Ever since the first Snowden leaks in 2013, something strange has been happening in Germany. On the one hand, Germans were shocked by how ruthless the US was, going so far as to tap Angela Merkel’s phone. On the other, the government’s response was incredibly subdued. Of course, there were some publicized angry calls to Obama, and the BND reduced its cooperation with the NSA. But that was it.

Instead of leading to a real crisis in government, or at least in transatlantic relations, the German government was able to cast itself in the role of innocent victim, standing up to the American bully, with nothing but a few symbolic gestures. If that was not enough to placate the public in time for the federal elections in 2013, Merkel could point to the talks already underway with Washington about a planned “no-spy-agreement,” which would end this unsavory breach of trust ‘between friends.’

Nobody expected that the Chancellor would be able to sit out the spying scandal this easily. Something about this was just not right, and would not be corrected overnight. For the last two years, many Germans assumed that something new would yet come to light, which would blow the issue wide open, as it should have been, in 2013. Last month, it finally happened.

First, Spiegel reported that as part of its collaboration with the NSA, the BND had turned over data to the NSA that it had collected for many years, on European and German companies, most notably the European defense company Airbus, as well as on government officials – in brazen violation of an agreement by the US not to use the BND to spy on German citizens.

All this, we are expected to believe, was only discovered in an internal probe in 2013, but was kept from the public, and just recently made it up the chain of command to the Chancellery. The Merkel government, tasked with oversight of the secret service, either failed to notice, and stop this illegal spying, or – as appears to be increasingly likely – was basically fine with it.

Finally, we have a real ‘scandal’. This one will be much harder to control. As Angela Merkel tries to answer the eternal questions of “Who knew what and when did they know it?”, her coalition partners, the center-left Social Democrats, discovered that finally they have hit on an issue which could really hurt her.

The SPD have been aided by another recent revelation which – if you were not totally cynical about Merkel’s intentions already – which could be even more damaging. In 2013, the government reported that it had received an “offer” by the US for an agreement which would end the type of warrantless spying on German citizens that had just come to light. As it now turns out, however, they were lying.

A series of leaked emails between German officials and American diplomats reveal not only that no offer of such an agreement was ever made, but that the US had already rebuked the idea – which did not stop the German government from pretending otherwise in public. The following email message, from the US embassy, to Christoph Heusgen, an advisor to Merkel, sums up the dismal affair:

“Christoph, we both know that it will be a big challenge (and maybe even impossible) to keep the public debate under control, but we should not say things which will make it even more difficult to explain and to deal with potential new revelations, don’t you think?”

The letter was sent in July 2013, two months before federal elections, and right after the German government had declared that Washington had offered an agreement to stop spying. It not only shows Merkel manipulating the German public – but also her weakness and unwillingness to really challenge the Americans. At a time when the German government expressed rightful indignation, and said it would stand up for the rights of its citizens, it was actually chatting with its US colleagues about how best to “keep the public debate under control.”

Given all this, is it any wonder, that more and more Germans distrust their longtime ally, that anti-American sentiments are on the rise, and that when it comes to the crisis in Ukraine, a large part of the German public is ready to see Washington as an aggressor, not a defender of freedom and democracy? Is it true that, as Max Fisher writes in this otherwise kind of shallow piece, “bashing the Americans makes for great politics in Germany”?

If it was, why is the government – even after the recent revelations – still proudly claiming that the relationship with the US is as perfect as ever? And why, if “bashing the Americans” is supposedly so popular, is the German government not attacked more harshly in the media for its unwillingness to confront the US?

To explain this paradox, it is necessary to understand just how central the relationship to the US is to German political identity. Of course, no country in the world has a normal relationship with America – it isn’t just any country, after all. But the Federal Republic was founded on friendship and deep ties to America. It would be silly to suggest that this was the result or a remnant of military occupation, or merely a reaction to the threat of the Soviet Union. It was much more: a choice made by generation after generation, and a positive vision of creating a nation that would be part of the West. Ever since, atlanticism has been the ideology of West German political elites – as well as, stripped of its more immediate political or military connotations, an expression of popular desire to live in a more liberal and modern country.

One person who understands this well is Heinrich Winkler, an historian who specializes in the kind of sweeping histories that cannot help but be swept up in national self-mythologizing. Take, for example, the cover of the last installment of his monumental History of the West, covering the time from the end of the Cold War to the present: The flags of the transatlantic community, triumphantly flying over the modern glass-dome of the Reichstag.

It is a powerful image, which for Germans of a certain age and disposition unleash a torrent of triumphant emotions. It stands for a modern Germany which has finally arrived, after its Long Road West (the title of Winkler’s history of Germany), in the bosom of liberal democracy. As much as the German flag is hidden in the background, it is a deeply nationalist image, a celebration of contemporary Germany as stable, modern, and safely embedded in the international order.

The German Sonderweg, it suggests, the ill-fated attempt to find a path to modernity different from “Western” liberalism and parliamentary democracy, is finally over. In its worst forms, it is a narrative that can turn chauvinistic and self-conglaturatory – the depths of the darkness which has been overcome, like in the conversion narrative of a born-again Christian obsessed with his past sins, only serving to make the present achievement more perfect, more distinguishing, more to be proud of.

It is a national myth that values free enterprise and democracy as much as the Americans, but oddly couples them not with an exciting vision of “new frontiers” but with notions of stability and security – which maybe explains why Germany is able to resume its position as European hegemon in the guise of a risk-averse penny pincher, while at the same time remaining deeply afraid of the kind of military power and adventurism favored by the US.

It is not difficult to point out problems with this Teutonic version of the “end-of-history”-narrative. For instance, it tends to paper over the fact that for much of German history, at least since the Second Reich, it was the working class and the quite illiberal SPD which struggled for democracy and then later created Germany’s first republic – in other words, that democracy was always deeply connected with socialist aspirations. But that is just historical nitpicking.

There is no doubt that it is hard to argue with the success of the Federal Republic. And this success, from the very beginning, was based on Adenauer’s program of Westbindung, the attempt to integrate Germany into the Western alliance – be it militarily into NATO, economically into the common market with France, or politically and culturally by opening up to American influences.

Under the pressure of the Cold War, Western integration became bipartisan, deeply institutionalized, and one of the central tenets of Germany’s raison d’etat.

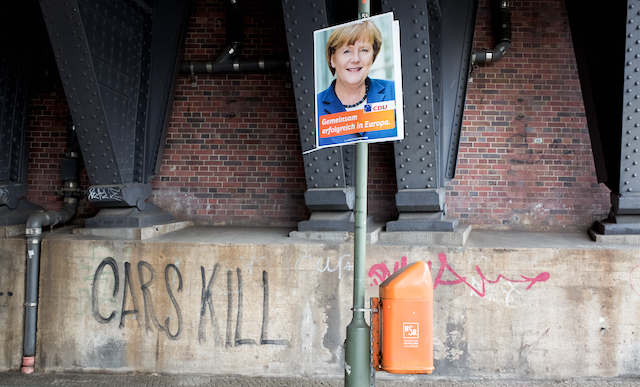

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit