Despite what the longbeards growing arugula on their rooftops in Brooklyn — or Berlin — would have you believe, there may be nothing less sexy than sustainability. That’s no dis. We are programmed, whether biologically or culturally, to seek out the sort of bliss that is, by definition, gone right after it comes. And that’s a problem for any politics that wishes to depose the prevailing social order.

It also helps to explain the allure of rootless radicalism. Your movement may not have a plan for achieving results after the revolution. You might not even dream about that time. Yet no matter how confused and inconsistent your ideological program, it can survive so long as it turns people on sufficiently.

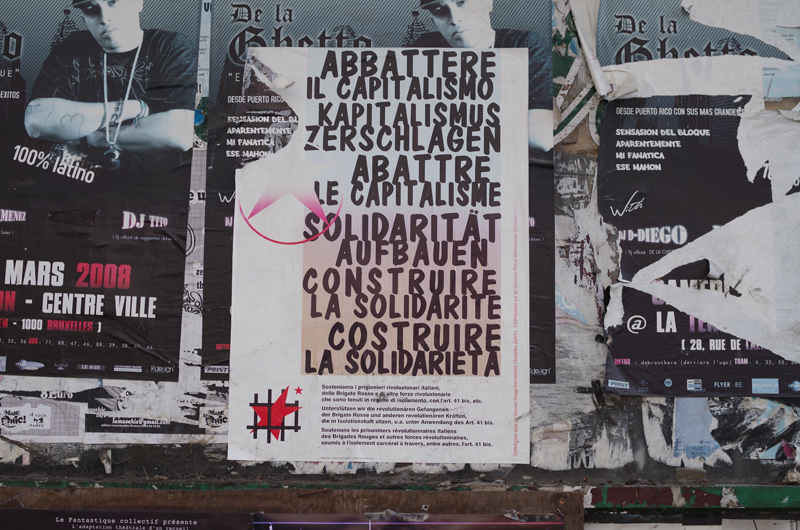

Surely, this is the lesson of these matching flyers pasted onto a wall in Brussels recently. Although figures like Toni Negri continue to suffer because of their association with the Red Brigades, the Italian group hasn’t been a viable force in decades. And the Red Army Faction — better known in the United States as the Baader-Meinhof Gang — is even less relevant. But in a world where the War on Terror continues to dominate international decision-making, these organizations’ willingness to go all the way, free from the taint of compromise, guarantees them a rich afterlife.

We tend to forget, when governments preoccupy themselves with the threat of religiously inflected insurgencies, that the terrorist threat they pose was modeled, to a degree, on these putatively Marxist organizations. While the Red Brigades and the RAF looked to the post-World War II struggle against colonialism for inspiration, their successors as Public Enemy Number One have turned to them for guidance, particularly where the media is concerned.

Seeing how much attention a small number of radicals could get by prioritizing style over substance, groups like al-Qaida have self-consciously focused on maximizing short-term effects. Although their members would surely decry the decadence of the radicals who put the Red Brigades and RAF on the nightly news in the 1970s, they share with them a conviction that death, whether little or big, is more appealing than life.

Considering how bleak the future appears to most young people in the world’s privileged places, much less its poorer regions, it makes a perverse kind of sense that the seemingly discredited rhetoric of the Red Brigades and RAF would be in circulation again. The furor stirred up by The Coming Insurrection a few years back derives, in large measure, from this revival. Although the tract’s anonymous authors tend to be considerably more measured than their predecessors from the Me Generation, the mere fact that they advocate taking physical action against the state conjures the specter of “revolution for the hell of it.”

Although it is extremely unlikely that organizations like the Red Brigades and the RAF could maintain their high profile for years, as was possible in the pre-digital era, short-lived equivalents could keep springing up despite constant surveillance. Indeed, many security analysts suspect that this has already happened with al-Quaida, with copycats acting in its name in the absence of central planning.

Perhaps, then, the initially shocking sight of these flyers in 2014 testifies not to the imminent revival of the Red Brigades and RAF as we knew them, but the realization that the safest identity for revolutionaries to assume these days is one that no longer exists in any meaningful way. After all, sex in the past is a lot more sustainable than sex in the present, because it can always be revisited in memories. The bliss may not be as intense, but it’s a lot more sustainable.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch; photographs by Joel Schalit