A U.S. Supreme Court decision set to come out this summer could decide the fate of the nation’s public sector unions, and judging by the temperament of the court’s conservative five-member majority, it looks as if labor is bracing for a powerful punch to the gut. The court’s acceptance of the idea of that money is tantamount to speech means that a decision in Harris v. Quinn could mean the end of the “closed shop” in government employment. In other words, public employment could no longer require a worker to pay dues to the union that bargains for that worker’s wages and benefits.

This would be a critical blow for these unions, because it would greatly reduce the cash flow into union offices, and therefore hinder their ability to function and serve members. Small locals could go into severe financial trouble. Larger ones might have to stop their campaigns to reach out to workers to ensure that they sign union cards and pay dues. (Disclosure: Readers should know that the author is employed as an editor for a public sector union in New York City.)

Since neoliberalism has steadily killed off American manufacturing since the 1970s, the government sector has been the center of labor’s power. The 2008 financial crisis allowed state-level Republicans to exploit the economic pain to downsize government, which of course means weakening public sector workers rights. It started most dramatically with Wisconsin ridding workers of there of collective bargaining rights. In Detroit, the city cited its bankruptcy as a reason not to fulfill some of its pension obligations. And not a day seems to pass in the right-wing media when all of the world’s ills are blamed squarely on unionized public school teachers.

It’s very easy to blame this as the final phase of the Reagan Revolution, where the New Right began an attack on federal government services and unions, destroying major aspect of both and pulling the Democrats away from class politics and to the political center (Something similar happened at the same time in the United Kingdom with Margaret Thatcher, the unions and the Labour Party). But there’s an alternative narrative.

To borrow a theory from Daniel Gross, an anarchist trade unionist most famous for leading efforts to organize Starbucks baristas, American labor’s decline goes back much further than the rise of the Gipper, to the 1930s, which is most often thought of as labor’s finest hour, when after widespread labor unrest the government enshrined the right to organize in the National Labor Relations Act.

The alternative view is that this codification meant no longer could labor be an organized opposition force to capitalism, or any vehicle to organize workers not just for better wages and benefits, but for a post-capitalist future. Instead, unions became dependent on employers and the government for their power, creating a tripartite political understanding that would remain until the 1970s. In that time, radicals were purged from unions, and while today there are unions like the Industrial Workers of the World, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America who advocate that progress comes from confrontation, rather than collaboration, with employers, their numbers are small and voices absent from the discourse.

And so this partially explains labor’s exclusion from 1960s radicalism—recall Mario Savio’s famous Berkeley Free Speech Movement speech in which he vowed that students should not be molded by business, government or organized labor, the latter seen as just as big a part of the establishment as the other two. Today, unions find themselves at odds with progressives and radicals on a whole host of issues. The United Mineworkers of America are against new environmental regulations, and construction unions are fighting environmentalists who want to block the creation of a new oil pipeline because it will create jobs. Unions in upstate New York squirm at criminal justice reform measures that meant fewer inmates, which means fewer prisons and fewer prison jobs.

The fact is that despite the right-wing rhetoric that unions are a left-wing enemy to industrial order, unions are historically tethered to the interests of American capitalism. In purely Marxist terms, in the time of détente, from the 1930s to Reagan, unions helped workers recoup some of the surplus value extracted from them in the form of higher wages and benefits, but still allowed enough surplus value extraction in order for business to profit and eventually grow. For blue-collar workers, it was a pretty good deal; this allowed workers to own homes and cars, send their children to college and participate in the political process.

But as Thomas Piketty’s celebrated new history of capital suggestions, wealth has a tendency to concentrate, so this agreement became untenable. Moving production to the Global South solved labor questions in the industrial sector, driving down wages and forcing the working class into largely non-union service sector. That left the government sector.

What has happened there? It can’t be off-shored, but it can be outsourced. As economic journalist Doug Henwood explained, the opening salvo for neoliberalism in the domestic realm was the solving of New York City’s financial insolvency crisis of 1975, which reorganized public institutions, such as City University, which after that was no longer tuition-free. Going forward, the rhetoric that costly services could bring about another crisis (Republicans like to compare our already modest welfare state to Greek debt crisis, which is lunacy for a whole host of reasons) has put almost all government services up for sale. Even public education, once thought of as sacrosanct, is being handed over to the private sector in the form of charter schools.

And since this time, unions have been estranged from any kind of anti-capitalist project, and have no immediate political avenue to oppose the attacks coming from both government and business. It seems pretty easy to think that everything from the Republican assaults on labor to Democrats’ lackluster defense of unions, to the Supreme Court decision to financially devastate unions, would be the impetus for organized labor to think more radically. Unfortunately, it’s not happening. Perhaps the end of the closed shop will force unions to understand that any new deal with business and government, like it had in the 1930s, is all but impossible. But that would be silver lining to a very dark cloud.

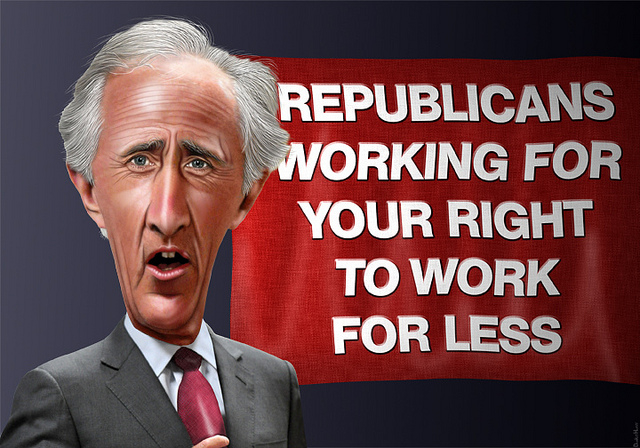

Photographs courtesy of DonkeyHotey. Published under a Creative Commons license.