More and more, the dozen years between the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and September 11th, 2001 seem like a mirage. Although horrific conflicts took place then — in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and elsewhere — they appeared to be exceptions to an increasingly inevitable New World Order, in which peace-time problems would dominate the headlines. Military budgets were slashed throughout the developed world, especially the United States and Russia.

The trend was so readily apparent that the culture industry had to turn to fantasy and science fiction in order to generate content appealing for the bloodlust of young male consumers. Films like Independence Day, Starship Troopers, and the Lord of the Rings trilogy and games like EverQuest and Halo all entered production during this era, though some of them did not debut — probably to their financial advantage — until after the Twin Towers had fallen.

What stands out in retrospect is how, as the sight of men and women in uniform became less common, particularly throughout Europe, the hunger for clearly defined sides demanded the creation of fictional surrogates. There was nothing new about narratives in which human beings must battle other species, of course. But instead of standing in for real-world enemies, as was the case during the height of the Cold War, these inhuman antagonists instead started to serve as variables for which a solution could not yet be reckoned.

It felt like confirmation of far-right theorist Carl Schmitt’s famous argument that politics can always be reduced, in the end, to the distinction between friends and enemies. Without a clear sense of what they should be against, in the heady days when a global government almost seemed probable, a great many people suffered from existential confusion. Conspiracy theories abounded, and middle-of-the-road figures like Bill Clinton were slotted into them as arch villains. Precisely at the moment when the “peace dividend” was ready to be cashed in, the idea of war was being reinvented in order to satisfy the craving for politics as Schmitt defined them.

That’s part of the reason why, after September 11th occurred, it proved so easy for governments to ramp back up to a state of perpetual readiness akin to the Cold War. Although the flags and uniforms that had helped to sort the “good” guys from the “bad” ones during that period were no longer relevant, enough people had learned to identify their enemies with the help of markers that it was easy to revive wartime mentalities.

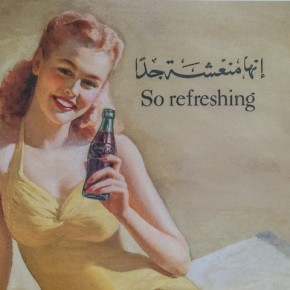

If you think about the vitriol directed at “ragheads” within the post-9/11 United States — recently revisited in the controversial Clint Eastwood film American Sniper — and the measures taken against traditional Muslim clothing for women in places like France, the impact of this newfound flexibility in deciding what constitutes a uniform will be readily apparent. Even the emphasis on items of clothing like the hooded sweatshirt in the United States, thought to be evidence of potential criminality in youth — many public schools actually banned them — bears this out.

Nearly a decade and half into this new reality, it has never been more clear that most military actions going forward will pit men and women in traditional uniforms, not against others wearing traditional uniforms, but against ostensible civilians whose “uniform” is defined by the state and its supporters rather than by those civilians themselves. Even in cases where conventional nation states are at odds, such as the eastern third of Ukraine, much of the fighting still assumes this asymmetrical character. While Vladimir Putin may ultimately decide to fully engage the Russian military in the conflict, he has so far been content to support the rebels less overtly, perhaps because he hopes that their cause will benefit from its apparent asymmetry.

From one perspective, this trend just represents a revival of the guerrilla struggles of the Cold War Era. But there is a crucial difference. Whereas such conflicts used to play out primarily in the so-called Third World, they are now inextricably bound up with everyday life in the world’s most powerful nations. Uniforms are becoming as commonplace at home as abroad. And wherever they appear, they represent a show of force by the state against those who feel and sometimes actually are stateless.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.