It wasn’t until I was stretching as far as I could towards the ceiling, my hand inching towards the smoke detector, that I realized how high up I was. For many people, standing on a ladder, twelve feet above the ground, is no big deal. But for me, the boy who had almost failed out of Cub Scouts for not being able to climb half that high, it surely was. Not the height itself, so much, as the fact that I hadn’t given it a moment’s thought.

We’d been living next door to my wife’s parents for a couple years. Although an extraordinarily competent man in his younger days, my father-in-law was getting too unsteady on his feet to do some of the more arduous household chores. I knew that was part of the reason he had wanted to move down to Tucson with us. But I also knew that my wife was more than capable of helping him out and a hell of a lot more capable than I was.

That’s why it surprised me when, while I was over to watch a football game one Saturday afternoon, he asked me to replace the batteries in his house’s smoke detectors. As I was walking home to retrieve the ladder from our garage — we basically lived next door to them, though separated by a catchment basin for storm water — it did cross my mind that I could ask my wife to help. But that seemed silly in this instance, since I was six inches taller than her and clearly a better candidate to cope with the house’s high ceilings. Rather than lose face, then, I dutifully brought the ladder back and got to work.

Plenty of intellectuals I’ve met over the years grew up in families where it was taken for granted that you pay someone to handle burdensome tasks around the house. But my situation was different. I didn’t come from a wealthy background where such conveniences were de rigeur. My father spent much of his free time maintaining our home and garden, resorting to professional assistance only when it was absolutely necessary. For whatever motive, though, he never encouraged me to help him out. On the contrary, on those occasions when I did express interest in learning how to do something, he would typically become very agitated and worry aloud that I would do more harm than good.

Maybe that had to due with his experience as rocket scientist, where the slightest miscalculation can lead to disaster. Or maybe he was mirroring the anxieties of his own father, though I know he had worked after school in the family business, a camera shop in Flushing. Whatever the explanation, his approach to parenting was as far from “hands-on” as it’s possible to me. That’s no doubt the reason why my mother regularly expressed a desire that her two children grow up to be a plumber or an electrician. Yet this proved to be more wishful thinking, with a note of irony, than a serious attempt to encourage my sister and me in the practical arts.

Sometimes, when people ask why I pursued a career in teaching the humanities, I tell them that words were the only thing I was allowed to touch. I make sure to have a smile on my face when I make this confession and inflect it so that it comes off as a clever exaggeration. But it’s actually an accurate assessment of my predicament, afraid to do so many things because I never had the chance to try them in my youth. While getting a doctorate in English may not seem like taking the path of least resistance, in my case I had a nagging suspicion that it was.

Although I periodically longed for the sense of accomplishment that I’d experienced during those childhood forays into arts and crafts that my father didn’t interfere with, such as building model airplanes, I had reconciled myself to mechanical helplessness by the time I started college. If something needed fixing, I would simply wait around for my roommates to deal with the problem. Embarrassing as it may sound, I was actually relieved when I realized that my second undergraduate girlfriend, who would later become my wife, was the sort of person who would rather do things herself than wait for my assistance.

Back when I was first getting to know my father-in-law, in the early 1990s, my wife’s tales of his fearsomely exacting ways combined with the sheer size of the man — 6’5” and 275 pounds — to intimidate me. Although he only mocked me, gently, for not knowing how to carve the Thanksgiving turkey, a task I always delegated to my wife in spite of his prodding, I suspected that his opinion of me would plummet once he realized just how devoid of handiness I truly was. After all, he had spent over thirty-five years as a union ironworker, working on many of the San Francisco Bay Area’s most significant architectural projects, often hundreds of feet above the ground. By contrast, I couldn’t even climb six feet up in a tree in pursuit of my Wolf badge. So for years I did my best to avoid situations in which my lack of aptitude would be apparent.

What I suddenly understood, high up on that ladder a decade ago, as I leaned down to grab the nine-volt battery my father-in-law was extending upward, was that he had found a way to disable my defenses, motivating me to take on assignments that I would otherwise have shied away from. It was analogous to those swimming lessons they give small children, in which they find themselves immersed in the water before their fears have had time to activate. After having clearly demonstrated that I was up to the task, I couldn’t very well return to insisting that it was beyond me.

