76 people had been killed during a Syrian assault on Aleppo. 28 of the casualties were said to be children. Despite the high death toll, I was pessimistic that the West would take notice. “It seems few care about Syrian lives, unless they’re killed by a chemical weapon,” I angrily tweeted. My despair reflected a decline in public interest in Syria’s civil war. Yes, the attack made the news, but it elicited no outcry. The Syrian conflict has gone on so long, and has been so horrifying, that it’s now just a disturbing buzz. The media still takes note, but we’ve moved on.

One person responded to my distressful message though, tweeting that people do care, but the rebels are too radical to merit support. What is there to do, they asked? This question illustrates the problem. Is there no other decisive action to be taken than backing one warring party or the other? Is it impossible to assemble a code of international principles that allows for the defense of human rights and protection of civilians in a direct way, without taking sides in a conflict? Right now, there isn’t. We need to make new options.

Too many people are comfortable with standing by, as Syria is engulfed in flames. The strength of this disposition is based on the lessons of Iraq, and how badly that intervention changed the Middle East. As Adam Shatz argues in the London Review of Books, it was Iraq that set the stage for the current events in Syria. Indeed, it would be hard to imagine the Syrian crisis without its precedent. But, can the US and Europe simply leave the region to live with the after-effects of our mistake? Not everything is Bush and Blair’s fault. Still, we bear significant responsibility for the Syrian crisis. Enough, it seems, to warrant more constructive engagement than at present.

The West must start from the basic principle of not making things worse. We surely have done enough of that already. But it is too easy to take that idea and use it as an excuse to do nothing. We should be finding a way to act positively and productively, albeit carefully.

So what should be done? How can the paralysis be broken? The Syrian conflict illustrates the difficulties in averting a regional conflict. The US, Europe, China, Russia and many other states all have a stake in resolving it. But democracy cannot be instituted at gunpoint. It is often the case that the warring parties are highly sectarian, don’t necessarily represent the popular will on either side, and don’t seem like reliable allies for the great powers.

In Syria, the distaste many feel for the rebels has combined with conflicting great power interests to present a serious obstacle to international action. There is also relative indifference to the loss of non-combatant life which became apparent when the international community found itself able to act with regard to the use of chemical weapons, but continues to be stymied with regard to the broader conflict, which has claimed over one hundred times more lives and created millions of refugees. This situation is not tolerable, and indeed it is quite dangerous.

The notion of widespread “pro-Western” or even pro-China or pro-Russian militias rising up to combat existing Arab dictators or al-Qaeda forces is entirely unrealistic. Such scenarios are neither realistic, nor will they suffice as solutions. Most people, wherever they live, are primarily interested in a more prosperous and just society for their children, and wish to live in greater freedom and security. Such goals are often not represented by sectarian groups. And, as we see in Syria, outside interests often conflict, in their sponsorship of rebel organizations.

The way forward is not to take sides. This thinking is outdated, and has been proven time and again to lead to greater problems in the long term, even in the cases where interference works in the short term, which is far from the norm. Rather, it will be necessary to create a forum where heads of state can work together, with popular representatives, including both militias and civil society or religious organizations, to resolve local conflicts.

Much of the problem is the absence of an appropriate forum for action. In Geneva, there was success in assembling a forum where Iran and the P5+1 could come together and enter negotiations. However, such a forum for Syria has proven much more difficult to arrange. This has been due, again, both to an understandable unwillingness of some Syrian parties to sit down with the Assad regime, as well as questions about how Russia could both pursue a resolution and maintain its own interests, and what sort of participation, if any, Iran might have.

Can the United Nations spawn a new forum that can address such conflicts? I believe that it can, although building one would take far too long to address the Syrian conflict. Indeed, with the mushrooming of conflict in Syria, which is now featuring not only the rebellion against Assad, but escalating conflict between various rebel groups, it may well be too late to do anything productive. But it never should have gotten to this point, and would certainly not have if there had been a mechanism for the international community to protect Syrian civilians at the outset.

