After watching hours of CNN’s coverage of the unrest in Ferguson, I felt a desperate need to protest against the St. Louis County grand jury’s decision not to indict Officer Darren Wilson for the shooting of Mike Brown. But because there were no protests taking place nearby, I headed to a suburban theater to watch the latest installment in the Hunger Games franchise instead

It was the perfect time to see it. Whether because my far-flung “neighbors” were glued to their television sets or, more likely, because the prospect of going anywhere on the coldest night of the year was too daunting, I found myself utterly alone in the complex’s biggest auditorium. Soon, I was fantasizing that my isolation was political. Could the conservative communities nearby have warned their inhabitants not to see the picture? Was it possible that Oro Valley’s ridiculously overstaffed police department had declared a pre-emptive curfew, just in case its few people of color felt motivated to throw off their cloak of invisibility?

Although I knew these speculations were ultimately silly, I let them run their course. They spoke to my own sense of marginalization as one of the few people in my area who wasn’t contemplating the burning of police cars and chain restaurants with horror or disgust. And they reminded me as well of the heroine of the Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen, who is ripped away from the only home she has ever known to observe the wider world from a position simultaneously privileged and precarious, gradually coming to understand that her country is primed to fall apart at the seams.

As I began to watch this latest film, which covers roughly the first half of author Suzanne Collins’ third book The Mocking Jay, I couldn’t help but notice parallels between its tale and the news that I had just been watching. Like its predecessors, this installment depicts a dystopian future for the former United States in which mass media play a crucial role. It’s no exaggeration to say that Panem, the oppressive state which unites most of what’s left on American territory, has been held together by the psychological investment its inhabitants have in the Hunger Games, which serve a ritual function that echoes both the dramas of Ancient Greece and the gladiatorial combat of the Roman Empire.

That’s why, when Katniss effectively short-circuits this spectacle at the end of the second film Catching Fire, the hold which the Capitol exerts over the nation’s impoverished outlying districts rapidly starts to weaken. In the absence of the rooting interest which audiences were encouraged to cultivate during seventy-five years of Hunger Games, more and more of Panem’s people start to focus on their own problems. By living vicariously through their favorite tributes in the arena, inhabitants in the districts had managed to suppress the knowledge that their own lives were, in effect, being sacrificed for the good of the state. Now that they are forced to confront the realities of their own existence, they realize that the only way for them to improve their lot is to risk their lives with the same abandon that the tributes were forced to demonstrate.

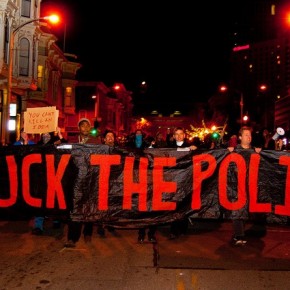

Watching the people of Ferguson take to the streets, first in the wake of Michael Brown’s shooting this past summer and again, over the past two days, in response to the grand jury’s decision, it was hard not to discern a similar process at work. Instead of being distracted by the mass media reporting on celebrities — musicians, athletes, actors and, most pertinently, the ordinary people transformed into temporary “stars” by reality television or the internet — they had decided to make their own news, declaring their refusal to continue accepting a status quo in which government operatives can kill people of color with impunity.

But this break with precedent did not succeed in rendering the media irrelevant. People who had previously been denied the opportunity to be represented on screen started to perceive themselves as actors in a double sense, making a discernible historical impact, certainly, but also playing a role before a public far exceeding their immediate acquaintance. As the protests dragged on over the past two months, this latter sense of “acting” increasingly came to the fore, sometimes threatening to become their main purpose, rather than a byproduct of collective endeavor not dependent on the presence of cameras to survive.

This shift of emphasis has been a significant hindrance to social movements since the 1960s — if not sooner — which gave us, during the infamous Democratic Convention in Chicago, the double-edged chant “The whole world is watching!” Intended to shame the forces of oppression, who were brutally beating demonstrators in the streets while the politicians met inside, it had the collateral effect of making it seem that media participation was a prerequisite for a successful action. Ever since, savvy organizers have made sure to let news organizations know “what, when and where” prior to any protest, imparting a pre-scripted air to the proceedings that would follow.

While the story arc in Mocking Jay has passed the point during which the Hunger Games themselves are taking place, we see how their impact lingers on through the interviews that host Caesar Flickerman conducts with Katniss’s ostensible love interest from The Hunger Games and Catching Fire, the painfully earnest Peeta Melark. Even the rebels ensconced deep underground in the breakaway District 13 watch these exchanges with rapt attention. Indeed, one could easily reach the conclusion that the whole country is in a state of acute media withdrawal, desperate for the sense of direction which the spectacle in the arena provided.

That is why District 13’s leadership concludes that they need Katniss Everdeen to keep the fires of revolution from dying out. Some of the new film’s most powerful sequences show how she comes to serve as its willing figurehead — after having done so inadvertently while competing in the last two Hunger Games — acting out the role of a modern-day Joan of Arc for the rebels’ cameras. We see how the need to produce compelling footage pushes her into harm’s way, captured in scenarios that seamlessly blend news coverage with propaganda.

As I reflected back on what I’d witnessed earlier that evening during CNN’s coverage of the protests in Ferguson, it was hard to shake the impression that the cameras had played a similar role in shaping the course of events. Always careful to give the impression that they were impartial bystanders to the proceedings, caught in the figurative and sometimes literal cross-fire on the Missouri town’s run-down streets, the network’s reporters nevertheless seemed to be dictating the flow of events with the way they steered viewers’ attention. Even if that was never truly the case, the seemingly insatiable need for more content, whether from street-level or overhead, surely had a significant role to play in determining who went where and when, both for the protesters and the police.

Now I realized that the parallels I was discerning only worked if I mentally edited out the obvious differences between my own reality and that of the Hunger Games. As depicted in both the books and movies, Panem is a place in which the relationship between the center and the periphery is brutally hierarchical and the scattered remnants of the former United States have been reduced to a population density more in keeping with the Dark Ages than the twenty-first century. And the mass media in this dystopian setting resemble the sort found in anti-democratic states like China or North Korea or, to a lesser degree, Western Europe during the Cold War when the only channels available to watch were typically under direct government control.

In fact, although the Hunger Games franchise is set in the future, the world it conjures feels decidedly mid-twentieth-century, as it if it were cobbled together from memories of “actually existing” totalitarianism and the science fiction that imagined how it might spread and evolve. Given the overwhelming degree of choice in contemporary American society, however circumscribed by financial limitations, and the relative weakness of the state amid the relentless war on Big Government, the situation in places like Ferguson could only be described as Hunger Games-esque by those too near-sighted to perceive these differences.

And yet, despite being constantly reminded that the United States had come “so far” since the days of lynch mobs and legal segregation, from the President on down, I couldn’t help but wonder whether the discrepancy between Katniss’s world and my own doesn’t serve to deflect attention from some disturbing truths. Even if it is not geographically confined to one place like Panem’s Capitol, the center in contemporary American society keeps taking more and more from the periphery, while giving less back in return, while poor people, especially those of color, continue to be offered up as tributes to our need to see conflict acted out on television.

Still from The Hunger Games: The Mocking Jay, Part I courtesy of Lionsgate