Heroes are hard to come by in Europe. Even as the nightmare of two world wars recedes farther into the distance, the sense that they were the product of excessive belief persists. Had there been less passion to mobilize, the reasoning goes, the flames of nationalism would have petered out a lot sooner. But it is proving increasingly difficult to keep the continent bound together with “post-passion.”

Disillusionment may be less dangerous than idealism, but it won’t keep you warm at night. More than half a decade after the panic of 2008, most EU economies continue to underperform projections for recovery by a wide margin. To imagine that people would turn to their political leaders for inspiration under such circumstances is foolhardy. Most of them have been rendered impotent by a combination of international commerce and national debt. And the exceptions, such as Germany’s Angela Merkel, are so preoccupied with the consequences of that impotence that they rarely have the opportunity to promote a vision of the future that is more than a less dysfunctional extension of the present.

Where, then, is inspiration to be found? Some turn to sport, particularly football, to rouse their passions. During the World and European Cup, rooting one’s favorites can temporarily muster full-throated support for an idea of the nation. Yet there are limits to what a person can do with a Cristiano Ronaldo or Mario Balotelli for a role models, particularly on the political stage. To be sure, there was a time when almost all of country’s best footballers played for club teams at home. But the reality today is that business concerns take precedence over deep-seated national belonging.

It could be argued that this situation makes it easier to cultivate a sense of international belonging through sport, with these peripatetic superstars becoming a source of European pride. Unfortunately, most human beings today don’t seem to have been programmed for that sort of response. Whether it’s simply that the EU is too big to elicit that sort of investment or that the way it is currently structured is to blame, the flag of Europe is just now flown very often. Indeed, were it not for animosity on the continent against transnational corporations — particularly those based primarily in the United States — the EU would be hard pressed to inspire any solidarity at all.

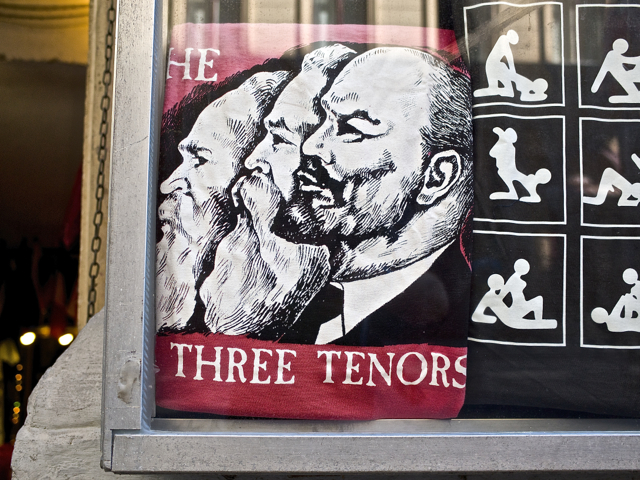

That’s what makes the lead photograph, taken in Budapest in August, so compelling. At first, the decision to bill the greatest heroes of the Left as the “Three Tenors” just seems a clever way to attract attention. Yet if we stop to think about this mash-up in greater depth it proves to be a surprisingly sophisticated meditation on the problem of European unity. It’s no coincidence that the first performance by the Three Tenors — Placido Domingo, Luciano Pavarotti, and José Carreras — took place as part of the cultural offerings at the 1990 World Cup, which was held in Italy and won, somewhat controversially, by the side of newly reunited Germany. There was a powerful sense at the time, in the wake of the Eastern Bloc’s collapse and reforms in the Soviet Union itself, that Europe was about to finally come into its own, no loner distracted by internal conflict and ready to equal and perhaps even surpass the United States as a global economic and cultural power, if not militarily.

Optimism was extremely high in Germany and newly liberated nations like Czechoslovakia, Poland and the Baltic States. But even in parts of the continent less directly affected by the decline of Communism, such as France, Spain and Greece, the belief that world had finally taken a sharp turn for the better was readily palpable. And somehow the three tenors, turning one of Old Europe’s most storied forms of art into a populist spectacle, gave voice to the inchoate feelings of those who were “watching the world wake up from history.” The fact that their performance took place right before the World Cup Final only strengthened the impression that they had find a way to preserve the best of the continent’s traditional without sacrificing liberty and convenience.

Yet for all the goodwill that first concert created, it’s difficult to look back on now without bemusement. It’s not the singing itself, which came out quite well despite the oddness of three tenors having to share arias, but how it was implicitly presented as an allegory for cultural reconciliation: the arts with sport, high culture with mass culture, and the outsized egos of Domingo, Pavarotti and Carreras. Today, these divides seem so firmly entrenched that it’s almost impossible to imagine overcoming them. In the summer of 1990, however, naïve optimism about the potential for bridging them felt like a foretaste of Europe’s common currency.

The beauty of transposing the Three Tenors concept for Karl Marx & Co. is that it subtly communicates the erasures that made that optimism possible. If Europe seemed to be more united than ever before, it was because — at least in part — of how much energy had been expended suppressing the International. In other words, projecting a sense of unity, however modestly, required abandoning the most compelling argument for trans-national cooperation. The irony was almost too rich to bear.

Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.