The Wall Street Journal has published a promotional excerpt from Robert M. Gates’ memoirs, Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary of War. It’s a much needed glimpse into the wartime thinking of the Obama Administration, particularly its similarities to its predecessor, the Bush Administration. Some of Gates’ opinions, particularly in praise of the Afghan troop surge, are frustrating. However, this is to be expected. Retired public figures mainly write memoirs to clarify their legacies, as President Bush did in Decision Points. Gates is defending his most famous work, which leads to factual omissions, and exaggerations.

The excerpt is still excellent though. The former Defense Secretary has some very strong feelings on how it was to conduct his job, and not all of them translated into policy. Consider his opposition to long-distance counterterrorism:

But if I had learned one useful lesson from Iraq, it was that progress depended on security for much of the population. This was why I could not sign onto Vice President Biden’s preferred strategy of reducing our presence in Afghanistan to rely on counterterrorist strikes from afar: “Whac-A-Mole” hits on Taliban leaders weren’t a long-term strategy.

And yet, despite Gates successfully pushing for an alternate plan of a troop surge, it appears that “Whac-A-Mole” is the order of the day (it’s an apt description of the drone strikes program as any.) It appears confusing until you recall the detail that Gates leaves out: the Afghan troop surge, unlike its Iraqi cousin, was a disaster that led to a dramatic escalation of violence.

Gates is entirely correct to criticize President Obama for placing far too much in “systems analysis, computer models, game theories or doctrines that suggest that war is anything other than tragic, inefficient and uncertain.” These types of policy games are extremely dangerous. War is not a video game.

However, Obama was also at an impasse: “boots on the ground” was discredited by new violence, and so he gave new consideration to “Whac-A-Mole,” a strategy that preserves American lives and minimizes total expenditure while still projecting hard power. The alternative would have meant withdrawing from Afghanistan, which would have risked making President Obama look weak domestically, which Gates alleges was a major concern:

With Obama, however, I joined a new, inexperienced president determined to change course—and equally determined from day one to win re-election. Domestic political considerations would therefore be a factor, though I believe never a decisive one, in virtually every major national security problem we tackled.

There are other interesting comments too. For instance, Gates calls Obama’s White House the most centralized one since Nixon, which is a comparison that’s been made before, too. He also sheds some light on Obama’s cool relationships with both world leaders and military elites, the latter of which is probably born from his personal distaste for armed conflict.

Personally, my favorite is his apt description of the overactive eagerness to go to war that has defined the Obama years:

Today, too many ideologues call for U.S. force as the first option rather than a last resort. On the left, we hear about the “responsibility to protect” civilians to justify military intervention in Libya, Syria, Sudan and elsewhere. On the right, the failure to strike Syria or Iran is deemed an abdication of U.S. leadership. And so the rest of the world sees the U.S. as a militaristic country quick to launch planes, cruise missiles and drones deep into sovereign countries or ungoverned spaces. There are limits to what even the strongest and greatest nation on Earth can do—and not every outrage, act of aggression, oppression or crisis should elicit a U.S. military response.

On point, and unfortunately, it is a trend that will survive the Obama presidency.

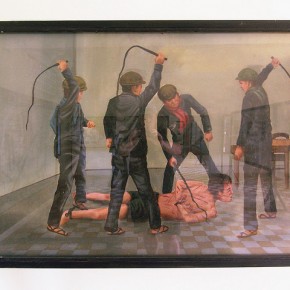

Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Army. Published under a Creative Commons license.