Many have noted, with amused or outraged disdain, the contortions with which right-wingers from Dick Cheney to David Cameron are seeking to appropriate a piece of the Madiba magic. Few have as yet noted its converse: icons of the modern left condemning Nelson Mandela for not being socialist enough.

Take Slavoj Zizek, deducing in Sunday’s New York Times that Mandela must have become embittered at his failure to deliver socialism to the black majority. Leave aside for a moment the idea of Mandela being prey to bitterness – an emotion that, as far as I am aware, no-one who knew him ever attributed to him.

Or take Jonathan Cook, who distinguished himself through his insightful, empathic reporting of the conditions of Palestinians in Israel, seeing the ex-ANC leader “forced to become a kind of Princess Diana,” pushed into betraying his people’s aspirations by “a global corporate system of power that he had no hope of challenging alone.”

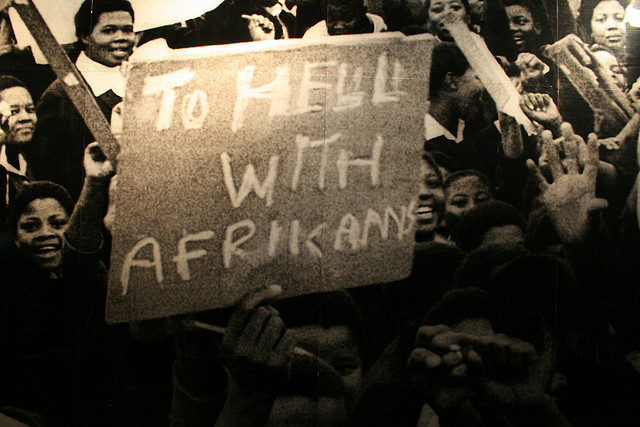

Both writers apparently forgot what actually happened in South Africa at the time that FW De Klerk and Nelson Mandela plotted a way out of the pit into which Apartheid had dug the country. That Zizek seems oblivious to the way in which real people can lash out when the stakes are, literally, the risk of life and death for their entire ethnic group (here, the oppressive white minority) is disappointing. But that Cook, with his vast experience of ethnic conflict, also ignores this crucial point is surprising.

The deal that was thrashed out by the two men was simple: Apartheid would be dismantled, peacefully, on condition of no revenge by the black majority. “No revenge” meant not only no bloodshed, but also no large-scale redistribution.

Had redistribution been a non-negotiable part of Mandela’s demands, Apartheid would not have been dismantled. Simple as that. The whites had the guns, the money and the power, and the very reasonable and justified fear that the overwhelming black majority would, if given half the chance, exact a terrible revenge for the wrongs done to them.

Getting the whites to take that risk – which is what Madiba did – was a spectacular achievement. And the price of that compromise – leaving the white middle classes in their nice houses, in possession of their fat bank accounts – while inarguably distasteful, had to be paid. The alternative was not socialism. It was more apartheid – or genocide.

Nelson Mandela laid the foundations for a society where the former oppressors would feel, extraordinarily enough, that they would not be attacked by their victims, despite the abundant wrong done to them.

This leftist critique also includes the accusation that Mandela tolerated, encouraged even, the growth of a capitalist black elite. It is blaming Mandela for the fact that many of his African National Congress comrades were unable to resist temptation and proceeded to rapidly enrich themselves rather than work for the common good. It forgets that these men wanted revenge. Letting them grow fat is also Mandela’s achievement. The risk of revenge killings – or worse – receded as former guerrillas lost themselves in glittering cars, fast women and champagne – or built new business empires.

Slavoj Zizek and Jonathan Cook are suggesting that Nelson Mandela should have found another way of transitioning away from Apartheid, one that would have introduced equality while maintaining the signal achievement of no bloodshed. They seem in no doubt that had he really applied himself, he could have ensured that South Africa would forevermore be graced by pink unicorns gamboling under glittering rainbows in a pastel landscape.

Very rarely does one man manage to vanquish such an enormous evil through non-violence. It’s so rare because it is so hard. Such efforts demand an exceptional combination of circumstances seized by extraordinary persons.

Thus, it’s reasonable to celebrate. Especially given how rare such breakthroughs are, and the obvious milestones they set. Indeed, Mandela was one of those precious few whose qualities allowed him to make the world an unmistakably better place.

That is an achievement that should not be sullied by a misplaced appropriation of blame for the fact that the country he transformed has not yet become a paradise. Rather, it’s an invitation to take Madiba’s work to the next level, and stamp out social inequality.

Photographs courtesy of Tarouk and United Nations Photo. Published under a Creative Commons license.