The legend of the Velvet Underground, which is on people’s minds with the death of Lou Reed, has its roots in what “really happened.” According to the legend, the band was never popular during its lifetime, but the few people who loved the Velvets in those early years became important parts of subsequent music culture. Yet there are other ways to interpret the group’s history, ones more specifically personal and less legendary .

The classic Velvet Underground lineup of Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker released four albums between 1967 and 1970. (One way our memories conflict with history: Cale was replaced after two albums, and Tucker didn’t appear on the fourth album, yet both are thought of as “classic VU.”) The first was the most notorious; it reached #171 on the Billboard charts. The second snuck into the Billboard Top 200 at #199. Neither of the final two albums charted, although the third made it to #197 when reissued in 1985.

The legend of the Velvets lies in those chart numbers. As the oft-misquoted Brian Eno explained in a 1982 interview, Lou Reed said to him “that the first Velvet Underground record sold 30,000 copies in the first five years”, to which Eno famously added, “I think everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band!”

Eno’s comment became a part of the legend, which tells us that, through the influence of those 30,000 bands started by fans of The Velvet Underground and Nico, along with Lou Reed’s erratic solo career, The Velvet Underground came to be recognized as a crucially important part of rock history.

Writing for Billboard, Andy Gensler broke down the numbers. As of the end of October, the first album has sold 560,000 units, White Light/White Heat 113,000 units, the self-titled third album 201,000, and Loaded 250,000. Toss in The Best of the Velvet Underground with 308,000, and a handful of other releases (topped by the first cleaning of the table scraps, VU, at 90,000), and we can see that while The Velvet Underground have never sold records at the level of a Jay Z, over time they have had some impact on the charts.

So yes, the legend has its roots in real history. The Velvets were originally ignored, but their influence spread over time. But some of us were too busy with our daily lives to be part of a legend.

In February of 1967, Larry Miller got a gig as a DJ for a foreign-language FM station, KMPX. The Velvet Underground and Nico came out in March. Tom Donahue famously moved in to KMPX, and by the time the Summer of Love was in full swing, KMPX had become a full-time free-form station. I can’t say for a fact that KMPX played that VU album, but where else did I hear it? My brother had a copy, but he had grown up and moved to San Francisco by 1967 (he was the person who told me about KMPX). This is what I can say for what passes for fact in my memory: that first album was popular to me, my friends knew of that album, and, in my narrow, solipsistic mind, anything that was popular with me and my friends was by definition mainstream. Thus, I was unaware that most of the world paid no attention to the Velvets.

Then, in 1970, I moved with my brother to Capitola, California. White Light/White Heat entered our record collection when my brother found it in a garbage bin. I suppose that’s appropriate. The untrustworthy nature of memory pops up here: he doesn’t remember finding the album in the garbage. For some reason, that detail (true or not) has become part of my version of how The Velvet Underground existed in my life.

It was very hard to ignore “Sister Ray.” A few years later, I made friends with a fellow who could recite the entire lyrics to the song; granted, much of it was instrumental, but it was still 17½ minutes long. As we happily sang “I’m searching for my mainline, I said I couldn’t hit it sideways” together, you would have been hard-pressed to convince me that the song was mostly unknown. To my friends and I, “Sister Ray” was part of our mainstream. Even the transgressive elements in the song (and the band) solidified that fact. We knew that many people would be shocked by “Sister Ray,” but that brought us together as a community of transgressors, a mainstream unto ourselves.

In 1974, a few years into Lou Reed’s solo career, he released Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal, which was very popular with the younger steelworkers at the factory where I worked, thanks to the guitar tandem of Dick Wagner and Steve Hunter. That album made #45 on the charts; its follow-up, the largely reviled Sally Can’t Dance, went Top Ten. (Mark Deming at All Music called Sally “the worst studio album of Reed’s career.”) The legend is that Reed’s solo career was erratic at best until at least Street Hassle. There was no room in the legend for a Velvets icon who reached the Top Ten.

I saw Lou Reed in concert for the first time on the Sally Can’t Dance tour. My personal version of The Velvet Underground story was different from the legend. They didn’t become seminal long past the end of their existence; they already were seminal. They weren’t unknown; through Lou Reed, they were in the Top Ten.

I’m not arguing that my personal version is the one that belongs, by itself, in the history books. But I am suggesting that the legend, which over time can ossify into official history, in pretending to represent the overall story, misses the way actual individuals experienced that story. We don’t have legend behind us. All we have is our personal experience. Which is why, whenever an icon passes away, people are compelled to tell their own stories. At least while there is still time, before the legend becomes the fact, we can remind the world that the icon connected with us on a personal level, and there was nothing legendary about it.

If you lived in a legendary time, your experiences, and the foggy memories that result from those experiences, not only sculpt our personal histories, but should add depth to collective histories. Legends do not always get to have the final word.

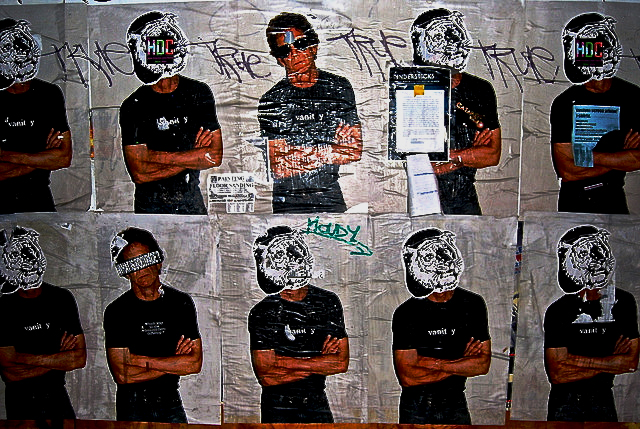

Photographs courtesy of Paul Lowry and River Seal. Published under a Creative Commons license.