When I saw the coupon in my social media feed, I just had to buy the new Sleater-Kinney album at Best Buy. It’s hard to imagine a more incongruous place to procure the return of those darlings of middle-aged — and usually white — music critics. But that’s why it felt so necessary. I needed to be reminded of the world the band had warned us about.

Fittingly, when I showed up at the location closest to my house, I couldn’t even find the music section for several minutes. It seems like it has been shrinking steadily for a decade, reaching the point now where it constitutes just one shelf unit behind the also-dwindling selection of DVDs. And once I’d located the section, there wasn’t even a tab for Sleater-Kinney. I began to wonder whether the coupon hadn’t represented a bit of dark humor.

Why would I have been so gullible as to believe that a store that had never really supported independent music culture would be doing so now, when it barely sold music at all? An employee stopped to ask whether I needed help. I usually avoid assistance at all costs, believing that I should be able to find what I need without it. Since I had the coupon pulled up on my phone, I decided to make an exception. He had never heard of the band, naturally. After I’d told him that the album had just came out that day, however, he told me that it probably hadn’t been unpacked yet. Sure enough, when he went in the back, he found boxes of albums that hadn’t made their way onto the shelves. He handed me a CD from the stack of four he had carried out and hesitantly put the others on the display of new releases near the entrance, clearly uncertain whether the coupon’s existence meant that Sleater-Kinney was worthy of such prime real estate.

The whole experience reminded me of what it was like to purchase music on independent labels in the 1980s. Young people like me would go to a suburban chain outlet like Sam Goody over and over for weeks, sometimes even months, looking for a record we’d heard about from college radio or our friends. If we got up the nerve, we might inquire at the front counter, more often than not being met with a blank look that communicated a mixture of ignorance and arrogance meant to put us in our place. In my case, though, the sense of shame I felt after revealing desire for something which “normal” people simply didn’t want prevented me from even getting that far.

Feeling agitated from the body memories of those now-distant days, I exited Best Buy in order to indulge this love I was still reluctant to speak about, in the privacy of my vehicle. By the time I was a minute into No Cities To Love’s second track “Fangless,” I realized how apt my impression had been. As is true for the majority of Sleater-Kinney’s songs, it manages to sound the way only they can sound while simultaneously sounding like it’s coming from the past. And, as is the case on many of the album’s numbers, it sounds in particular as if it were coming from an alternative music fan’s understanding of the 1980s.

Songs stop and start unpredictably, their edges misaligning so dramatically that you keep snagging yourself on them onto you have listened to No Cities to Love long enough to know what’s coming. Even then, they don’t really start to cohere. But the music’s fragmentary quality never feels like the result of its being slapped together too soon. The band was apparently rehearsing in secrecy for two years before heading to the studio and it shows. If the songs refuse to settle into a groove, it’s because they aren’t supposed to.

Indeed, No Cities To Love is in some ways the band’s most unsettling work since their second album Call the Doctor. Instead of letting you be, it asks you to keep becoming someone else. Moments of conventional beauty end too soon. Sometimes the parts you want to hear again don’t repeat, or at least not the way you expect or desire. On several tracks, including “Fangless” and closing number “Fade”, it almost feels like a new song takes over more than halfway through. While it would be a fool’s errand to try to pin this aesthetic too closely to any one era, it reminds me most forcefully of the liberatory undecidedness of alternative music in the 1980s, when the rules for how to write a song in opposition to mainstream culture were still being endlessly rewritten. It was a time when almost everything was permitted and a lot went out of its way not to be easy on the ears or the head.

Others will no doubt hear echoes of different periods on the album. But one of the most likely candidates is the mid-2000s when bands like Interpol, The Rapture, Les Savy Fav and Bloc Party were themselves revisiting the 1980s. Strangely, that was the period in which Sleater-Kinney was straying from short-form songs into the acid-tinged blues that made The Woods so distinctive. For the band to be invoking that period’s particular brand of nostalgia now, in 2015, seems oddly out of step. Perhaps that’s the point, though. Tucker, Brownstein and their superb drummer Janet Weiss have long been masters of asynchrony. In a sense, their whole catalogue has advocated for a timeliness that must, by definition, be untimely.

