because the woman has dressed in too tantalizing a manner for the rapist to overcome the commands of his male urges.

Many articles written on this topic have quoted a disturbing, if out of date, 1996 survey in which 68% of Indian judges who were respondents said that provocative clothing is an invitation to rape. Legislators have argued similar points in the past, with one official in Rajasthan pressing for skirts to be banned from private school wardrobes.

It’s All Your Fault pokes fun at these positions as well, by articulating two important points. One is that the rape of “modestly dressed women” in South Asia, such as those who wear burqas in Northwest Pakistan, cannot be explained with such an analysis. Another is that the prescriptive aspects of these beliefs, which include proposals like women restricting themselves to going out during daylight hours, have always been more about restricting female presence in public.

This is particularly true when we consider that patronizing arguments about protecting a woman’s safety have always been a part of the rationale for keeping women at home. Ultimately, attacks on female cosmopolitanism are on women defying traditional standards of family life, which are assigned a falsely anti-rape veneer.

They’ve also led to invented situations of “compromise” that create new situations of sexual torture. For example, many cases of rape have led to invented solutions by which survivors are forced to marry their attackers, appeasing both community standards and family reputations. In other cases, marriage prospects are affected, as being targeted for sexual assault is taken as an indication that the survivor is too morally degenerate to be a “proper” wife. It isn’t hard to understand why so many survivors stay silent, especially in rural areas.

Of course, that doesn’t fully tackle the paradox of assigning the family an anti-rape halo, which directly contradicts the violent realities of South Asian domestic life. Rape is extraordinarily high among married couples on the subcontinent, though it is difficult to find reliable statistics. Views on domestic violence, though, are easier to document. A 2012 report by UNICEF found that, in India, 53 percent of adolescent women, and 57 percent of adolescent men, believed that a husband is justified in beating his wife. These statistics were echoed in neighboring countries, and shockingly reached 88 percent and 80 percent respectively for Nepalese men and women.

Individual South Asian countries have their own unique flares on domestic violence, such as with my native Pakistan and its widely publicized honor killings. But the evidence is clear. Contrary to what nationalist groups believe about South Asian family values, spousal abuse is common. The result is obvious: in India alone, about 37% of women have experienced some form of abuse by their husbands. Children internalize this violence, and it continues.

But how does such a violent ethos come about, exactly? It’s Your Fault doesn’t offer any clues. I find the 1987 Ketan Mehta film Mirch Masala to be a better media reference. The movie revolves around the siege of a mirch factory by a subedar (colonial tax collector) who wishes to rape the protagonist Sonbai, who has sought refuge with the all-female workers. The Muslim gatekeeper Abu Mian chastises the village’s men near the end of the movie, scolding them for dominating their wives at home, but not having the courage to stand up to the subedar.

This scene is well-written and acted because of how succinctly it articulates one of the main reasons that the South Asian family has become so violent. Market-driven societies, and imperial settings such as the British Raj, are built on ritualis of bloodshed and humiliation. This violence is seen in a number of ways, whether through endless toil in wage labor, or the feelings of emasculation that arise from a lack of control, or numerous other factors. Part of the reason that this despair was made possible is because dominated men were allowed the ability to become themselves dominant in their homes.

And in addition, economic disenfranchisement is directly linked to South Asian gender violence. From the outright femicide of girls’ fetuses, which requires life-and-death considerations of children as a source of labor and capital power, to dowry avoidance in poor families, and the overall difficulty that women have in obtaining work (which also means the ability to leave abusive situations,) all the signs are there.

The question is what’s the best way to move forward. I think that current campaigns, including snarky videos, like those of All India Bakchod are extremely helpful. After all, the best place to spread new ideas is through mass media. Particularly those tasked with entertainment, exactly in the same ways that Western comedies have always worked. Take MASH, for example, and the way it used the Korean conflict to criticize the war in Vietnam, while it was happening. The only problem is with accessibility, particularly since English-language videos cannot be viewed or understood by many Indians.

However, it’s also important to have explicit discussions of social problems, that don’t have to resort to humor in order to get the same point across. The last scenes of Mirch Masala feature both dystopian and utopian meditations on this concept. Fearful men and women effectively join forces with those who support the subedar, leading to a chorus of voices and actions that constitute rape culture. However, there are also many aspects in which disenfranchised characters, including Abu Mian, a Muslim man, come together over Sonbai’s cause, and stand in solidarity with one another. For them, an injustice sanctioned by those in power is still an injustice, and must be opposed by the entire community.

Ultimately, the film ends when the factory’s women take matters into their own hands, and blind the subedar with an explosion of red mirch powder. The socialist connotations of this scene are obvious, and plead for wider discussions about power in which all South Asians, who are both elite and oppressed, can participate.

Judging by the trajectory of Indian feminist movements thus far, the world may see those discussions come into fruition sooner rather than later.

Photographs courtesy of Ramesh Lalwani. Published under a Creative Commons License.