Compared to other German cities or metropoles like Paris and London, Berlin has benefited from its lack of meaningful antiquity. Little more than a village prior to Prussia’s ascendancy in the 1700s and still not very impressive in Germany’s early years as a unified nation, it was free to develop as a fully modern city. Not only cartographically and architecturally, but ideologically.

There’s a reason why minorities and misfits felt so comfortable there in the era Walter Benjamin rapturously conjures in his Berlin Childhood Around 1900 and why they continued to regard the city as a refuge well into the Third Reich. Even under Hitler and his minions, the city projected an air of resolute anti-provincialism, mocking the pseudo-medieval pageantry and crude propaganda of the Nazi regime in private long after it was too dangerous to repudiate in public.

Even in the years immediately following World War II, during the lean years when West Berlin’s geography deprived it of access to the Federal Republic’s Economic Miracle and East Berlin was tightly controlled by a wary Soviet Union, the city still attracted artists and intellectuals who drew inspiration from its openness to both the past and the future. The very fact that the city wasn’t rebuilt like some sort of theme park version of itself, unlike many places in the West, felt liberating.

For some, the Berlin Wall actually reinforced this impression. The idea that the heart of the pre-war metropolis, including the fabled Reichstag, could be so thoroughly evacuated gave hope to those who had no desire to revive the past. More than any other European city, almost like Los Angeles or Sydney, Berlin seemed like a place where new ways of existing could be explored without the having to ward off the weight of tradition.

A lot has changed since reunification, obviously. Those empty places, like Potsdamer Platz, became redevelopment corridors. And moving most functions of the capital from Bonn back to Berlin served to rein in some of the city’s Cold War improvisation. But the concomitant economic revival, bolstered by miles and miles of relatively inexpensive housing, also turned it back into the sort of place people wanted to emigrate to, whether from elsewhere in Germany or beyond.

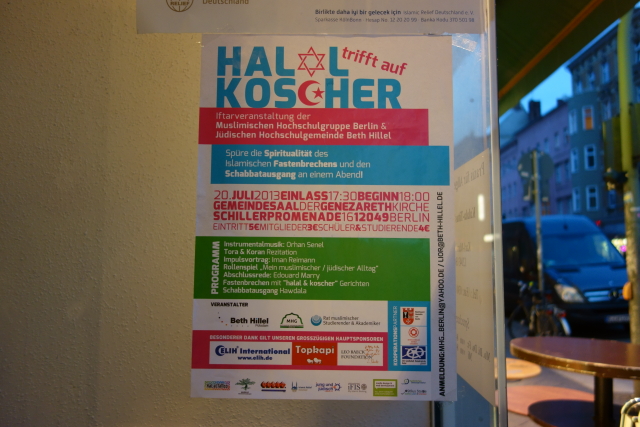

Right now, a good deal is being made of Berlin’s attractiveness to Jews who are turned off by both Israel and the New World, yet fearful of rising anti-Semitism elsewhere on the continent. Given Germany’s history, this attention is understandable. The truth, though, is that this has less to do with a specifically Jewish relation to the city than with its overall diversity.

Like New York in the early twentieth century — or even now, to a degree — Berlin is one of those places where being different is the norm. Whether one is Muslim or Jewish, from Africa or Southeast Asia, it’s not that hard to feel a sense of belonging. Or safety. The xenophobia that rules much of contemporary Europe finds it almost impossible to take firm hold because its bearers are simply outnumbered.

None of this is to suggest that Berlin is some sort of paradise. As tolerant as its inhabitants tend to be, they are probably still a little too aware of their efforts to promote that image. The casual acceptance of otherness that one encounters in New York, to give one example, still hasn’t been fully realized. But compared to most other places like in Europe, Berlin is inimical to monocultures. Some have boldly claimed that it represents a new Jerusalem. If we are thinking allegorically, this makes sense. The sad fact, however, is that the actually existing Jerusalem of the twenty-first century pales in comparison.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.

1 comment