Our goal needs to be to set up a system whereby the international community would not be stymied in the future. The guiding principle must be an end to international excuses for sitting back and watching similar tragedies occur in Syria, in Rwanda, and Bosnia. There is sufficient historical incentive to move forward.

The way to deal with such conflicts is to have something akin to regional security councils. There can be Middle Eastern, Latin American, European, and other such councils. Each council would include a representative from each of the countries in the region, plus the five permanent UNSC members, in order to ensure a global political process. The forums would then exist to address regional conflicts among the players, but also on a global level.

A set of standards could be drawn up to define additional representatives. Permanent representatives to those councils could be representatives of recognized NGOs that represent significant sectors of civil society and movement leaders, possibly including militias. While this may mean granting legitimacy to designated terrorists, the councils would operate on the basis of dialogue to resolve conflict, which cannot be achieved without bringing all parties to the table.

Regional security councils would also be empowered to assemble both peacemaking and peacekeeping forces, which could act when a government either loses its control of the country or acts in such gross violation of international law by attacking its own citizens. One such force would exist to protect civilians in times of conflict, and the other would act as a transitional force to maintain security while governments get rebuilt. By having full regional representation, as well as significant international representation, there would be a broad enough political process to avoid any outside interests asserting dominance.

Regional security councils would thus have the power to act. It would also mirror the UN Security Council by having broad membership. The UNSC which would have to approve any actionable decisions by the Regionals. But the Regionals themselves would be composed of countries with equal representation in that forum. No country would have veto power.

Once a Regional SC established legitimacy, a dialogue forum could be assembled to address crises such as that taking place in Syria. Diplomats at the deputy level could negotiate and mediate. Rebels would be invited to participate. If the council idea had gained popular legitimacy, they would feel compelled to respect it, even if the regime it was fighting was at the table as well. Negotiations could address a political transition that was acceptable to all, and satisfied outside concerns felt by states like Saudi Arabia, Iran and Russia.

Ultimately, such fora can work for the very simple reason that most countries with a stake in any conflict will have a strong interest in peacefully resolving it. Enough would have such a preference that the more unusual case where one or a few states might prefer a battle to the end (probably because they believe their side would emerge victorious) would feel great political pressure to negotiate, despite their own preferred strategies.

In the Syrian case, a country like Saudi Arabia currently has no better option to pursue its regional interests than by backing a violent militia and escalating the conflict, out of the conviction that a military victory for Saudi backed forces was a possibility. In such an instance, a regional security council would facilitate pressure on Saudi Arabia to change course, and leverage its influence on Sunni combatants to secure a negotiated, peaceful outcome.

The Saudis won’t like that. Depending on who is in the White House, the US may not either. But in the end, the immediate benefits would be too great to resist. In the long run, popular pressures would inevitably sustain such structures, as everyone would stand to benefit from them. Even for forces that loathe democracy and the rule of law, negotiations and dialogue are a better option than the risk of massive regional conflagration.

This is an idea whose time has not only come, but has been here for a long time. The current international system is obviously inadequate to address the growing sectarian, civil, and asymmetrical conflicts that are seen not only in the Middle East, but also in Africa, Latin America, the Caucasus region, and, not so long ago, the Balkans.

Again, the UN Security Council’s failings are instructive. The veto power held by its five member states stymies progress The lack of even a forum dedicated to resolving particular regional conflicts is another obstacle. But most of all, the notion that the choices are limited to high-level diplomacy and humanitarian aid, or taking sides, has to be overcome. There needs to be a third way. The alternative is more Syrias to come.

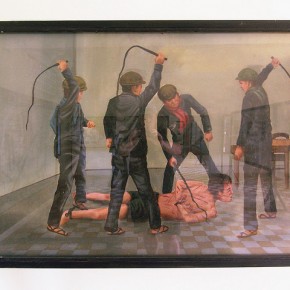

Photographs courtesy of the Syrian Revolution Memory Project, Gwydion Williams, and Sasha Kimel. Published under a Creative Commons license.