When Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote the first lines of The Communist Manifesto, they turned the conventional notion of haunting on its head, conjuring the “ghost”, not of something that had passed away, but of something that had not yet come to pass. Since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, though, this has changed decisively. The world is haunted instead by the communism that was — and wasn’t.

The failures of the Soviet Union and every other nation that made Marx and Engels into founding fathers are so painfully obvious that even the most easily deluded leftist feel compelled to acknowledged them to some degree. And it is equally clear that what remains of actually existing communism in mainland China and Vietnam today is little more than a front for a perverse amalgam of cronyism and state capitalism. Yet despite the preponderance of evidence that communism has not and presumably can not work in a world where the laws of the marketplace hold sway, hundreds of millions of people still feel a twinge of nostalgia when they recall the time when the First World was still offset by the Second.

Frequently, this nostalgia has only a tenuous connection to the ideology of communism, fixating instead on the ways in which everyday life in those regimes — even when it was brutally difficult to bear — differed from the globalized frenzy of our own era. But there are also plenty of folks who look upon the diminishing financial and social returns experienced by the so-called “99%” and ask themselves whether the theory of communism might not be valid despite all of the misguided attempts to put it into practice.

The further we get from the atrocities committed under Stalin and Mao, not to mention the more subtle outrages of bureaucratic totalitarianism, this latter position seems more reasonable. When the people you see suffering are primarily victims of an increasingly unfettered capitalism, it’s not that hard to conclude that the best way to fight back is the only ideology that was ever strong enough to make it compromise.

This is not to imply that a meaningful communist insurgency is about to take hold in places like Germany. Right-wing populism seems a far more likely candidate at present, because it mobilizes parochial anxieties in an era of dwindling resources. Whatever its ideological inflection, internationalism strikes many have-nots as a Trojan horse for the haves. But there are other dimensions to communism more amenable to the present conjuncture.

First and foremost, there is its value as a weapon against prevaricators. For a communist, capitalism is the enemy plain and simple, regardless of how the state intervenes in its workings. Secondly, there is its willingness to celebrate all forms of labor, including those in danger of being rendered obsolete by technology. And, finally, there is communism’s promotion of solidarity for the sake of solidarity, which looks more and more attractive in the face of the atomization of postmodern existence.

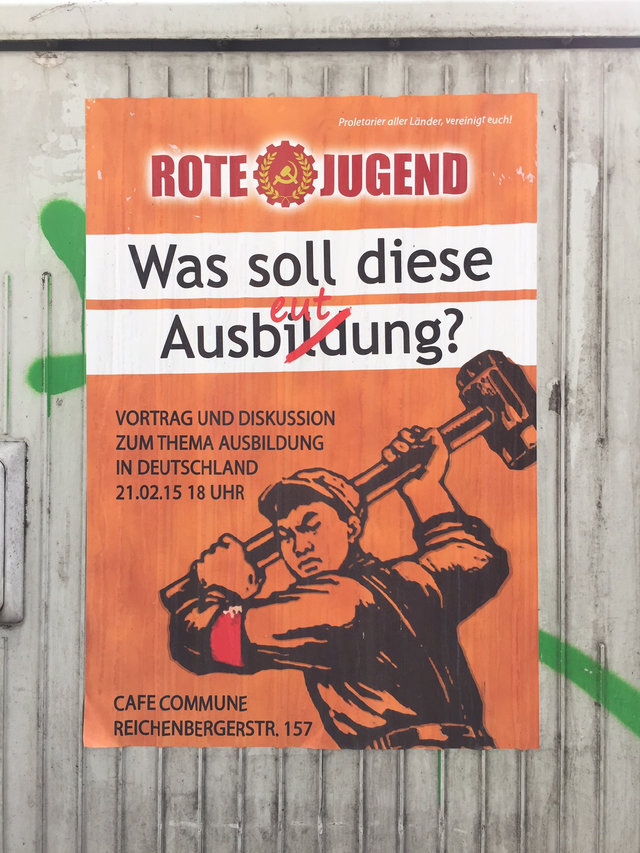

The poster seen in the lead image here, for the “Red Youth” movement making its presence felt in the former East Germany, is a fine example. The question it poses, which crosses out the word for vocational training, Ausbildung, with the word for exploitation, Ausbeutung, implies that the educational system is set up to produce workers who won’t or can’t challenge their precarity instead of ones who will have what it takes to organize resistance to the owning class. What is most striking, however, is the use of a Chinese graphic, probably dating back to the Cultural Revolution, to symbolically hammer home this point.

At a time when resentment towards “foreign” laborers is growing rapidly and suspicion of mainland China’s imperial ambitions is also on the rise, invoking internationalism in this manner could be a risky move. But the creator of the poster clearly felt that the power of this classic communist iconography outweighed any disadvantages.

Perhaps this has to do with the fact that mentioning China was taboo during the last quarter-century of East Germany’s existence. If you or your parents grew up as Ossis, you wouldn’t have experienced the Mao cult that partially hijacked the student movement in the West. Even so, the nostalgia for a time when communism wasn’t yet a ghost of its former self is significant.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.