Given the current state of affairs in Ukraine, it’s hardly surprising that the Georgian-born Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov should yet again court controversy from beyond the grave. With the shooting of ethnic Armenian protester Sergei Nigoyan in January 2014 in Kiev – one of the first casualties to fall on the Maidan – a newly mobilised Ukrainian opposition found another potent symbol to invoke its cause’s tolerance and respect for diversity.

Over the continued insistence of Russian state media to the contrary, it is a point which continues to be loudly made. Ukrainian singer Svyatoslav Vakarchuk compared Nigoyan’s death with the 1964 film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Parajanov’s own contribution to Ukrainian culture (for which, many believe, he too was punished with four years in a Soviet prison). Parajanov became a symbol of Armenian-Ukrainian solidarity – at least that was the mood among some in Yerevan. “I made the best ever Ukrainian film … but what kind of nationalist am I?” cries the actor portraying Parajanov in a 2013 biopic. “I am a genius! Send me to Africa, and I’ll make the best ever African film!”

Sergei Parajanov, born in 1924 as Sarkis Parajanian in Tbilisi, Georgia was one of the Soviet Union’s most compelling and confounding artists. By the time of his death in 1990, he had captivated audiences in Western Europe, Soviet directors such as Tarkovsky, and remained a thorn in the side of the Communist cultural establishment. “Parajanov made films not about how things are,” remarked the actor Alexey Korotyukov, “but how they would have been had he been God.” The Color of Pomegranates, his best-known work, chronicles the life of Armenian ashugh (bard Sayat Nova,) played by the mesmerising Sofiko Chiaureli.

Inspired by the art of Persian and Armenian miniatures, it is testament to Parajanov’s belief that cinema was the great mute. To him, dialogue was often an extravagance or encumbrance, and the film is a series of vivid slowly moving still life portraits. The Color of Pomegranates was one of a trio of Parajanov’s homages to the folktales and legends of southern Caucasusia, together with the Legend of Surami Fortress, based on a Georgian tale, and the Azerbaijani-inspired Ashik-Kerib. ‘We were searching for ourselves in each other’ reads a title card in the Armenian release of the Colour of Pomegranates.

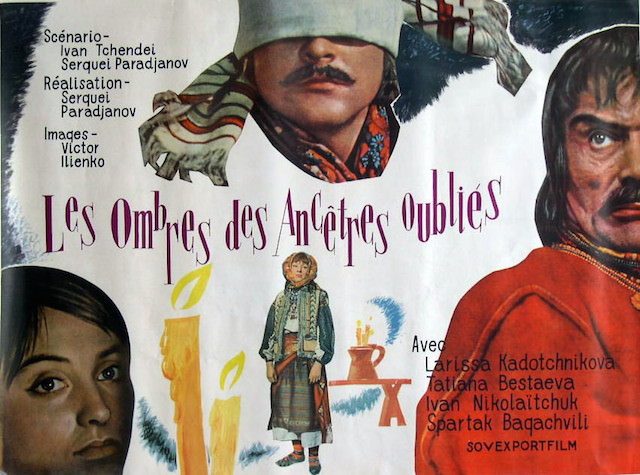

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Parajanov’s finest work, was described – though not dismissed – in its first international screenings in 1965 as “technically admirable if dramatically incomprehensible.” Set in a Hutsul village in the Carpathian Mountains in what is now northwestern Ukraine, the film is Parajanov’s interpretation of the book of the same name by Mykhailo Kotsiubinsky. It is a story about the love between two Hutsul villagers, Ivan and Marychka, against the backdrop of the harsh realities of rural life and behind the beguiling display of masks and costumes of Carpathian Ukraine.

Whilst the film’s subject matter – peasant culture and way of life – appears entirely wholesome and proletarian, Parajanov was no socialist realist, and the film had a deep impact on Soviet culture. As Alexander Steffen in his work on Parajanov writes, the film evaded the fate of many with an avowedly “national” content by not being dubbed into Russian upon distribution across the USSR – exposing its audience to a language – the strong Hutsul dialect of Ukrainian – that mainstream Ukrainian speakers sometimes found incomprehensible.

The film’s artistic innovation and rich portrayal of rural Ukrainian culture influenced the Soviet “sixties generation” (shestidesyatniki), who saw the emergence of more distinct forms of youth culture and modest political dissent. Some of the ‘traditions’ in the film – such as the emotional yoking together, to haunting Hutsul chants, of Ivan and his estranged wife Palagna – were later admitted by Parajanov to be his inventions, but the film was mostly well-received by the Ukrainian intelligentsia and, begrudgingly, the Soviet authorities. In the words of his contemporary, the Ukrainian poet Ivan Drach, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors heralded a new age for Ukrainian cinema.

Parajanov has always divided opinion, and by all accounts took immense pleasure in doing so. Ukraine’s choice of submissions to the 2014 Oscars were timely. Among their number was not only the film Khaytarma, on the deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar population from their historic homeland in 1944 by Stalin, but also Serge Avedikian and Olga Fetisova’s aforementioned biopic, Parajanov. In March, Fetisova publically refused to accept the Armenian government’s award for the film due to Armenia’s support for the referendum held on Crimea’s union with the Russian Federation.

The Russian Heritage Month being held in New York has also courted controversy by including the Armenian Parajanov’s work among its offerings. Armenians were further slighted not by Russia, but by Ukraine, whose admiration of the director of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors led to Ukraine submitting the Color of Pomegranates (under the title Sayat Nova) as one of its entries to the 2014 Cannes film festival, despite its avowedly Armenian content and inspiration.

Armenia has never seemed quite the same after discovering the Color of Pomegranates. It is a film ripe with ambiguities. Accordingly, Armenia has been the most proactive in claiming Parajanov’s legacy, with Yerevan’s Parajanov Museum. A fine old townhouse overlooking the Hrazdan Gorge on the very edge of the city centre, Parajanov’s house–museum has the dubious distinction of never having housed Parajanov himself. At least, not for long – the director only moved to Yerevan in 1988, and died of lung cancer in 1990, a year before his museum finally opened and the state which had imprisoned him dissolved itself as its constituent “national” republics broke loose.

The home is arguably one of Yerevan’s finest sights, if one can find it. Under constant surveillance by the looming, surrounding concrete tower blocks, it is a grotto of collage, canvases, and sculptures. On its second floor is a small collection of Parajanov’s medallions. Whilst imprisoned, the artist would collect aluminium bottle caps and, using his thumbnail, etch portraits from them – Tsar Peter the Great, Nikolai Gogol, Alexander Pushkin, and Bohdan Khmelnitsky to name a few, the last of whom is a Ukrainian national icon who led a revolt of Cossacks and Tatars in the mid-17th century against Polish rule.

These are poignant fragments of a theatrical and exuberant life. What would Parajanov have made of his life submitted to the Oscars, or his two Hutsul lovers summoning patriotic tweets of solidarity between the Maidan and Yerevan? Perhaps he would have awarded himself another milk-top medallion, salute playfully and laugh raucously, a pantomime general in a tin-pot, absurd yet beautiful world.

After all, as Parajanov is supposed to have said, to become a genius, you must stay in prison for at least two years. Otherwise, you could never become a great Soviet director.