At a time when the word “fascism” is being thrown around with increasing carelessness, on both the Right and Left, the fight against it is plagued by confusion. Most people, regardless of their ideological position, adhere to the belief that being a fascist requires some form of totalitarian behavior. But the role of the state in that behavior is no longer taken for granted.

Indeed, the terror mongers in ISIS, like their predecessors in al-Qaeda, though they do not yet preside over a functioning state are frequently described as fascists. And the term is bandied about in more intimate contexts as well, to the point where it has come to seem little more than a synonym for “bully”. Nevertheless, even the most far-flung uses of the term are still grounded to a degree in images identified with Nazi Germany: soldiers moving in lock step, propaganda used to suppress dissent, the industrialization of persecution.

Despite Rush Limbaugh’s profligate use of the term “Feminazi”, fascism is also associated with a brand of extreme patriarchy, in which power is expressed through traits considered to be male, such as aggression and a hardening against feeling. Certainly, this understanding applies today in the mobilization against so-called Islamo-fascism, which is excoriated for its treatment of women.

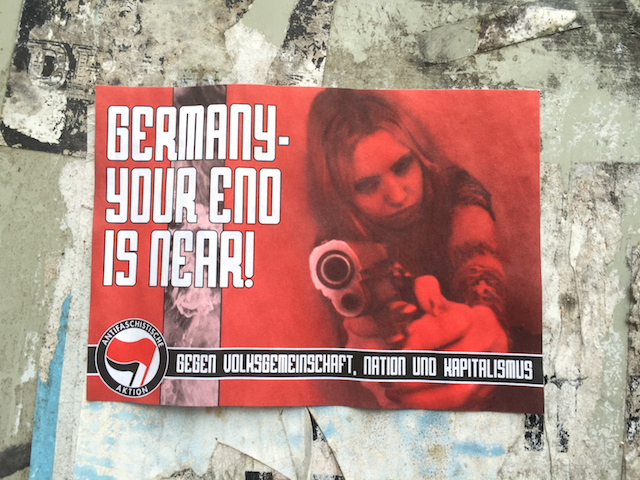

These posters for the contemporary German anti-fascist movement — or Antifa, as it is commonly called — must be interpreted in relation to this background. On the one hand, they implicitly seek to reassert the traditional leftist definition of fascism, as a toxic alliance between state power and capitalism facilitated by fake populism. On the other, they seek to recontextualize the struggle against this political oppression in terms of gender.

This rhetorical strategy is not without problems. From one perspective, it partakes of male fantasy — the tough punk gal with a cigarette and her counterpart with a revolver aren’t that far removed from the cross-dressing role play seen in certain kinds of pornography — in a way that calls that gendering of struggle into question. And it is also worth asking whether it makes sense to make “fascism” one’s primary target, if its definition has become so muddy.

At the same time, though, there’s something to be said for reminding us that, for all of the superficial progress made by women in recent decades, the world is still largely ruled by men. Maybe we have a harder time figuring out how and why the nation still matters under the hegemony of transnational corporations. But there’s no denying that men still make more money and decisions than women.

Moreover, when women do make their way, against discouraging odds, into positions of real power — Margaret Thatcher and Angela Merkel come to mind — it is usually because they have demonstrated a willingness to defend the status quo against threats from the subaltern. When women are still the property of men, in effect, or at least treated that way, as continues to be the case far too frequently these days, the logic of presenting all attempts to undo the prevailing social order as a war on patriarchy is hard to argue with. People may laugh these days when aging hippies talk about fighting The Man, but that doesn’t mean the impulse is misdirected.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.