In this regard, it’s worth reviewing the band’s history. Sleater-Kinney started out as an alternative to “alternative”, emerging from the same independent label scene in the United States’ Pacific Northwest as Nirvana and Pearl Jam, but too belatedly to catch the wave that had carried those male bands to cross-over stardom. They missed the feeding frenzy of the early 1990s, in which major labels threw a little money and lots of legalese at new artists in the hopes of striking it rich again. Instead, they embraced those aspects of the scene that the mainstream either could not or would not accommodate. It was this insistence on not making concessions to the culture industry that both established their reputation and helped keep it growing, even through the eight years that they were gone on hiatus.

The band’s very name signals this identification with what was left behind. Sleater-Kinney Road is located just outside Olympia, Washington, where co-founders Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein had attended the famously counter-cultural Evergreen State College. Most Olympia musicians eventually head up or down Interstate 5, to Seattle or Portland, once they attain a certain stature. So did Sleater-Kinney, settling in the city Brownstein would lovingly mock in her comedy television series Portlandia. But by reminding fans where they came from rather than focusing on where they were going, the band demonstrated a profoundly melancholic relation to the smaller, fiercer worldview of their Olympia circle.

Throughout the late 1990s, as one alternative rock artist after another lost their major-label contracts and a strange melange of corporate hip-hop and bubble-gum pop came to dominate record sales, Sleater-Kinney proudly carried the banner for a different approach to life and art. In retrospect, it’s no surprise that they were championed by Baby Boomer critics and fans who otherwise had little use for new music, since they communicated the appeal — some would call it perverse — of looking back with longing and regret.

Tellingly, the cover to Sleater-Kinney’s breakthrough — at least in independent-label terms — third album Dig Me Out mirrors the third album of The Kinks, The Kink Kontroversy. That record, even though it was released little more than a year after the Kinks burst on the scene, featured the mordant nostalgia of “Where Have All the Good Times Gone”, in which lyrics by The Beatles and The Rolling Stones are slyly repurposed as a commentary on the sense of belatedness that paradoxically shadows a culture obsessed with the currency of now. Sleater-Kinney couldn’t have picked a better way to telegraph their relationship to the music industry or the Riot Grrl phenomenon that Tucker and Brownstein had experienced during their time in Olympia.

Possibly the best song on Dig Me Out — and maybe even the band’s whole catalogue — is “One More Hour”, which conjures the end of Tucker and Brownstein’s romantic relationship. Although the track provides compelling evidence that their music had never been more vital, particularly in the chorus “Oh, you’ve got the darkest eyes”, which they sing together with heart-rending conviction, the sense of irreparable decline is overwhelming. You could make the case that everything that Sleater-Kinney did after that, from the intricate figures of The Hot Rock through the bluesy turn of One Beat to the brutal psychedelia of The Woods, which until recently seemed their capstone, is suffused with the aura of the afterlife, revenants sent to remind us how tenuous our hold on the present truly is.

From that perspective, No Cities To Love doesn’t seem like much more of a “comeback” than its predecessors. Maybe that’s why it doesn’t sound like the sort of record a band releases when it is ready to bask in the glow of past glory. I think that’s why the frisson I experienced buying a Sleater-Kinney album at Best Buy was almost as intense as it would have been fifteen years earlier. Yes, No Cities To Love has its elegaic moments. But they are actually less frequent than on the band’s previous albums. The studied imperfection of the songs, which succeed precisely because they don’t try too hard to convince us of their importance, invites us to return to that back catalogue, recently reissued in a lovely vinyl box set, in search of new ways to begin again. At a time when reissue culture seems more and more dominant, that is a potent gift indeed.

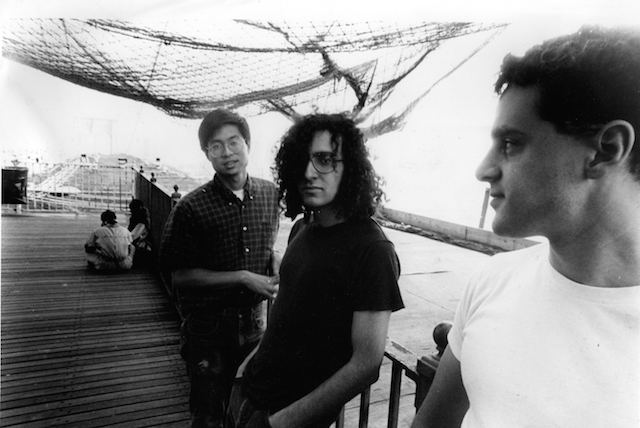

Photo by Brigitte Sire, courtesy of Sub Pop Records.