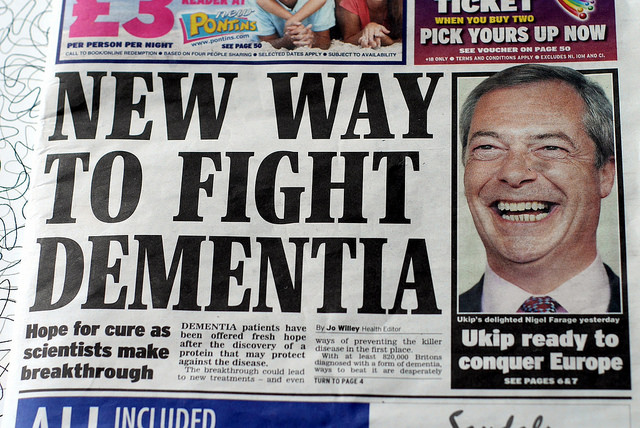

What was once unthinkable has become a reality. Nigel Farage will be partaking in the TV debates in the run up to the 2015 election, alongside David Cameron, Nick Clegg, and Ed Miliband. Perhaps the mainstream media concluded that the only way to keep political discourse alive was to inject Farage, and report on the consequences. The lesson is obvious: It’s impossible to ignore UKIP, and its rise to fourth party status.

It was only a few months ago that UKIP candidate Roger Helmer was easily defeated by mainstream candidates. It isn’t insignificant that it took an establishment candidate to secure the Party’s presence in Parliament. Douglas Carswell still stands as the kind of man UKIP sucks up in vast quantities. He stands opposed to universal healthcare and regulations on private enterprise. He wrote the Plan with fellow-traveling libertarian Daniel Hannan. It’s a free-market hymnbook for decentralisation and deregulation.

This is consistent with the reality of Farage’s success. The leap from 13 MEPs to 24 MEPs took five years, but the European elections only draw out 33.8% of the electorate. That’s half of the usual turnout in UK general elections. The entrance points are to be found in the weak spots of the Westminster consensus. Under these conditions the fringe parties can have greater influence.

UKIP gained 27.5% of the vote and outmatched Labour by a little over 2%. So that’s about 9.3% of the electorate. The Conservatives lost 4% of the vote, just as the Lib Dems lost 6% and were overtaken by the Greens at 8%. The vote for the BNP fell by 7%. Against this backdrop, it’s easy to see why UKIP bolstered its vote by over 10%. If you take the local elections, the Farage party lost 5% of the vote, but picked up 160 seats and gained no councils.

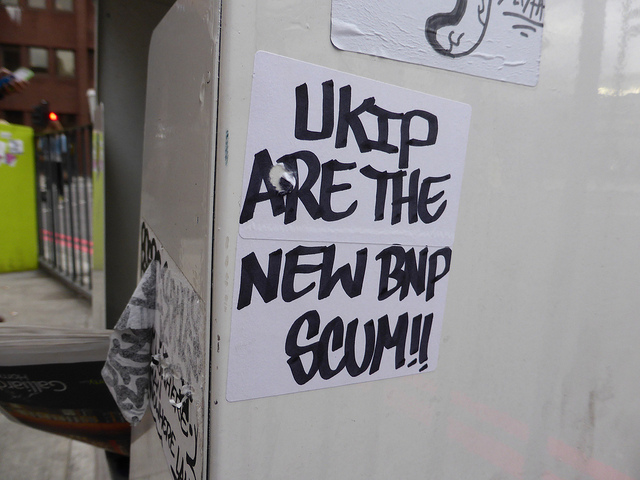

It wasn’t difficult to absorb the fallout from the implosion of the BNP and the widespread fragmentation of far-right politics in Britain. It was necessary to split the Conservative Party and swallow whole any defections. UKIP stands a better chance of breaking into the working-class base of the Labour Party. After all, there are many solidly Labour areas that would never vote Conservative. It’s much easier to mobilise such voters on the basis of nationalism than it is for market reform. This is the advantage UKIP holds over the Conservative Party.

The demise of social democracy

Since Tony Blair came to the helm of the Labour Party in 1994, itself an event with a long pre-history, going back as far as the early post-war years. It was the culmination of the struggle for the future of Labour throughout the 1980s and the stagnancy of the ‘70s. Consciously modelled on the so-called ‘Reagan Democrats’, the Blairites set out to turn the tables on the Conservative Party by playing them on their own terrain. As it was with the rise of Bill Clinton, New Labour stood for the politics of triangulation.

By now, the labour movement had been so smashed that it posed little threat to corporate interests. The kind of forces which can be driven out of a mass-party by trade unions were welcomed with open arms. Tony Blair knew he could take the working class vote for granted. It was the middle class conservative and liberal voters that he wanted to harness. Turning to polls, the party machine tested the waters for the shift it was about to make.

Not only would the support of the working class be taken for granted. So would many of the left-liberals at The Guardian, and elsewhere. It was managerial politics par excellence. The Blairites quickly threw away the commitment to nationalisation, all the while proclaiming that they were forging a ‘Third Way’ championed by the likes of Anthony Giddens, et al. At this point, Blair declared the Labour Party, for the first time in its history, a democratic socialist party.

