The recent European elections left those who benefit from a laissez-faire continent concerned that “populism” could rebuild the walls they spent decades disassembling. Though many of the anti-EU parties have little in common beyond their hostility to Brussels, this term is still being used to describe them all. It’s as if traditional ideological divisions had ceased to exist.

Back in the 1930s, when the radical Right and Left were fighting in the streets of many European cities, the Establishment was similarly fond of this catch-all category. The masses were always in danger of becoming a menace. And sometimes all it took was for a demagogue to don the mantle of populist insurgency to realize that potential.

Beset on both sides, the Middle was in desperate need of defenders. The difference now is that, whereas this crisis played out in nation states during the Great Depression, it is now centered on the continent’s supranational leadership. Although today’s Middle theoretically comprises anyone who fears turning back the clock, its most vigorous defenders come from the world of Big Business.

Any corporation of sufficient scale to operate without regard to national borders stands to lose if protectionism restricts the flow of capital. That’s why The Economist, though hardly a fan of the EU’s regulatory excesses, still comes down squarely on the side of Europe. Markets constrained in the name of the People are markets that are bound to be less efficient than those that are free to span the continent.

From this perspective, perhaps it really doesn’t matter that much whether animus against the EU is arising in hearts seduced by post-fascist xenophobia or post-Marxist agoraphobia. But it matters very deeply to the people who identify with anti-Europe parties. Their self-understanding always exceeds the bounds of nationalism.

Perhaps they are most agitated by immigration and the “browning” of Europe it has been blamed for. Perhaps they worry about blue-collar jobs being moved from countries with higher wages and stricter labor laws to the former Eastern Bloc. Or perhaps they are fearful of Islam’s seeming displacement of Christianity as the continent’s most significant religious force. Whatever provisional alliances these groups might test out, their investment in the so-called “populist” parties is inextricably bound up with the particularity of their primary concern.

In other words, however hard the pro-Europe forces work to classify them together, they are unlikely to sustain meaningful solidarity as a continent-wide opposition. Unlikely, that is, unless the insistence that they together constitute a singular “populism” starts to sink in. Political blocs are rarely brought and held together by terminology alone, but it’s not a risk that the Establishment needs to be taking.

That’s why those of us who observe this conflict from the margins should do what we can to remind the participants that, whatever the merits of the anti-Europe position, it cannot yet be extended into a coherent ideology. For that, it would be necessary to share positive content, something that is still a long way from being the case.

There are good reasons to oppose a Europe that principally serves to increase the profit margins of transnational corporations. But the progressive solution can never be to aspire to less internationalism. It is both possible and desirable to respect locality without falling back on the fetish of nationalism.

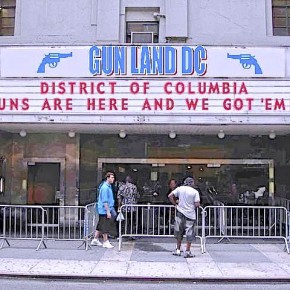

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.