If metal has become incoherent, there’s little sign that it is dying. Yet there are two dangers that are beginning to loom large over it. The first is that metal gradually dissipates. The music moves in a thousand different directions, by a thousand different artists. Any sense of it as an overarching idiom, a cultural identity, and a social space is lost.

Metal’s constituent musical characteristics are spread widely throughout music, decoupled from a distinctive sense of metalness, to become one set of musical possibilities among many others. This is the usual fate of musical genres. They don’t usually die; their constituent elements simply become incorporated into one or a number of successor genres. For example, the baroque music of Bach became obsolete by the end of the eighteenth century in that few no works were produced in this style. But you can find its influence in multiple types of music, heavy metal included.

The second danger is that metal becomes a static, ossified music scene, dedicated only to the repetition of earlier sounds. Metal becomes like ‘classical’ music, with a barely changing ‘core’ canon surrounded by avant garde and neo-classical ‘fringes’ where works are still produced, but rarely enter the core. Metal never quite dies, it just repeats itself. Eventually metal will not survive as anything other than a fringe collection of archivists and obsessives. This is the definition of genre death given in a post by Doug Moore on the Invisible Oranges blog in October 2012 : “A genre dies when so few musicians write music that they identify as a part of said genre that its canon ceases to meaningfully expand.”

There is a real dilemma here. If metal continues to innovate, but without an overarching scenic structure, then it risks dissolution,. But if it focuses on protecting its boundaries and distinctiveness, then it risks artistic ossification. Metal’s future depends on picking out a way forward that avoids both of these dangers.

But does it matter if metal has a long-term future? Does metal need to survive in perpetuity? Maybe it’s healthy for scenes and genres to disappear after a while. While many of today’s metalheads would certainly be distressed if metal didn’t survive into their old age, do they really care if there is metal around 100 years after they die?

There are certainly elements of metal we could point to that should have a long-term future. Distorted guitar sounds, tritones, sonic transgression and fellowship are all aspects of metal we might want to preserve. If metal’s future is to repeat itself as it slides into irrelevance, then we might fear for the future of these things. If metal’s future is to dissolve, we could see metal preserved in its constituent parts. The question then becomes if it is desirable for metal survive as an identifiable, overarching framework.

It doesn’t necessarily matter what happens to metal, so long as those who are emotionally committed to it are provided for. If no one wants metal to continue, then there is no need for it to continue. Metal should survive as long as people want it to survive. And metal’s survival can become even more desirable if the processes that will ensure its survival grapple with the significant challenges of our age. In order to survive into the future, metal needs to face to this new age of abundance. No music scene has yet done this. Metal’s future thus depends on blazing a new trail towards an as yet unimagined cultural space and time, where it is no longer as ubiquitous as it is today.

So what is to be done?

A response to the crisis requires the enhancement of metal’s ability to look to the future. This involves an enhancement of the metal’s capacity for reflexivity. Reflexivity is the ability to ground our actions on an assessment of their likely consequences, based on an awareness of the past. Crucially, while it is the precondition for everyday interaction – and therefore something we are all capable of – reflexivity is also something that can be developed and enhanced.

As I argued in my book Extreme Metal, metal scenes have developed an odd kind of reflexivity. While scene members demonstrate a considerable sophistication in reflexively managing the complex work of scene-making, it is a self-consciousness that is sharply limited. Indeed, it is often turned against itself in the strange phenomenon of ‘reflexive anti-reflexivity’ in which scene members demonstrate considerable sophistication in appearing incredibly unsophisticated. The end result is that in metal scenes, certain questions, issues and challenges are often ruled out of bounds. While the self-awareness of metal has certainly been boosted in recent years with the increasing prominence of women and other metal minorities, it still remains a culture that is often resistant to a fuller embrace of its increasingly diverse identity.

