For all his shortcomings, I find Sayyid Qutb to be treated somewhat unfairly. This was probably inevitable. After all, Qutb’s prison writings as a disenchanted member of the Muslim Brotherhood helped inspire two of the region’s most fear-inducing ideologies: Islamism, and Salafi jihadism. In the fifty years since his 1966 hanging, though, and especially given the advent of the War on Terror, his impact on modern jihadist groups is most remembered.

Most Westerners who know him at all are usually employed in security agencies, and make a habit of attaching phrases like “Godfather of al-Qaida” to his name. This is valid. After all, Qutb’s revelation in his 1964 revolutionary manifesto Milestones would eventually inspire many jihadists:

“Preaching alone is not enough. Those who have usurped the authority of Allah, and [who] are oppressing Allah’s creatures are not going to give up their power merely by preaching.”

Let’s be clear, though. Qutb isn’t outlining the September 11th attacks here. He is adjusting his existing revolutionary outlook based on new conditions. The reason he was in prison in the first place was because of Gamal Abdul Nasser‘s massive crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood, of which he was a member. While Qutb was content with economic and humanitarian projects as a means of realizing Islamic socialism beforehand, this certainly was not the case afterwards.

He came to understand revolution not as a gradual process to be realized through personal reflection and raising the spiritual consciousness of the oppressed ummah, but rather, as a violent and cataclysmic event that immediately replaces the existing order with an Islamic state. Readers may notice that this seems like an Islamist version of Leninism, which is correct.

Like many Leninists, Qutb believed that power must be seized directly, and then distributed to the revolutionary populace. His ideas on this were so influential that they would eventually affect Ayatollah Khomeini after he, along with many Muslims, was pushed to political Islamism by the apparent failure of pan-Arabist socialism in the Six Day War.

The consensus about Qutb is perfectly fair up to this point. It turns unfair when we turn to an often unposited question: what did Qutb even mean by “Islamic state”?

Many analysts, especially if they are self-decorated “terrorism experts,” simply assume that the answer is something like the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. However, Qutb would have probably opposed that project as well. We have to remember something. He wasn’t some half-literate preacher babbling about Muslim chastity. He was an energetic scholar who was both a Communist and revolutionary Islamist.

Qutb became a follower of Hassan al-Banna‘s Muslim Brotherhood not simply out of religious zealotry, but also because in its early years, the Brotherhood was at the forefront of discussions about Islamic socialism. Decades of anti-Brotherhood propaganda, and its own shift towards Wahhabism after crackdowns like Nasser’s sent many of its leaders to Saudi Arabia, has obscured this early history.

Recent trends have also done their part, such as Islamism’s shift away from alternatives to market-driven society, an assumed synthesis of the Muslim Brotherhood with militant groups like Hamas, and an arrogant attitude among Western leftists that Islam cannot be reconciled with a socialist vision.

For Qutb, though, it was simple. He was always disgusted by the insufferable yoke of materialism, and his time in the United States made him additionally shocked at the ferocity of American racism. Interestingly enough, he also shared a hatred of jazz with Theodor Adorno, and many of Qutb’s criticisms of Western culture were expressed in obviously different terms by Jewish exiles like Ernst Bloch.

The Muslim Brotherhood offered him the ability to tackle all these social problems comprehensively, through what founder Hassan al-Bana envisioned as a reassertion of Islam as a complete social, political, and economic system. Qutb did not see that totality of vision as including liberal democracy, and certainly not the economic machinery of Anglo-American capitalism. He also did not advocate for a return to the pre-capitalist Rashidun Caliphate, which is what frames the vision of other radical Islamists.

Qutb envisioned a supranationalist ummah that was unified in its submission under Allah. He reinterpreted the Prophet Muhammad’s original disgust for earthly intermediaries between humanity and the divine under modern conditions. For Qutb, the ummah was best served through a radically egalitarian outlook that framed a variant of anarcho-communism, with shariah councils that operated like soviets, and the like.

I think it is unfortunate that this part of Qutb’s legacy has been lost in popular discussion. As I said earlier, this may have been inevitable. After all, violent revolution tends to bring other psychological qualities to the forefront that are very difficult to reconcile with democratic politics in peacetime. Theorists that advocate it are frequently only remembered in those consequences. Certainly, the often aggressive politics of Islamist groups that followed Qutb, especially that which just occured in Egypt, make his ideas of Islamist vanguardism seem laughable.

We still need to recognize where Qutb had a point, though. There were critical reasons that he sought to discuss Islam in this manner. Among them is the fact that he recognized that in an era of Nasserist authoritarianism, Communism needed to be restored to its ethical base. He was not alone. The apparent death of idealistic leftist politics by the bluntness of crude materialism was a major point of contention at the time.

There was a despair in the air that Qutb sought to answer. He was not all too different from other figures of the era in that he despised the free market and socialist degeneration equally, and wanted another way out. Islamism was originally that for many people, and this remains the case, even as leaders like Recep Tayyip Erdogan fuse Islamism with the marketplace.

Of course, we have to be careful. Qutb’s vision can easily argued to be more fascist than it is socialist, even with its hostile attitudes to centralized power. Anti-capitalism isn’t enough. The right structures need to succeed established societies, and in his love for a fetishized interpretation of Islam, Qutb certainly falls short.

He was right about one thing, though. Human societies need to answer the spiritual and material needs of the people who inhabit them. At the same time, Qutb was wrong to argue that states like the Soviet Union and United States were not doing this by divorcing religion from public life. They may have been officially secular, but this wasn’t the problem.

The real issue was that there actually was a spiritual need being met. It just happened to be violent, and tied to domination. Deeply flawed ruling ideologies permeated throughout Soviet and American society as overall value systems, to much the same effect as religious practices. Every level of society reflected the dysfunctions of unethical governance and a democracy that was only barely manifest. He didn’t see religion’s absence in the United States. He saw what happens when sanctioned value systems have limitations that need to be overcome.

That remains the case, and for an entire generation of young people who were politicized by the Arab spring, Qutb still has strong ideas about the path forward. As with any theorist, though, we need to push the spirit of Qutb against what we are taught about the man. After all, his core grievances still articulate the pain of millions of alienated and oppressed Muslims all over the world. Ignoring that would be a travesty.

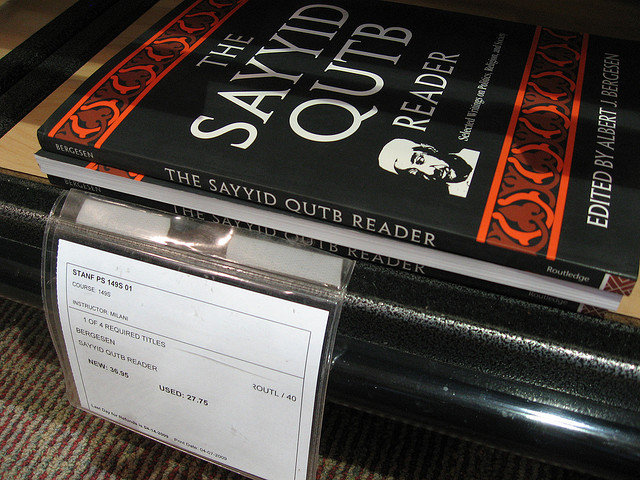

Photographs courtesy of Jay Bergesen, Rizwan Sagar, and Al Hussainy Mohamed. Published under a Creative Commons License.