Make no mistake. Ferguson is the War on Terror exploding in a relatively unspectacular American town. The crackdown that immediately followed protests over Michael Brown’s shooting recalls, for many immigrant Muslims, the sort of violent excesses present in countries like Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan. This isn’t a coincidence. Domestic policing has been affected by foreign military entanglements since the occupation of the Philippines. War becomes a laboratory for state repression and counter-insurgency tactics that are inevitably used in the homeland. The increased use of drone technology inside the United States, after its widescale depoloyment in the War on Terror, is all the proof you need.

When you combine that with the explosion in military hardware being used by the police, the fact that September 11th ended the political-correctness of American racial discourse, and the brutal racism and poverty at play in Ferguson, you get scenes from Ferguson that recall the assault on Fallujah. This puts Muslims like me and Souciant contributor Shirin Barghi, who has gained quite a bit of attention for her series #LastWords, in a difficult position. How do we process and confront situations like this? For her, it’s about making transnational connections, and speaking against these problems in an effective way.

“Well, Ferguson spoke to my own experience as a Muslim Iranian woman,” she said in a recent interview. “Seeing the way the authorities here used terms like ‘rioters’ and ‘looters’ to dismiss and trivialize overwhelmingly non-violent demonstrations in Ferguson was painful. It brought back vivid memories of similar tactics used by Iranian officials against protestors in 2009.”

“While there is nothing inspirational about the long and terrifying history of anti-black violence, I would say the struggle to dismantle structures of oppression resonate with us. I came of age in a country where police violence and state repression was pervasive. While the shape and color of that violence changes from place to place, its fundamental characteristics are sadly predictable and universal.”

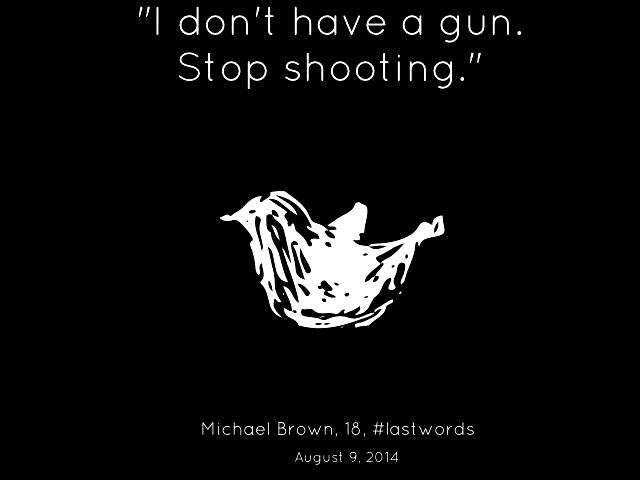

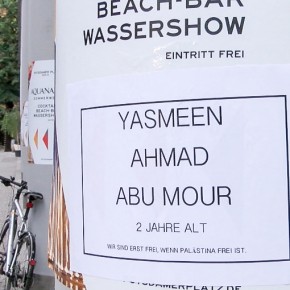

Last Words is Shirin’s attempt to work through these questions. The series puts the emotional spotlight back on victims themselves, displaying their final statements against a black backdrop with their names, ages, dates of death, and a drawing. Obviously, the simplicity is meant to elicit an intense emotional reaction. Shirin told me that she deliberately formatted the images this way to humanize statistics that, if taken alone, risk being essentially meaningless.

“As the extrajudicial killing of unarmed black people increases in number, it’s easy for these crimes to merely turn into numbers in the eyes of the public at large. Seeing these last words makes it harder to ignore their stories. We can all imagine ourselves saying these things. It makes us wonder what our last words would be if the police became violent towards us based on the color of our skin, something most people in this country, including myself, will rarely if ever experience.”

There are also purely analytical reasons that we should seek to move beyond statistics here. One reason is that numbers can end up clouding the power relations at play, by downplaying the ethical dimensions of social problems, rather than supporting critical analysis with scientific inquiry. Michael Brown’s death becomes a number, and systemic hiccup, rather than a moral travesty. Another is that reliable statistics may not even exist when it comes to police brutality, as journalist Reuben Fischer-Baum argues in FiveThirtyEight:

Efforts to keep track of “justifiable police homicides” are beset by systemic problems. “Nobody that knows anything about the SHR puts credence in the numbers that they call ‘justifiable homicides,’” when used as a proxy for police killings, said David Klinger, an associate professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Missouri who specializes in policing and the use of deadly force. And there’s no governmental effort at all to record the number of unjustifiable homicides by police. If Brown’s homicide is found to be unjustifiable, it won’t show up in these statistics.

If that is true, then the cases that do manage to get public and institutional attention must have their impact maximized as much as possible. Shirin clearly succeeds on that note.

It is easy to be cynical about human nature during events like those in Ferguson. However, there is a reason that Shirin’s series, which has also been featured in the Huffington Post, and Upworthy, has become so popular. You don’t have to be a Muslim immigrant who has experienced police brutality like Shirin (though as she emphasized to me, “not in the same way as black and brown folks here”) to be disgusted. Many Americans are shocked about what is happening, and concern about police militarization has gotten so intense that even conservative writer A.J. Delgado has written in the National Review about how the cops have gotten too vicious. There is an obvious worry about government violence in the United States right now, and it is fixated on the “Warrior Cop” that was unleashed by the unrest of the 1960s, and fed by decades of security state expansion and failed social policies.

Jonathon Ferrel’s image, seen above, doesn’t actually include a statement because he was killed before he could say anything. He probably didn’t even know what was happening. Americans are increasingly worried that heavy-handed law enforcement policies have taken on a life of their own, and that as a result, they too could lose control before knowing it. Our grim fascination with Ferguson is driven, at least in part, by our own apocalyptic anxieties. Tanks everywhere. Fires blazing on the streets. Pundits screaming on our televisions about the looting and social upheaval. Shirin’s question of “what our last words would be if the police became violent towards us” is therefore an important one.

Beyond all that, though, the crackdown in Ferguson is clearly a reminder of just how often black people are getting killed by the government services that are supposed to protecting them, and serving their interests. Ferguson isn’t actually about Michael Brown. For many protesters, Michael Brown is functioning as a projection for young black men who have been harassed, violated, and killed by the police for no justifiable reason. The best thing about Shirin’s series is that by emphasizing the moment of death itself, she reduces the issue to the only thing that really matters. Black corpses being produced by the intense violence of American life.

We will have to see what results from that. People are clearly angry and disgusted enough for things to change. However, translating their rage into a general demilitarization of American police departments, and a massive reexamination of their racial attitudes, is no easy task. We have to remember that this is a country so dysfunctional that it couldn’t even demilitarize private citizens after a mass shooting at a kindergarten. It seems clear that for any meaningful reforms to occur, there needs to be a level of political mobilization that far eclipses the protests in Ferguson. That seems unlikely without the formation of powerful grassroots movements. In the meantime, Shirin says that she plans on adding more pictures to her series. As we completed our interview, I thought about how much new material she would get before another black-heavy American town gets compared to Fallujah.

#LastWords pictures courtesy of Shirin Barghi.