On July 27th, 1983, the Turkish Ambassador’s residence in Lisbon was seized by militants of the Armenian Revolutionary Army, following a failed attempt at storming the embassy. After a standoff with 170 Portuguese riot police, the building was blown up, killing the four ARA fighters inside, one Portuguese policeman and Cahide Mıhçıoğlu, wife of the embassy’s charge d’affaires.

The five Lebanese-Armenian attackers (one of whom was shot dead by a Turkish bodyguard before the siege began) were named as Setrak Ajamian, Ara Kurjulian, Sarkis Abrahamian, Simon Yaniyan and Vache Daglian. All were between 19 and 21 years of age. Buried in Beirut’s Bourj Hammoud Armenian cemetery, they became heroes to many Armenian activists worldwide, and not without some controversy. Of the numerous Armenian militant attacks on Turkish targets from the Esenboga to the Orly airport attacks in 1982 and 1983, that of the ‘Lisbon five’ is still commemorated, in 2014, in the side streets and alleyways of the Armenian capital of Yerevan.

The explanation for this act is hidden in the headache of Armenian politics. Modern Yerevan, largely the brainchild of Soviet Armenian architect Alexander Tamanyan, has ample space for political dissent – at least, expressed on its concrete. So whose stencils and black paint honour the Lisbon five? “Probably some fringe extremist group,” wondered one analyst aloud “though thank God they aim spray cans instead of pistols.”

A repatriate Armenian friend has another theory – the Lisbon 5’s wide presence, if not yet omnipresence, is the work of the Dashnak Party, the sole remainder of the three oldest Armenian political movements currently represented in parliament. The Dashnaks had close associations with the ARA militants, in contrast to their rivals, the more successful (though I use the word with some discomfort) ASALA, the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia. The two organisations shared similar goals, including Turkish recognition of the Armenian genocide and the unification of Western (Turkish) and Eastern (then Soviet) Armenia.

“Militant patriotic” is just one word in Armenian, Razmahayrenasirakan. Often used sarcastically, particularly on the ArmComedy television show, it can refer to a particular brand of traditional Armenian music. Popular Syrian-Armenian singer Karnig Sarkissian – himself prosecuted in 1982 for conspiring to bomb the Turkish consulate in Philadelphia, dedicated a song to the Lisbon Five, to those “brave, shining knights.” “I will die without having seen my motherland,” remarked Ajamian before leaving for Lisbon in the summer of 1983, ‘”but I don’t care. Others will.”

Armenian independence saw subsequent shift in political activity towards the Republic (commonly referred to as the ‘Question’) of Nagorno-Karabakh. Just over thirty years on from the events in Lisbon, retrospectives and analyses of the event appear tentative, if not tenuous. “In this post-9/11 world,” noted Greg Bedian as the Armenian-American Community of Chicago commemorated the 30th anniversary of the Lisbon attack in 2013, “it might be difficult for some to comprehend such an act.”

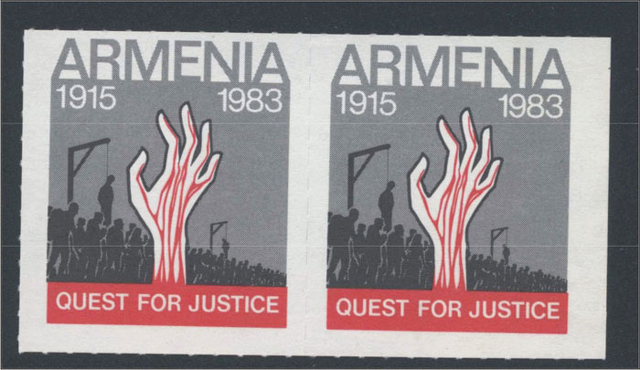

Dashnak activist Dr. Antranig Kasbarian in his feature Lessons from Lisbon observed that by the 1980s, fears arose about whether the Armenian armed struggle had gone too far. Yet the actions of the Lisbon Five, he added, were by no means pointless. “They made Turkey blink,” repoliticising Armenian diaspora communities and prompting further public discussion on the Armenian Genocide. It was, one gathers, a time of frustration and disillusion. A context in which, explains my repatriate friend – partly absolving, partly explaining – romantic, Cold War-era freedom fighters gave a common sense of political purpose for Armenians across the world. “A small nation,” as Milan Kundera once wrote “can disappear, and it knows it.”

“Does anybody seriously believe’ wondered one commenter online ‘that the murder of the wife of the Charge d’Affaires and a Portuguese policeman brings honour to the Armenian people?”Another drew uncomfortable comparisons between the militants in Lisbon and Azerbaijani soldier Rimil Safarov, who murdered sleeping Armenian colleague Gurgen Margarian with an axe at a NATO training seminar in Budapest in 2004. Upon his extradition to Azerbaijan in 2012, Safarov was pardoned by President Ilham Aliev, and comparisons were drawn (particularly in Azerbaijan) with the less publicised pardon of ASALA militant Varoujan Garabedian in 2001. “The times have changed,” noted Dashnak youth leader Meghmik Babakhanian at a 2008 commemoration of the Lisbon Five in Glendale “and so have the means by which we struggle for justice.” To return to the title of Kasbarian’s article, there are still lessons to be learnt from the Lisbon Five.

In 1932, Arthur Koestler described Yerevan as “A kind of Tel Aviv, where the survivors of another martyred nation gathered to construct a new home.” After six months, I am unsettled by quite how familiar, even mundane, the faces of these five ‘martyrs’ have become. Yet the face which stared out of the display cabinet of the gift shop of the Armenian National Gallery was unforeseen, anonymous behind its black balaclava. Amongst rows of hand-painted souvenir figures in national costume hid an armed ASALA militant in fatigues. An Armenian letter F drawn on the balaclava stood for Fedayee (“He who sacrifices himself,”in Arabic.) What an ASALA figurine stood for in a Yerevan gift shop in 2014 was less clear – to me, at least. The cashier picked up the Fedayee and raised both eyebrows. “Do you sell many of these?” I asked, half in jest. “Oh, I’m sure we would,” she replied.”But that’s the last one, and they don’t make them quite as well as they used to.”

Photographs courtesy of Sedrak Mkrtchyan, suhikayeleri.com and the author. Published under a Creative Commons license.