Metal’s limited reflexivity may have served it well in the past, but it has left it ill-equipped to face the challenges that it faces now and in the future. In particular, there is little discussion in the metal world of the challenge of developing resilience. Metal is part of a fast-changing world in which no institution or cultural practice can never be guaranteed to endure. Metal’s complex institutional and aesthetic archipelago was built up during times that were different to the present. While it may have proved resilient so far, that does not mean that it will continue to be so indefinitely. Metal scene members may be exceptionally adept in maintaining and navigating metal’s communal infrastructure, but they don’t always have the breadth of vision to understand the wider context of their scenes. Indeed, as in any scene (take hardcore punk, for example,) deep involvement in metal can actually foster the illusion that life can be lived through metal alone.

Another limitation to metal’s reflexivity is in regard to metal’s memory. That isn’t to say that metal isn’t conscious of its history. Deep knowledge of metal’s manifold artists and sub-genres is highly prized in metal, and so is loyalty to metal artists over time. But metal’s memory has its blind spots. Canons are always based on exclusion and on the smoothing out of historical complexity. One example is the exclusion of black artists and black music from metal’s collective memory, in which a figure as pivotal as Jimi Hendrix can be totally marginalised. Another example is the close interplay between extreme metal and indie rock in the late 1980s – something I was closely involved in but which is often forgotten by both metallers and indie fans. Metal will be in a better place to face the challenges of the future if it is more open about the complexities of its past.

Reflexivity involves facing the future through an unflinching looks at the past and the present. It is this future-orientation that is most absent in metal. In fact, this is part of a more general absence in thinking about popular music, even in scholarly studies. Attempts to speculate on the future are largely confined to understanding the short to medium term impact of changes in music technology and the music business. There has been little attempt to predict the longer term aesthetic, social and cultural shifts that will mark popular music in the future.

In some ways, this ignoring of the future is ironic, given that post-war popular music has been at the forefront of social change. Indeed, as Jacques Atalli has influentially argued, music provides both a harbinger and a stimulus to the shifts in socio-cultural tectonic plates. It is hard to imagine the manifold changes that occurred in the West in the 1960s apart from the dramatic changes in the place and the nature of popular music that both catalysed them and signalled their coming. Some popular musicians have been actively interested in the future as a theme in their work; in metal we can think of the obsession with nuclear war and apocalyptic destruction that marked thrash metal in the late 1980s. Yet post-war musicians have rarely made a conscious, reflexive attempt to grapple with the long-term future of music itself. Even if artists have often sought to push forward the possibilities of music through exploiting new technology, it is much rarer to find artists speculating on what the place of music will be in 50, 100, 1000 years’ time.

‘Futuristic’ music of the Kraftwerk-kind is tinged with a sense of self-parody, a consciousness that nothing dates faster than visions of the future. Futuristic music rarely tries to imagine new possibilities for how music might be embedded within society. No one either predicted in advanced the ground-breaking innovations that the Beatles, Slayer or Kraftwerk made. This blindness to the future has actually served post-war popular music very well. The shock that new developments like punk or black metal caused is part of their power and pleasure. Yet while future-blindness may have served popular music very well in the past, it’s not serving it well in a period of crisis.

How could the metal scene develop a more sustained and profound reflexivity? Metal critics and metal scholars have a crucial role to play here. Metal has a contradictory relationship to music criticism and the written word more generally. On the one hand, metal is a highly literate culture, perhaps more so than any pop music genre. Literary references abound in metal song lyrics. On the other hand, metal criticism – at least the metal criticism that occurs within metal scenes themselves – has often been simplistic. For much of the 1980s and 1990s, metal fanzines and magazines were usually uncritically celebratory or even purely utilitarian, tracking the latest releases and offering a platform to metal bands. Metal criticism has become more diverse in recent years. The sardonic tone of black metal fanzines played an important role here, as did the proliferation of online writing outlets and the growth of metal studies. Nonetheless, there is still resistance to more complex critical writing on metal.

