The Etonian scribbler James Delingpole likes to describe the Greens as watermelons: green on the outside, red on the inside. Today’s Green Party is well to the Left of the trilateral consensus, and its policies have shocked many minds ensnared by conventional wisdom. But it wasn’t always the case. All parties are coalitions, and coalitions mutate over time.

The Greens emerged from the experimental politics of the 1970s, when environmentalism straddled conservative and radical tendencies. It’s probably no coincidence that the modern Green movement comes out of the same period as the energy crises and the oil embargo. A messianic sense of mission had captured the energies of the environmentalist movement just as it had the resurgent forces of reaction.

The founder of the party’s ancestor PEOPLE was a former Conservative councillor, Tony Whittaker, and his wife, Lesley, who had been moved by the words of the American Malthusian Paul Ehrlich in a Playboy interview. Tony and Lesley Whittaker became convinced that the collapse of society was imminent. This was while English reactionaries like Keith Joseph were enthralled by apocalyptic fantasies of the decline of “human stock,” as the poor outbreed the rich, against out-of-control stagflation.

Common Ruin

The first members of PEOPLE came from the petit-bourgeoisie, precisely professionals and small-scale entrepreneurs. Simultaneously it won the support of Teddy Goldsmith, the elder brother of corporate raider James Goldsmith, and uncle to Tory MP Zac Goldsmith, who had earlier helped to found Survival International. The party machinery was dominated by what was once described as “conservative anarchists”, those who viewed state centralisation and industrialisation with disdain.

The programme was defined by Teddy Goldsmith’s writings – particularly as outlined in A Blueprint for Survival – which envisioned a small-is-beautiful society, where an organic harmony is maintained by decentralisation. The reduction of the population was preferable to ensure small communities, the scale would allow greater levels of self-fulfillment, as well as make it easier to enforce moral codes and maintain traditional models of family life. The Malthusian commitment to reducing the population would remain a part of the Green programme until the 1990s.

The Whittakers led the charge for a zero-growth economy, taking issue with the infinite-growth paradigm lying at the core of capitalism and socialism. Not only did they want less growth, if not no growth at all, the Whittakers were pushing for a complete ban on immigration and financial incentives for voluntary repatriation (a policy since taken up by the BNP). When it came to education policy the Whittakers wanted to reduce the school leaving age and encourage children to go into apprenticeships rather than higher education.

This is far from the egalitarian mission of the traditional Left, which has long envisioned a new social order of cornucopian splendour. Rightly, Karl Marx had lambasted John Malthus as a bourgeois sophist for imposing austere conditions on the masses. It was a category error, taking the symptom for the disease itself. The mode of economic development is what sets limits on the population and defines the pressure it faces. Nearly a century on, the first environmentalist party in Britain was ready to take a decisive left turn.

The 1974 election was a major let down for the fledging party, but it would ultimately lead them into the next of their development. Simultaneously Keith Joseph had lost his hopes of one day leading the Conservative Party. He had articulated the monetarist case against the morass of the Heath government, but then he made the mistake of giving a speech in which he advocated eugenics against the poor. This cleared the ground for Margaret Thatcher to challenge Ted Heath the following year.

The early formation of PEOPLE began to expand as radical leftists flooded its ranks and this trend eventuated in PEOPLE being superseded by the Ecology Party. The eco-socialist influx continued as the party made its first electoral gains in 1976. The party which had once argued against immigration would become embedded in anti-racist politics and the anti-apartheid boycott campaign. The establishment of a sustainable economy was becoming a core issue on the Left.

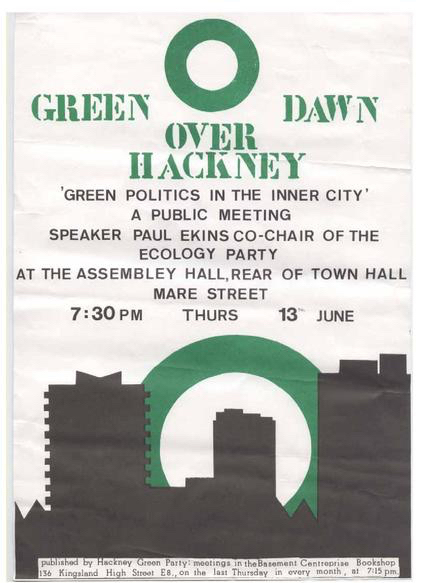

Finally in 1985 the Green Party, as we know it today, was born out of an exercise in rebranding. The Hackney wing of the Ecology Party feared the Liberals might beat them to forming a Green Party, so they quickly changed their name to outmanoeuvre them. The new brand worked, at first, as the Greens managed to mobilise over 2 million voters at the 1989 European elections. The Greens were now campaigning against the Poll Tax, while Neil Kinnock was trying to make peace with Thatcherism.

Automatic Collapse

It looks like a natural transition, in retrospect, as the expansion of capitalism is only possible within certain parameters. The environment is a major part of this picture, just in terms of resource extraction, pollution, deforestation, let alone the role of industry in bringing about climate change. Any capitalist framework, no matter how social democratic, requires endless growth. David Harvey specifies a minimum of 3% compound growth forever. It’s easy to see this dynamic running up against the natural limits of the eco-system.

As Rosa Luxemburg theorised, the momentum of capitalist development needs ‘virgin lands’ of non-capitalist societies, the resources of which it could harvest in its endless bid for capital accumulation. Yet the expansion of capitalism by empire could bring the system to its demise. As Luxemburg saw it, as capitalism becomes a global totality it would eventually exhaust its own capacity to reproduce itself. Her Leninist opponents would describe this, inaccurately, as a theory of ‘automatic collapse’.

Except for a few scattered non-capitalist pockets, we now live in a near global capitalist economy and the system seems implacably resilient. Even in the midst of an international financial crisis the long-awaited revolutionary situation has not emerged – the ‘final crisis’ still eludes the Left. All the while the economic superpowers appear to be running towards a precipice in human history. Many forces on the Right have now turned to climate change denial precisely because any alternative to this system will necessarily involve planning. The Left faces a tremendous task, and the race is on.

Photographs courtesy of Wikimedia and Nick Saltmarsh. Published under a Creative Commons license.