I was harassed by neo-Nazis in Görlitzer Park. It was the night before an NPD rally in Berlin, and I was in the center of a large group of suburbanites who were dancing to techno, and looking at me strangely. I was only there because I was looking for one of my friends, but found myself cornered by two skinny twenty-somethings dressed in black, and sporting crew cuts.

I posted the dialogue of what happened next on Facebook, cutting out the part at the end where I walked away flipping them off because one of them yelled out, “stop! You’re under arrest!” I figured that it made me look more sympathetic.

Dude in leather jacket: “Wer bist du?”

Me: “Can you speak English?”

Him: “Um, okay, sure. (As an aside, I know, right?) Excuse me, what are you doing? Are you taking pictures?”

Me: “No. I’m just texting a friend.”

Him: “Okay well I saw a flash.”

Me. “There was obviously not a flash.”

Him: “What country are you from?”

Me: “Why would you possibly need to know that?”

Him: “I am a police officer and I need to know. Why are you here? What country do you come from? India? Pakistan?”

Me: “What does that matter? I’m here looking for a friend.”

Him: “Because you seem like you are on drugs or selling drugs.”

Me: “What because I’m foreign? I sell drugs because I’m foreign?”

Him: “Because of your overall appearance. Your face and clothes are very dishevelled.”

Me: “Okay, I’m not doing this.” *walks home*

I’m not entirely sure why I posted it in the first place. Maybe I was hoping for some affirmation and community after a tremendously isolating experience. Yes, Facebook is shallow. ‘Likes’ are not the same as hugs. Comments of “I’m so sorry” do not nearly remedy the violent exclusion. However, it is the most that my predominantly lighter-skinned friends can offer, short of direct intervention. There is something to be said for empty platitudes.

Especially since I know far more about what white people shouldn’t say at a time like that, rather than what they necessarily should say. I have no idea how the ideal reaction would look, because really, how do I even begin to express what I want to hear after incidents like that?

They are framed by a type of saber-rattling Aryan supremacy that reminds me just how many people see me as a wad of pigmented guts, terminating in Kalashnikovs and overactive genitalia. The last thing I need to feel is more isolated, because people hear me talk about it, and don’t know what to do or say.

After I described some details, like what they were all wearing, a friend told me to call the police. However, I was far more content with embracing the alienation I felt, pulling a warm jacket around myself, and disappearing inside a Neukölln shisha cafe. There, far away from the apparent violence of mainstream German society, I lost myself in the gentle massage of apple shisha. I breathed in the ashy flavor, and smiled as I exhaled and watched the smoke dance to the rhythm of crackling Oum Khaltoum recordings.

I avoided calling the cops for several days. My friend gently encouraged me to do it by saying that “the cops in Berlin aren’t like the Americans; they really do take this stuff seriously.” It certainly addressed one of the reasons for my hesitation. After years of dealing with racist counter-terrorism officers, I have become deeply cynical (perhaps unfairly so) about any manifestation of the police and its mandate to protect and serve.

But it wasn’t just that. I felt the same insecurity about reporting the neo-Nazis as I did with my Grade 12 music teacher when I was a student at Oakridge Secondary School. My friends told me that when I was absent one day, she responded to a student who called me a stud with a remark about my sexual abilities, “of all the things I would call Bilal, I would not say ‘stud.’”

I hadn’t thought about the experience for years, but in the days following Görlitzer Park, I suddenly remembered very clearly that I was almost neurotically opposed to the idea of reporting her. This was despite it being clearly inappropriate, and me feeling too humiliated to return to class. I was as frustratingly confused with my shakiness then, just as I currently was with calling the Berlin Polizei.

It makes sense now that I better understand how domination works. I grew up as the youngest child in a dysfunctionally abusive Pakistani Muslim immigrant household. I was physically and emotionally tortured on a semi-daily basis for the entire period from when I was seven, to just after my twenty-first birthday. I was raised to defer to aggression and fear authority. Is it any wonder that I was still instinctively doing it with music teachers and neo-Nazis?

The reasons why aren’t complicated. There ultimately isn’t that much of a psychological difference between an abusive family, community, and state. The abusive home is a germ-cell that lays the groundwork for other authoritarian settings. It teaches you to internalize the aggression of your superiors, and actively repress your desire to rebel against them.

There was a dark truth to my primary abusers claiming that they were “preparing Bilal for the real world.” It turns out that the preparation was so total that it was nearly impossible to forget in a situation where I was clearly in the right. Eventually, though, I swallowed by displaced fear, and called the Polizei to explain what had happened. They sent a patrol car to retrieve me, and the harassment was linked to the next day’s neo-Nazi rally. I was told not to expect it on a nightly basis.

I am still shocked and empowered by how seriously they took it. No matter what jaded leftists say, German police really are far better than their American counterparts. It feels strange to write that. My German friends say that as schoolchildren, they learned all about how the United States led the initial dissolution of fascism in Western Europe. Their textbooks say that imposed policies and tribunals like that which occurred at Nuremburg helped transform Germany into a democracy.

It is bewildering to me that seven decades later, an embattled minority like me now finds the United States to be the more proudly discriminatory country.

When I was in New York City on the tenth anniversary of September 11th, I walked through a Hasidic Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn to meet a professor in a Williamsburg coffee shop. After about half an hour, I was pulled out by six NYPD officers who proceeded to interrogate me on the sidewalk about what I was doing in the city that day. I remember a friend later joking that for attracting so much attention, I was “now officially the blackest Pakistani on the planet.”

There may be some truth to it. When I was at Görlitzer Park that night, I found myself avoiding the gaze of black men standing by the park benches. A large number of them were African migrants who had found employment selling drugs, and I began letting myself stereotype all black men in the park so that I wouldn’t have to keep awkwardly saying “no, I don’t want any pot.” An hour later, I was accused of doing the same thing.

One of the private traumas of Islamophobia for professional-class Muslim immigrants is that we are suddenly “being treated like niggers.” Alienated Muslim immigrants have always been able to trust that for all the racism they experience, especially after September 11th, “at least we’re not black.” That sort of anti-blackness that Muslims insist on expressing, even while actively experiencing anti-Muslim sentiment, blinds us to what is really going on.

Most Muslims who have been exhausted with the police will agree that the War on Terror allowed for Islamophobia to take root in public institutions. This is true, but it’s only half the story. The War on Terror has gone further to destroy the entire illusion of a politically-correct society. It has allowed for the populist assertion of racist views that were always bubbling under the surface, and every minority group has been negatively affected by it. Essentially, it destroyed the entire notion of a politically-correct society.

Despite the important differences in our levels of structural enfranchisement, every minority group has been negatively affected by it, especially as a result of the nightmarish feelings of blue-collar white powerlessness unleashed by the 2008 financial crash.

It is suicidal for middle-class Pakistanis especially to propagate any form of racism in such a setting. I am actually grateful to those neo-Nazis for reminding me of that.

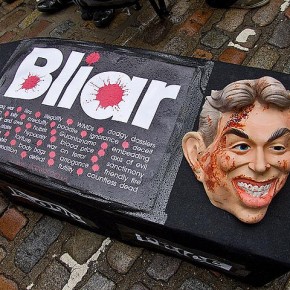

Photographs courtesy of Montecruz Foto, Michaela, and Michael Tapp. Published under a Creative Commons License.