From that point onward, I started doing more and more for my father-in-law and, as a consequence, myself. When we first moved into our house, my wife was always the one who would climb the ladder up to the crawlspace to retrieve our boxes of holiday decorations or string lights in the mesquite tree out front. Now I gradually started to share in those tasks, eventually growing confident enough that I would not only spend time on the ladder itself, but would use it to scramble into the tree to reach heights that had previously been inaccessible. By last fall, I was comfortable enough to balance on branches ten feet off the ground, using an extensible pruning saw to trim smaller ones another fifteen feet up or, as the holidays rolled around, to loop strands of lights much higher than we’d ever managed to before.

I am fully aware that anyone who spent time climbing trees as a child would not be impressed with this achievement. But it mattered enormously to me, since I had long been the sort of person who assumes that a task is impossible before giving it a try, an attitude powerfully reinforced by a series of personal and professional setbacks that had battered my self-confidence. Knowing that I could manage to do some things on my own, without the advice or assistance of others, went a long way towards preserving my sanity when I was confronted daily by reminders of failure.

Throughout these difficult years, my father-in-law was the person I spent time with when I needed a break from the pressure. Our interactions were highly ritualized, in the way that relations between men tend to be, but always a source of comfort. He would call early in the week to let me know what time a certain football or basketball game would be on. I would show up roughly forty-five minutes late, so that we could fast-forward through the commercials and finish watching the DVR-ed contest in real time. I would usually pour myself a bowl of the Cheetos he made sure to have around for me; sit down to his right, the side of his good ear; and settle in to converse about the action and a lot of other things as well.

He had a tendency, as many older people do, to tell the same stories over and over. But I never tired of hearing them. I especially liked his tales of working on construction projects, since they would both help me both to understand buildings in a new way — I had once dreamed of becoming an architect — and give me insight into how to handle the far more modest duties of a homeowner. In particular, I learned a lot about what not to do in any project, large or small, such as designing with non-standard materials in mind — inevitably, replacements will be needed after the custom parts are no longer readily available — or, worse still, insisting that workers adapt to more precise tolerances than they are accustomed to. The architects for the complex that drove him into early retirement, San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Gardens, had failed to respect these practical guidelines.

We didn’t only talk sports and architecture, of course. He always made it a point to ask how work was treating me, how my parents were doing, what his daughter and granddaughter were up to. And he would inevitably ask me to come over to help with some household chore or other, a request that frequently turned into a discussion of underlying difficulties and what might be done to address them. He loved looking through those catalogues that sell domestic gadgets, eager to find a mechanical solution. He was firmly convinced that most problems should be solved by finding the right tool for the task, not using the “wrong” tool creatively.

Since my own inclination has always been to cobble fixes together from whatever comes to hand, I couldn’t help but think of Claude Levi-Strauss’ book The Savage Mind, in which he makes a distinction between the sort of thinking exemplified by “primitive” peoples and modern science. The former, he argued, were bricoleurs, who made do, often creatively, with whatever odds and ends were readily available to them; the latter, by contrast, are always pushing past the limits of the pre-existent world, inventing new tools instead of repurposing old ones.

At first, the analogy struck me as a little ironic. Had I spent all those years in school to cultivate a “savage” mind? The more time I spent with my father-in-law, however, the more I realized that he was, at bottom, a man of science. He didn’t simply believe in finding the right tool for the job in a literal sense, but intellectually as well. I have never met a more orderly person. Even after spending months in the hospital and rehabilitation facilities, he could still tell me exactly where to go to find the seemingly insignificant item that he suddenly wanted to have by his side. If my own tendency to disorganization made it easier to use whatever I could readily find, instead of what was best suited to a task, his extraordinarily rational approach to everyday life ensured that he could always locate precisely what he needed in a minute or two.

I would be lying if I said that following his example has cured me of my messiness. While I am trying to impose order on my belongings, I have a very long way to go before I come anywhere near his level of organization. Yet the years I spent with him, talking about how to do things and then doing them, did at least teach me to approach specific projects in an orderly way. I may have box after box of papers remaining to be sorted through, but when I need to build or fix something, I am now consistently able to keep that one, small portion of my life neat and tidy.

