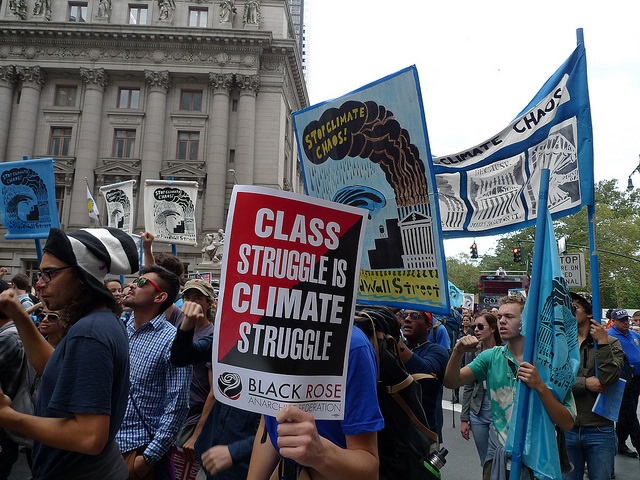

In April 1990, I helped organize the Earth Day Shut Down Wall Street action. More than 1,500 activists from the United States and Canada traveled to New York on the twentieth anniversary of Earth Day with the goal of halting the New York Stock Exchange for a day. We got close, with hundreds of protesters and cops clashing in front of the exchange doors. We wanted to expose corporations wrapping themselves in the façade of environmentalism and identify them as criminals responsible for scorched-earth business practices. I’ve been eagerly awaiting a return, and on Tuesday, I ventured down to the financial district for the Flood Wall Street direct action. The following are impressions of today. They are more tactical than strategic.

First, the turnout exceeded everyone’s expectations. We thought that it would be a thousand people or less, but by the time the march left Battery Park in southern Manhattan, the count was 2 500. There seemed to be a lack of coordination on the part of direct action organizers, while the NYPD took a surprisingly hands-off approach. It still lined the streets with interlocking metal barricades, so the protest only made it as far as Broadway, around the iconic bull sculpture, before settling in for the day. Activists trickled in all day and the consensus was that 3 000 people took over the streets at the peak.

However, there was no organized system like a spokes-council or general assembly to encourage them to stay put and decide the next steps. Nor were there resources like food, blankets, and water to enable a large enough number of people to hunker down. This would have made the cops hesitant to arrest them all. Luckily, there was a large media presence, including many mainstream media outlets. Flood Wall Street drew in more participants thanks to People’s Climate March NYC, which drew an estimated 300 000 participants. It was probably the U.N. Climate Summit, and the large media presence, that helped limit the NYPD’s notoriously aggressive behavior.

Still though, the police came out on top. The NYPD strategy was to outlast the protesters, and it worked. Cops were blasé about activists disassembling metal barriers. They would not rush to fight them, like they are known to otherwise. There was no kettling, which was highly unusual for a direct action. Instead, they ceded more physical and tactical ground than normal. The NYPD let protestors have Broadway around the bull for nearly four hours, and there were only a few officers present when everyone marched up to Wall Street and tried to push to the Stock Exchange. If there was more coordination, we could have definitely pushed inside.

One guy momentarily breached a barricade. He was grabbed and pulled through. Normally, that’s the moment when cops pile on the protester and injure him, but instead, they just tossed him back into the crowd. No arrest. No beat down. As the crowd began shoving against the policy, NYPD white shirts started using their fists and a few blasts of chemical spray. We were instantly pushed back. It had an unusual floral smell. It continued this way, with the NYPD taking a step back, and waiting for activists to get tired of staying. As a result of that, and a lack of activist organization to outflank the cops, by 6:30 PM, about 75 percent of people had left the streets, including me. Less than an hour later, the arrests began.

Why was the NYPD so hands off? During the whole day, there were multiple squadrons of fifty to a hundred cops stationed at different points a few blocks away from the action. This wasn’t the overwhelming force of past protests, that had thousands of them. I spoke to one community affairs police officer who said they were taking a “calmer” approach. He said it was more effective in a manner that made it seem like he was parroting the official line. He acknowledged that this strategy was determined by the higher-ups.

It was likely done this way because of a combination of factors: the Climate Summit, the heavy media presence, the legacy of Occupy Wall Street, the space created by the People’s Climate March on Sunday, and post-Ferguson concerns about police brutality. The NYPD also probably didn’t want to escalate things: after using pepper spray in Union Square in September 2011, Occupy became much more popular in New York City, and the Brooklyn Bridge arrests a week later turned it into a national phenomenon. There are also New York City specific factors. It is likely that Mayor Bill de Blasio was attempting to avoid controversy after rehiring Police Commissioner Bill Braton, who instituted the infamous Stop-And-Frisk policy in the 1990s and favors Broken Windows policing. To be fair, de Blasio may even be serious about getting the NYPD under control, but recognizes that it may not be the time to do it.

We can’t be certain if there will be another hands-off protest event like this. It is clear though, that an opportunity was missed. While there was a more enthusiastic spirit at the end of the day among veteran activists, there has been lower levels of organization over the last fifteen years of actions since the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle. Still though, it was a step in the right direction. One activist, Laurie Arbiter, summed up the feeling of many activists why actions like Flood Wall Street are on the frontlines of the climate justice fight. “It was unpredictable,” she said, unlike the Sunday march that felt scripted to many. “Climate change is unpredictable as well.” In other words, while marches are important and necessary, mass organized political chaos in the streets is more likely to destabilize the status quo, bringing forth a new social equilibrium.

Photograph courtesy of Susan Melkisethian. Published under a Creative Commons License.