Monday was Memorial Day in the United States a day to reflect on those who have died, willingly or not, for their country but also a day to reflect on what the commemoration of their deaths means politically. Established in the aftermath of a brutal civil war, it implicitly served to bring a divided nation closer together. Perhaps that’s why it has felt more important in recent years.

While talk of unprecedented partisanship is overstated — no one in Congress has fired a gun in anger recently, as happened in the nineteenth century — there is no denying that the last several decades have witnessed an intensification of antipathies among ordinary citizens, most of which are either regional in nature or, confusingly, coded as regional regardless of where they actually manifest themselves.

Not many Americans are likely to describe themselves as part of a diaspora. But that is more or less how progressives living in the very conservative suburbs of Atlanta or country music fans on the Lower East Side conceive of their situation. They are minorities where they are, but always aware that they might be in the majority somewhere else. So much of the posturing that takes place in the country’s public spaces is rooted in the need to declare this sense of displacement.

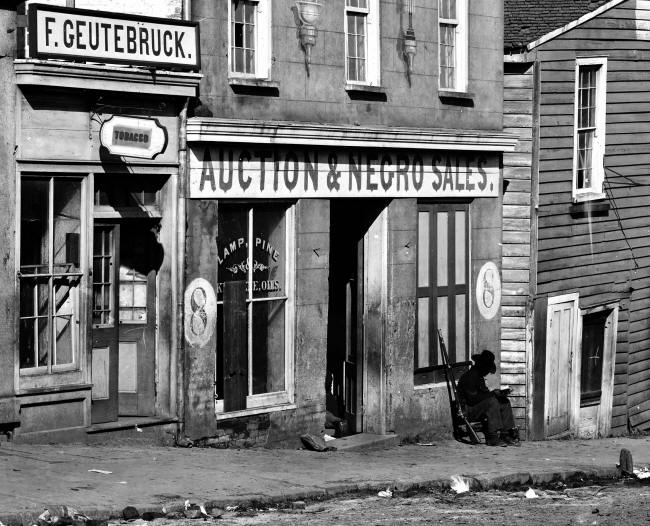

Of all the slogans and symbols people use to show where they are coming from existentially, if not literally, the Stars and Bars of the Confederate States of America may be both the most common and most controversial. Whether in the form of a decal discretely affixed to the lower back corner of a pick-up truck’s window or a four-foot-long banner flying from a flagpole anchored in the middle of that truck’s bed, as I recently witnessed, it signals a complex refusal of the dominant narrative in American history.

Nearly a quarter century ago, I saw the pioneering Cultural Studies scholar Dick Hebdige give a lecture on the use of the Confederate flag in Scotland in which he argued that it had become sufficiently decontextualized there to be able to stand for rebellion against a centralized authority without simultaneously conjuring the specter of racism. Much as I loved Hebdige’s work, it struck me as a dubious claim then and even more so today, in retrospect.

Because while that flag certainly does symbolize resistance to the victor in a civil war, be it Washington D.C., London — or, in theory, those parts of contemporary Europe where animus against the supernational authority in Brussels and Strasbourg is strongest — it can no more be shed of its association with the slavery-dependent Southern lifestyle than the swastika can of its association with the Nazis’ program of genocide.

That’s why many of the people who would proudly fly the Stars and Bars here in the United States feel compelled to find other, less obvious way of making their ideological convictions known. And one of the most popular and least likely to stir antagonism is declaration of support for the nation’s armed forces.

Although ambivalence or even hostility towards returning troops was a problem during the Vietnam War, ever since the first Gulf War, Americans have been urged through relentless reminders in the media to honor veterans regardless of where they fought or what they did. Simply put, there is no easier way to marginalize oneself in the post-Cold War United States than to call this reflexive commemoration into question.

For most of the year, active acknowledgment of one’s support for the troops, whether in the form of bumper stickers, T-shirts, pins or flags, might be construed as a partisan statement by many. Not because the military or military families are necessarily conservative, but because of the way conservatives have attacked more liberal Americans for insufficient patriotism since shortly after the end of World War II. Memorial Day, however, has historically been a time when this partisan discourse gives way to a more inclusive one. Even in the era of Fox News and right-wing talk radio, non-partisan love for one’s country is still exalted in theory. One does get the impression, though, that the pressure threatening to disintegrate this ideal is mounting.

Consider the way the nation’s Major League Baseball teams have recently started celebrating the holiday, wearing uniforms with camouflage numbers and, in many cases, camouflage caps to match. It seems a little desperate, as if spectators in the ballpark and at home wouldn’t be able to share in the task of remembrance without these props. A similar sentiment is conveyed by the many Memorial Days in circulation on social media, which increasingly seem to stand for a “holiday” from political regionalism.

Once the day is over and people have gone back to work or school, whether fortified or fatigued by the three-day weekend, this sense of fragile solidarity — which, to be fair, is surely less tenuous than the sort experienced in the immediate wake of the Civil War — yields to business-as-usual in the nation’s public spaces, in which expressing one’s support for the nation’s troops usually goes hand-in-hand with denigrating its current President and all of the supranational conspiracies he is made to embody.

While there might not be an actual Stars and Bars to signal this metamorphosis, the American flag that once represented the Confederacy’s enemy and post-war oppressor seems, paradoxically, to take on its role. Instead of standing for the Union, it actually communicates disunity. For all of the animus against Washington and the Federal government it metonymically represents, the nation’s flag then becomes an emblem of the diasporas who make resisting the so-called “Liberal Elite” their highest priority.

Commentary and photograph by Charlie Bertsch