It’s a shame Washington Post film critic Ann Hornaday expressed her ideas so inelegantly, because the relationship between entertainment and a culture of misogyny bear scrutiny. After all, the ghastly Isla Vista shootings have generated several public discussions about gun violence and regulation, mental illness, and in particular misogyny.

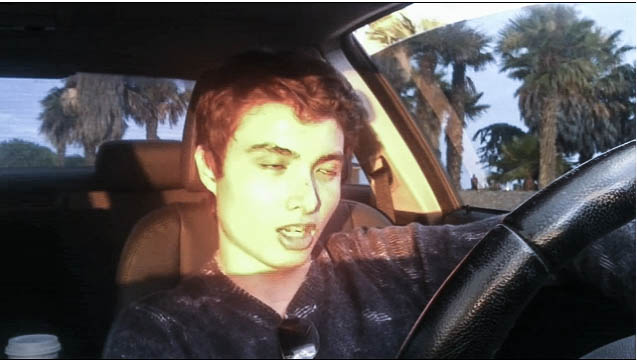

There is no way around the last given Elliot Rodger’s video, raging at the women who rejected him, or his reported disillusion with the community of pick up artists. His assault cast into relief the daily threat of toxic misogyny that pervades everyday life for women—a reality that has received attention through the brilliant #yesallwomen. And as happens all too often, people rush to the fore to derail this conversation, accusing the speaker of some greater ostensible wrong or absolving oneself of any complicity.

This is what happened to Ann Hornaday. After naming Judd Apatow and Seth Rogen in her larger argument regarding the symbolic violence bolstered and perpetuated in popular culture (a topic brilliantly covered by Anita Sarkeesian of video blog ‘Feminist Frequency’), the backlash was immediate.

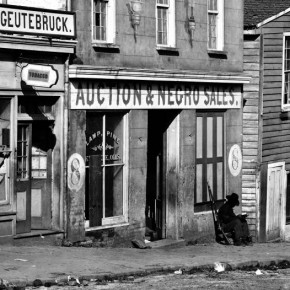

To be sure, Hornaday could have expressed these ideas with more thought and nuance, but her point regarding a ‘steady diet’ of films where men ‘get’ the girl is something to ponder: After all, how many of these films, and those that preceded, present women not so much as fully formed human characters, but as objects to be ‘won’ after the boy man completes his journey? (Arthur Chu offers an astute analysis of this model.)

Although I can see how Hornaday’s poorly designed and ill-thought-out query stung, it was not commensurate with the response that followed. In a tweet, Seth Rogen raged that her article was ‘misinformed’. He did not engage the larger points of an industry that struggles to represent women on screen and behind the camera (was Hornaday misinformed about that)?

Rather, he was insulted that his (this schlubby man’s) ‘getting the girl’ was seen as somehow linked to this horrific episode. He did not, however, question this phrasing. Why are girls things to be ‘gotten’, by schlubs or otherwise? In effect, Rogen turned the argument into something about him, and not about the larger concerns to which Hornaday gestured. It was once again about the male protagonist, this time with the woman as impediment.

Apatow wasn’t much kinder in his deflections and derailments. He suggested that her post took attention away from the issue of mental illness. And he suggested she was not much more than an attention whore, seeking to ‘milk tragedy’ and ‘maximise clicks.’ He refused to engage with the larger concerns, and instead declared Hornaday to be ‘uninformed’ as well as venal, and clearly unthinking about other social issues.

I can understand bristling at the seemingly personal aspect of this, but he of all people should recognise that his work exists in a more popular, public, arena where it is up for discussion. If her work had been engaged, fine, but the response seemed both dismissive and personal. And in that regard, it also comes back to something all to familiar, and a case of how women’s work and comments are engaged on this broad and casual level (#yesallwomen). Perhaps it was easier to dismiss her ideas rather than to reflect on the reality of everyday misogyny.

It is this everyday that is what is so difficult to recognise, and perhaps what was also, for Hornaday, so difficult to articulate. The fact is that structural injustice and symbolic violence are mostly invisible, and typically felt only by those who are at the receiving end. And when they are exposed, too many respond by taking umbrage, feeling as if they are the ones under attack and who must defend themselves.

‘Not me!’ shout Rogen and Apatow, ‘Not All Men!’ Perhaps, however, when such issues are raised, however clumsily, we should take a moment to think, rather than rush to end the conversation. How can we work together to shift the cultural climate?