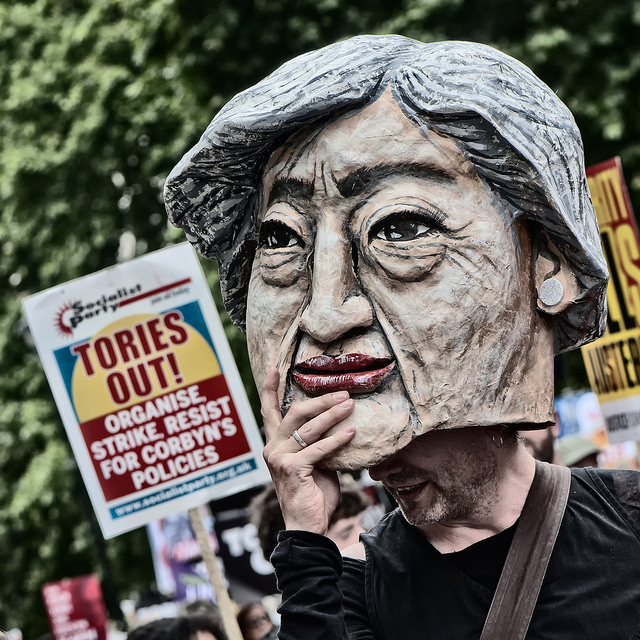

At the same time that the Labour Party was undergoing these changes, the Conservative government was entering its death spiral. After the Poll Tax demonstrations turned violent and descended into full-scale riots, the Tories decided Thatcher had to go. A million people rioted in London. Wages had reached their lowest point in years. At the same time, the Conservatives were bitterly split over the question of Europe. Out of this fallout, the UK Independence Party would emerge.

A reactionary’s revolt

In the wake of the Labour Party’s transformation, the left opposition to right-wing liberalism has been foreclosed. The aggression of nationalist populism stands outside the status quo as the only alternative and fills the only space left open. The disillusionment of Labour and Conservative supporters tend to come from a viewpoint that does not embrace social and economic liberalism. This is the strength of the appeal.

Once upon a time, the Labour Party had been the home of Euroscepticism where MPs such as Michael Foot, Dennis Skinner, and Tony Benn, took issue with the European project for its lack of democratic accountability and its managerial role in capitalist societies. It was Ted Heath, and even Margaret Thatcher, who were vocal advocates of the common market and supported integration to the hilt until finally finding the project distasteful once it began to move beyond these parameters.

It’s hard to believe today, but UKIP was first founded as a centre-left liberal party by the social democrat Alan Sked. The implosion of the Tories sent many hard-right supporters to seek out alternatives, and UKIP became one such focal point. Its Eurosceptic agenda attracted many disaffected conservatives, libertarians and nationalists. UKIP was much less adept at luring in refuges from the decline of the social democratic consensus. In the end, Alan Sked felt compelled to resign, as he saw his party become “infected by the far-right”.

The decay of the social democratic consensus and the decline of the labour movement meant that the Labour Party has ceased to serve as a progressive force in public life. Class politics has been collapsed into the question of national sovereignty: firstly, competition in the labour market, secondly, the impact of free-trade agreements. Increasingly the discourse around race has become a cultural matter. All left criticism in this time has been painted as ‘political-correctness’. It’s out of this swamp that UKIP grew, and took shape.

Last month, Nigel Farage caused a minor scandal by announcing that HIV positive migrants should be restricted from entering the UK. Farage is a cunning player. He is more than aware that he would stir outrage from the liberal commentariat. The point was to strengthen the way his supporters view him as a renegade fighting against political-correctness and multiculturalism. Farage drew out such issues at the level of disease prevention. This is how the agitator operates, and the mainstream is incapable of fending him off.

Waiting for Podemos

What do we need? Fortunately, we are not without positive models. All across Europe leftists can look to the gains of Podemos in Spain, and Syriza in Greece with admiring eyes. While not ‘perfect’, they’re the left-wing response required by six years of economic crisis, and austerity measures imposed by Berlin, Brussels, and the IMF. This is what democracy should look like.

Everywhere else, it seems right-wing populism is on the march, far more able to seize the moment, and redirect grievances against the market, than center-left parties like Labour, France’s governing Socialists, and Italy’s Partito Democratico, who may very well succeed in dismantling the country’s welfare state, in a way that Mario Monti, and his predecessor, Silvio Berlusconi, failed. Making the center-left responsible for a rightist program is the best case for neo-fascism.

There has to be a distributional battle fought within the European project. For a long time, it was fought solely by the neoliberal centre-right on the side of the ruling-classes of core economies, particularly Germany and France. The European elections produced one conclusive result: a rejection of the consensus. But in Spain this has come from a radical left position. If we want to challenge nationalist populism and the neoliberal consensus then we have lessons to learn from Podemos.

The success of Podemos comes down to its commitment to a broad-based populist strategy, appealing to ‘common sense’, even to patriotism, and capitalising enormously on the energetic grass-roots built up since 2011. Podemos emerged rapidly. and has made great gains since it was founded 100 days ago. It has gained nine MEPs in the European Parliament. It took UKIP, a leading right-wing populist party in Britain, over 15 years to gain 13 MEPs and it has jumped to 24 MEPs since 2009. The significance of the gains made by reactionary populists is that the Left has not fought hard enough.

Given the situation, in Britain, it is necessary to build a left-wing counterweight to the Labour Party. Not only does it have to fight for the social development secured after World War 2. It has to be capable of pushing for renationalisation and redistribution. Vitally, the Left has to articulate a critical narrative on the European Union and present a federal union as a radical alternative to the Tory variety of devolution. As there is no effective left opposition, this is the only way to pull together progressive forces, and mount a credible, and effective opposition so sorely missing in today’s British politics.

UKIP’s rise should be instructive, in this regard. Its anti-democratic, racist agenda is simply filling in for a left that long ago stopped prioritizing the promotion of social equality. Imagine what emphasizing such a politics, as a core political principle, might do. This is why Britain needs a new left-wing opposition party. If other European countries can do it, we can, too.

Photographs courtesy of Dauvit Alexander, European Parliament, and Julien Lagarde. Published under a Creative Commons license.

1 comment