I could never quite figure out whether my father-in-law’s confidence in my capabilities derived from a conscious attempt to mentor me or was simply the result of his presumption that any man should know how to handle himself around the house. In the end, though, it didn’t matter. Because the longer our interactions went on, the more I became the man he seemed to think I was all along.

When the door handle broke off our old station wagon, I figured out how to fix it without visiting the repair facility that would have charged me at least $75 labor. When our air conditioner started to fail in the middle of summer, I investigated the unit, found an area that was icing up, and cleared away the debris that had led to the problem, an hour’s work that saved us hundreds of dollars at a minimum. Again, none of this is objectively remarkable — millions of men take repairs of this sort for granted — but it was for me.

My favorite experience helping my father-in-law was also the most arduous. Last year, while we were watching a game together, he explained that he needed my help fixing his adjustable bed. At first, I didn’t understand the magnitude of the job. But when I came over to commence it, I was taken aback. Because the bed was no longer elevating properly, he had ordered a new motor. Installing it, however, would require crawling under the bed, which weighed hundreds of pounds, and making the switch in quarters tighter than someone working underneath an automobile would have to contend with.

I was skeptical. Not once, though, did he express the slightest doubt in my abilities. And his confidence in me once again transformed into self-confidence. In the end, I would have to complete the task three separate times. The first motor he had ordered was defective. The second, it turned out, was not identical to the original and therefore didn’t permit the bed to have its full range of motion. After explaining the problem to him in detail, he brought me out to his garage and got out his power sander. “Maybe we can machine the plastic so that it take and fits right. But if we sand it even a little too long, it won’t work.” By “we”, of course, he meant “me”, since his neuropathy had completely robbed him of his fine motor skills by that point.

I was nervous. I had never done anything like this before. And, what is more, I would be using the power sander for an “off label” application, the sort that my father-in-law had assiduously avoided in the past. At the same time, though, it was clear that I had described the problem clearly enough for him to figure out which of the tools in his garage might be up to the task. And he trusted me, both to have identified the problem correctly and to not screw up while solving it.

When I crawled back under the bed for a third time, repositioning the car jack I’d smartly deployed to elevate it just enough to give me room to maneuver, I was no longer anxious. If this motor didn’t work, he could return it for a new one and have me do the job a fourth time. I wasn’t looking forward to a few more hours craning my neck up towards the undercarriage of the bed, but I knew I could do it if I had to.

Luckily, when I tested the bed, the third time did prove to be the proverbial charm. The motor worked beautifully. Seeing my father-in-law putting the bed through its paces, knowing that he would once again be able to sleep comfortably, gave me a feeling of accomplishment like I’d rarely experienced before. I was returning the favor he had done me years before, by believing in my capabilities when I still didn’t believe in them myself.

Less than a month ago, when the months of being away from home had worn him down, but he was still hoping to return some day to the comforts of his own bed and easy chair, he made a request. “See to it that my wife doesn’t do anything stupid. I tell her to ask for your help, but you know how stubborn she is. Would you do me a favor, when you get a chance? The smoke detectors in the house are over a decade old. They need to be changed.”

I assured him that I would take care of it. In the end, that proved to be the last request he made of me, one that seemed especially fitting, considering how I had first helped him a decade before. I’ve never installed a smoke detector before. I know it will require reaching a little higher, for a little longer, than just changing the batteries did. Yet I also know that I will figure out a way to do the job, because he had no doubt that I was up to the task. It’s bound to bring me to tears: of sadness, yes, but also gratitude, because the only reason I’ll be up on that ladder is that he showed me the way.

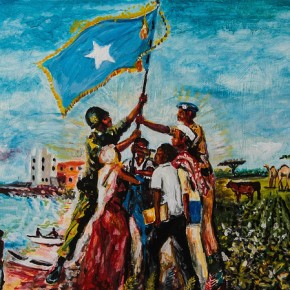

Photographs courtesy of the author