“When sorrows come, they come not single spies. But in battalions,” Shakespeare once wrote. And so it has been in Britain this week, as massacres in Malaya and Malawi, and dark deeds during Northern Ireland’s Troubles appeared to be catching up with the establishment.

While historical allegations of abuse, murder and torture crop up fairly regularly, it is not often that three legal challenges to historical cases of abuse and murder arrive in a single week – and certainly not with one case having the potential to tip circumstances in the favour of the victims.

The first and most important is the case of Batang Kali.

In December 1948, Malaya was British protectorate and its citizens – whom the UK were trying to separate from a Communist insurgency – were British subjects.

On the 12th of that month, a 16-man patrol from the Scots Guards entered the tiny Malayan hamlet of Batang Kali. When they left, 24 unarmed villagers were dead.

The killings have been obscured and reinterpreted by the establishment ever since, with two criminal investigations being scuppered by uncooperative UK officials.

In 1969, the case again made headlines, when several of the soldiers present on the day stated that they had been ordered to carry out the massacre.

Of the various excuses used by the government over the decades, one of the most enduring is that given the passage of time, there is little to be gained by opening up a case better consigned to history.

The fact that the Batang Kali case – often referred to as Britain’s My Lai – has been accepted for a review, is important in itself.

If a precedent is set that there is no “vanishing point” at which legacy cases cease to be worth pursuing – that justice, in effect, does not have a sell by date – than the knock on effects could be massive.

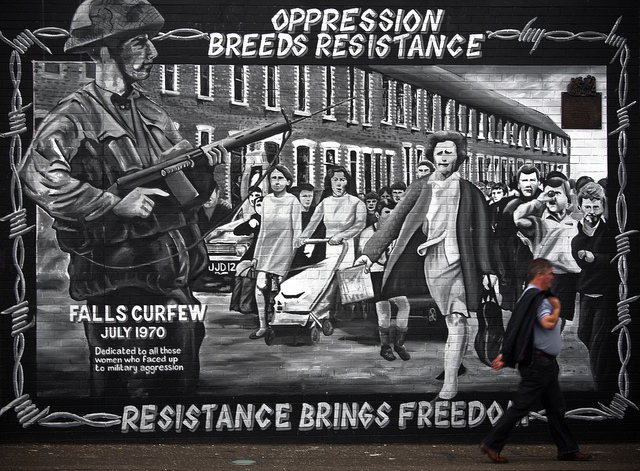

Which brings us to Northern Ireland.

A number of NGO’s based in or concerned with the occupation era hope that the Malaya case will bolster their own.

Yasmine Ahmed, director of Right Watch UK told The Guardian, “The outcome of this case will have considerable implications in Northern Ireland, where many of the deaths that occurred during the Troubles happened before the enactment of the Human Rights Act in 1998.”

A spokeswoman for the Derry-based, human rights-focused Pat Finucane Centre told the paper: “Dealing with the past, whether through inquests or investigations, continues to be a battleground where the UK government seeks to deny families the right to truth.”

“The Batang Kali massacre is proof that the past will always come back to haunt us if it isn’t dealt with.”

This, in a week which offered an insight into the shadowy world of UK operations against the IRA – a cut-throat business by all accounts as one ex-informer, who survived two attempts by the dissident Republican group to take his life, spoke out about the British habit of betraying their collaborators.

Speaking ahead of another inquiry into the security services conduct during the conflict, Marty McFarland said: “It’s my understanding that for 15 years, first the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and later the Police Service in Northern Ireland (PSNI), sat on evidence that could have led to the arrest of both men.

“I have consistently said I would go as an eyewitness, naming these two people as the ‘guards’ that held me in the flat in Twinbrook before I was to be tortured and then shot dead.”

“I also know for a fact that for 15 years, the RUC and then the PSNI failed to make it public that there was fingerprint and DNA evidence from that flat in Twinbrook which belonged to these two men.”

Britain’s history of African colonialism is proving no less troublesome this week.

While the atrocities of the Kenyan Mau Mau insurgency are in news relatively regularly it is the 1950s decolonisation struggle in Nyasaland – today’s Malawi – which has reared its head this week.

Relatives of protesters killed in 1959 by British colonial forces during Operation Sunrise in Nyasaland have pledged their determination to seek justice.

The operation was a British effort to quell anti-colonial activism and involved the snatching, Gestapo-style, of 350 prominent activist by a mix of local police and military units.

The snatch operation culminated in 51 deaths.

In light of the progress made by the Mau Mau victims, the Malawian campaigners have promised to push the current Malawian government to put pressure on an increasingly harassed British government.

With the Chilcot Inquiry delayed (again), the controversy over the British-owned, US military occupied Chagos Islands bubbling along, and a whole layer of cases from Iraq waiting to pick up where the recent Al-Sweady inquiry left off, there is unlikely to be a let up for Britain’s excuse-makers in chief at any point in the near future.

Photographs courtesy of Eduardo Fonseca Arraes, and unkown. Published under a Creative Commons license.