Zia ul-Haq was disgusted by Western culture. Much to the horror of Pakistan’s elites, the late President took his cues from Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, and sought to limit its corrupting influence on the country’s youth. Still, Pakistanis rebelled. Pioneering Punjabi rock band Junoon led the charge.

As Pakistan became more culturally conservative, punk and metal grew in their appeal. Although the subcultures were effectively driven underground by Islamization, they were openly celebrated in urban areas, and Pakistanis spent much of the 1980s obsessed with consuming Western fashion styles and musical genres.

This was especially true if they were rich. Pakistani musical taste is greatly affected by one’s views on secularism, which has always aligned with wealth and status in the country.

The problem facing this wave of Pakistani culture was that it didn’t really have anything “Pakistani” about it. Local music was produced without local influences, and was typically unmemorable. The emphasis was on imitation rather than fusion. Though hipsters have often found Third World adaptations of Western counterculture oftentimes worthy in its own right, parody can only go so far. If you can call it that. Otherwise, it’s just Guns and Roses, in Urdu.

Still, you can understand the impulse. It’s political in its own way. During the Zia era, traditional culture, writ large, was identified with militarism and religious nationalism. It was natural, especially for young people, to rebel by consuming Western products, however apolitical they might be, in their original context. In a Pakistani context, they were rebellious. This remains true today. It was a necessaary preparatory stage, as Pakistanis had to get their heads around what was going on abroad, before they could create their own truly local counterculture.

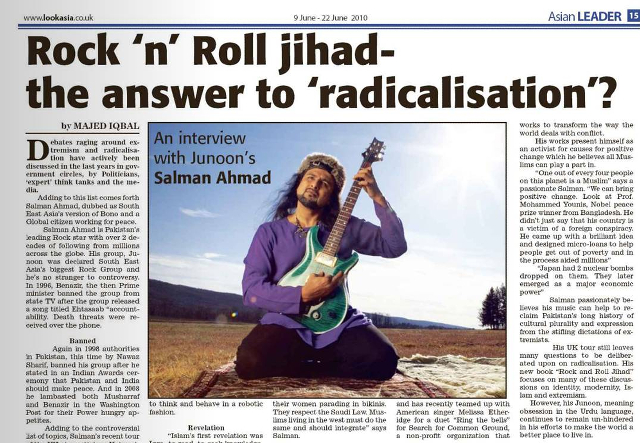

Junoon was the best-known group to emerge from this period. The band released its self-titled debut album in 1991, followed up by the 1993 LP Talaash, which was met with critical acclaim and earned the group a cult following. Their 1996 album Inquilaab, and follow-up recordings, propelled Junoon into the mainstream, where its trademark East-West sound – rock guitars and vocals, mixed with tablas and traditional folk music and qawwalis – connected with a generation of Pakistanis, for whom such cultural hybrids were natural.

The mix of these influences is what led to Pakistani rock journalist and social critic Nadeem Paracha to claim that Junoon had invented a new genre: “sufi rock.” It was a fusion that guitarist Salman Ahmed aspired to ever since seeing a Led Zeppelin show in New York during the 1970s. Younger bands, including the leftist Laal and the Mekaal Hasan Band, followed.

Saeen, from Junoon’s Inquilaab LP, is a great example of the group’s style: although electronic instruments are used, the effect is psychedelic and trance-like, with an emphasis on Sufi religious traditions. Especially with the parts of the chorus that consist of “Allah!” being passionately screamed repeatedly. If the Velvet Underground had been a Pakistani band, it’s not too difficult to imagine them sounding like this. The fact that such songs celebrated Sufism during a period of severe animosity towards the tradition made them even better.

Mixing Asian and Western music wasn’t just a 1960s-style aesthetic exercise for Junoon. The band’s political objectives play a role in their syntheses, too. For instance, the 1993 song Talaash on their second album (of the same name) is an Urdu-language polemic against the politics of Pakistani Islamism. Featuring radio recordings that report the hanging of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto by General Zia ul-Haq, the European-style montage spoke for itself. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif responded by banning the song from state-run television and radio. This would be done again for the music video of Ehtesaab, a massively controversial piece about working class turmoil and servitude, featuring a polo pony eating at an upscale restaurant. It was a scathing indictment of Pakistan’s corrupt political elite, especially the Bhuttos.

Junoon, and many other bands of the era, were writing music that they hoped would galvanize a radical change in perspective. Like other progressive-minded artists, both at home and abroad, they had good reason to believe that the right beat, so to speak, could change the world. In the immediate context of their musical experimentation, they were in fact revolutionaries, effecting, and reflecting, enormous cultural changes within their own community.

However, the band’s political goals were limited by their audience: largely privileged and secular, and from upper-class families in major cities like Lahore. Though commercially successful, Junoon never managed to break out of being a band for elites. Someone else was going to have to build on their breakthroughs, and recreate their politics for a mass audience. That has yet to happen. But that doesn’t mean it couldn’t, or won’t happen in the future,

This isn’t to say that Junoon’s work was for naught. Pakistani rock has always been popular amongst the country’s up-and-coming power brokers, and they have certainly been affected by different cultural sensibilities. However, Pakistani politics rests on the decisions of its younger working-class population, which is deeply religious, and in many cases has been pushed by Islamization to hate groups like Junoon.

During the peak of the band’s popularity, Junoon were up against deeply ingrained cultural prejudices, typical of Pakistan’s hardline clerics. Music is haram, or sinful. Rock encourages Western devilry like sex and drug use, and so on. It’s about hedonism, not emancipation. Junoon may very well have produced anthems for a generation. However, these songs were never powerful enough to overcome the schism between liberal city youth, and growing community of disenfranchised Pakistanis, many of whom had been raised to hate music altogether.

For all of Junoon’s innovation, it will likely take someone more original to overcome such barriers. If such a bridge is to be musical, then it will be an artist that successfully articulates the interests of Pakistani society, as a whole. Certainly, the traditional aspects of Junoon’s music speak to such a possibility, however indirectly. Then again, perhaps it’s not the music so much, as it’s a change in attitude that’s required, to make better use of the bridges bands like this have already built. My bet is on the latter scenario.

Photograph courtesy of Majed’s Blog. All rights reserved.