Vulnerability is their middle name. Whether they’re washing dishes, or sweeping floors, everything they do communicates helplessness. Blow in their direction, and they’ll fall over. They’re that fragile. Such is the situation of Europe’s migrants. Whether from Afghanistan or Romania, their situation is consistently the same. They come from one crisis, only to be greeted by another. We hate them for their weakness. No one wants to admit that life can be as precarious, and as humbling, as theirs.

Few refugee crises make the headlines like the Europe Union’s do. Besieged, for all intents and purposes, by migrants from everywhere (including internally) their efforts to gain ‘entry’ are oftentimes so dramatic, and so tragic, that they’re impossible to ignore. The scale, and the repetitiveness of their deaths, routinely in the dozens, if not the hundreds, is heartbreaking. Drowning en masse in the Mediterranean, arrested as minors and forcibly repatriated to newer EU member states. They might as well be Jews fleeing Germany, in the years immediately leading up to World War II.

The 1930s analogy is not without merit. Not because it might reflect, as many leftists are wont to do today, the growing influence of populism, on how Europeans perceive minorities. It’s due to their callousness, manifest in an increasing intolerance of outsiders, both within and outside of the Union. A consequence of the now half decade-long economic crisis, as well as racist agitation, it’s a highly combustible mix, which begs for a careful reconsideration of borders. Not just those which ring EU member states, but those which we use to close off our sense of community, and fairness. The following flyer translation, from Berlin, is one such example.

Renaming Richard-Platz « Mohammed-Rahsepar-Platz »

On 29 January 2012, an asylum seeker called Mohammed Rahsepar took his own life in a shelter in Würzburg, Germany. He flew thousands of kilometers to Germany in order to escape threats of torture from an Islamic regime police force which had already cost him a kidney. However, the living conditions engendered by Europe’s asylum policies, which affect all refugees in so-called “safe Europe”, pushed him to suicide.

Earlier that day, Mohammed R. was brought to hospital where he complained about acute pains. No one helped him. He could not communicate with the hospital personnel, and after hours spent at the hospital without treatment and with no one to pay his return fare for the bus, he walked back to the shelter. When he got there, he hanged himself.

His suicide caused protests across Europe, some of which continue to this day. In 2012, hundreds of refugees met in Würzburg and ran to Berlin in order to highlight Europe’s unsustainable and criminal policies.

A protest camp was set up in Oranienplatz, Berlin. It opposed residential obligation, putting people in detention centers and deportations. It withstood opposition for two years. Today, there is still an info point on the square. The rest of the camp was evacuated after weeks of racist media coverage. The same happened to an occupied school in Kreuzberg. The school was always negatively portrayed, constantly mentioning “humane conditions” – yet no practical help was ever offered. The aim is not and has never been to meet the demands of the refugees. Instead, the City of Berlin reacted in the same way as Germany and Europe: with violence.

Out of despair (again), eleven people went on hunger strike in front of a church in Berlin (which refused to give them sanctuary). The state reacted by putting them in police custody. They were sent to detention centers across Germany and some were deported.

We are horrified by the ignorance of the German government and media in their handling of refugees. When people are so desperate that they are prepared to protest for years, go on hunger strike, sew their mouths shut and resort to suicide – we cannot sit idly by and watch. We struggle to comprehend how people with even a hint of compassion and who witness the terrors imposed on refugees do not take to the streets or find ways to show their solidarity.

As a small sign of our solidarity we have renamed Richardplatz “Mohammed-Rahsepar-Platz”. This will be a lasting symbol of the protests. We are doing this in combination with the “Freedom March to Brussels”, when activists and supporters marched from Strasbourg to the European Parliament in Brussels in order to protest against the repressive European migration regime.

We send them our solidarity and call on all those who agree with us to join our common action.

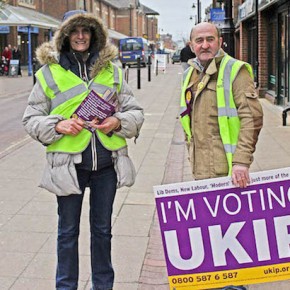

Translated from the German by Kit Rickard. Introduction and photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.