While the development of metal studies has been welcomed in many metal quarters, there is also significant pushback from those who see metal as ideally instinctual and anti-intellectual. This isn’t just the case in metal. Within most music scenes there is a widely-felt desire for them to follow their own course, to not be guided or analysed. Music scenes are not centrally planned or run by committee. Music scenes don’t attract think tanks and policy wonks to plan the course they should take. This instinctual approach is what makes music scenes so exciting – you never know what they are going to do next. But this is also what makes them vulnerable as there are some challenges that cannot easily be faced without some kind of conscious effort. The crisis of abundance is precisely this kind of challenge.

Metal critics and scholars can play an essential role in helping metal to face and adapt to the crisis. In order to do this, it is necessary to rethink what music criticism means in an age of abundance. In a piece published 1969, the American rock critic Robert Christgau reflected on the peculiar status of the critic:

“Unless you are very rich and very freaky, your relationship to rock is nothing like mine. By profession, I am surfeited with records and live music. Virtually every rock LP produced in this country is mailed to me automatically, and I’m asked to go to more concerts than I can bear. I own about 90 percent of the worthwhile rock albums released since the start of the Beatles era, and occasionally I play every one of them.”

Rock critics, and metal critics too, used to owe their status to their access to and mastery of a huge number of music releases. ‘Regular’ individuals who were not sent review copies found it very difficult to attain the knowledge that critics had. This access meant that critics were able to define genres and contextualise artists within them. While in metal, tape trading meant that non-critics were able, with difficulty, to attain this vast knowledge, most metal fans were still dependent on metal publications and their writers in order to make sense of the genre.

Today, the unique status of critics has been eroded. Not only have outlets for criticism proliferated, but it is easier than ever for anyone to develop what was once a hard to achieve familiarity with the breadth and depth of a genre. Yet, the flood of releases and the breadth of metal means that even the most assiduous critic cannot keep track of ‘everything’ anymore. Not only are the roles of critic and fan becoming ever more blurred, but both are equally adrift in the sea of musical abundance. Metal criticism, like other forms of rock criticism, is not redundant as there is still a need to critics to pick out pathways through the metal forest. At the same time, in an age of abundance, criticism is also a contributor to the crisis in that discourse on metal, like metal music itself, is so accessible and available that it itself is a part of the profuseness that threatens metal’s identity and coherence.

Metal criticism can help metal to confront the challenges it faces in an age of abundance by doing something that is not ordinarily done in metal scenes. That is, not just commenting on music as it is released, but imagining music that could be made; not just trying to understand the metal scene as it is and as it was, but actively imagining what it could be. Critics rarely ‘lead’ innovation. Developments in popular music are led by musicians and those who run scenic institutions. But there is no reason that this situation should endure indefinitely. When metal critics are communally engaged in the metal world – which they usually are – they are in a position to make strategic interventions in metal discourse designed to open up possibilities for new kinds of aesthetics, practices and sounds. Why should metal musicians be the only ones working on what metal be in the future? Why shouldn’t critics set musicians challenges to make music that doesn’t currently exist?

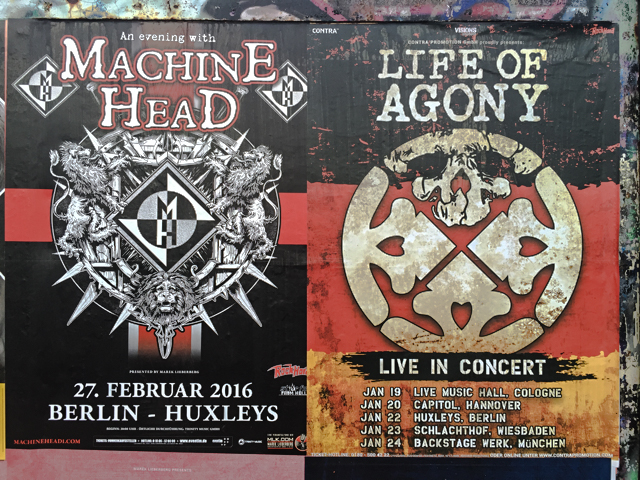

Part four in a series. Photographs courtesy of Michael I070, Geoffrey, and Paul Bridgestock. Published under a Creative Commons license.