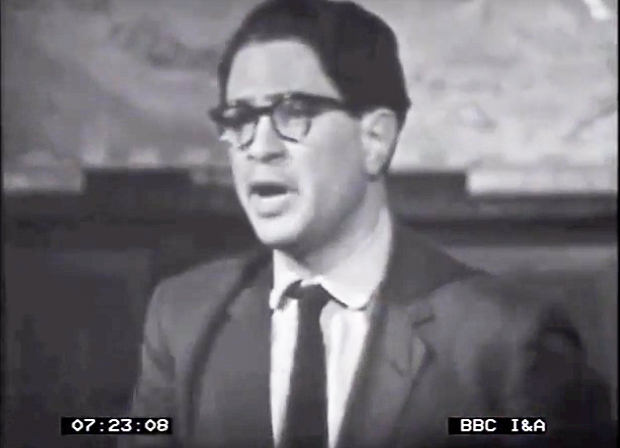

These days the name Miliband is most associated in the popular mind with the young wonks currently overseeing the bumbling demise of the British Labour Party. But there was a time not so long ago that Miliband was a name to conjure with. Ralph Miliband was one the leading lights of postwar British Marxism. He was a fighter of good fights, whether defending a reasonable and humanistic brand of Marxist theory or in standing up for the rights of radical students at the LSE in the 1960s (whereby he compromised his own position there).

There is certainly something appropriate about Verso’s reissuing of some of Miliband’s most important essays. Originally published in 1983 under the title Class Power and State Power, this new edition bears the updated title Class War Conservatism and is, like its predecessor, eminently well-timed. In these days when the tide of Marxist theory has ebbed and when the Labour Party has shown itself incapable of turfing out the dismal mediocrity that is David Cameron and his cohort, it is perhaps worthwhile to cast an eye back to an earlier era.

From the perspective of the left, the decade of the 1960s was a remarkable time. The death of Stalin and Khrushchev’s secret speech at the 20th Party Congress of the CPSU (the content of which became common knowledge in the summer of 1956) created hopes, however fleeting, that the long nightmare of repression in the Soviet Union might be coming to an end. But within months these hopes were rudely crushed, as Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest to crush the nascent Hungarian revolution.

For many on this left this was a time of great, if very much belated, disillusionment. Yet it also created a space for new intellectual developments. In West Germany, where the proximity of the GDR had long previously extinguished most of the misplaced idealism about Stalinism, the work of unorthodox Marxists such as Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse began to be taken up by a new generation of scholars and activists who would build it into the radicalism of the extra-parliamentary opposition. In France, the nascent framework of structuralism was built into a new, scientifically oriented interpretation of Marxism in the work of Louis Althusser, Etienne Balibar, Nicos Poulantzas, and others.

It is tempting to look at the 1960s in Great Britain as something of a golden era. There was renewed prosperity after the austere 1950s. For the radical left in Great Britain, the year 1956 had been a watershed. The Soviet invasion of Hungary had dealt a heavy blow to the CPGB, extinguishing in all but the most one-eyed ideologues any shred of credibility in Soviet communism. At the same time, the intervention of British and French forces in the Suez crisis constituted a start reminder that the era of European imperialism had not yet come to an end.

The second half of the 1950s had seen significant intellectual ferment on the left. The disintegration of the Communist Party Historians Group allowed a number of important scholars (Eric Hobsbawm, E. P. Thompson, John Saville, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Victor Kiernan, and others) to pursue historical study and writing freed from the yoke of communist ideological orthodoxy. Thompson and Hill paved the path of their departure from the CPGB by initiating publication of The Reasoner, a journal devoted to open criticism of the Communist Party.

After their exit from the party, the journal, rechristened The New Reasoner, forged ties with the Universities and Left Review, whose editorial board and readership with based predominantly in the scholarly institutions of Oxford and London. In 1960 the journals merged to form the New Left Review. Under the editorship of Stuart Hall (replaced in 1962 by Perry Anderson), the NLR became the primary locus for a thoroughgoing re-evaluation of Marxism in view of the political bankruptcy of both Soviet communism and the Gaitskellite Labour Party.

Ralph Miliband would become a major voice in this reconsideration and reconfiguration of British Marxism. He was born in Brussels in 1924, the son of Polish Jews who emigrated after the First World War. In his youth he was drawn (as his father had been before him) to Zionist socialism, joining the local chapter of the Hashomer Hatzair at the age of 15. A year later, Belgium was invaded by the Nazis and his family fled, with Miliband and his father catching the last boat out of Ostend for Great Britain.

Miliband adjusted well to his new environment, completing secondary school and university and eventually winning a place at the London School of Economics. In those days, the LSE had not yet become the bastion of neoliberalism that it is today, and the moderate, humanistic socialist Harold Laski was the leading figure. Miliband volunteered for the British Navy at the beginning of 1942 and his service disrupted his studies until 1946. He graduated from the LSE with a first class degree in 1947. In 1956, Miliband completed his doctorate with a thesis on “Popular Thought in the French Revolution” and received an assistant lectureship at the LSE.

By this time, Miliband’s socialism had lost its Zionist component. He joined the Labour Party in 1951, gravitating, faut de mieux, to the Bevanite wing. He became associated with the editorial circle of the New Reasoner, the politics of the ex-communists and Popular Front veterans jibing with Miliband’s youthful experiences in the continental left. When unifications talks got underway between the New Reasoners and the “culturalist” Marxists of the ULR, Miliband was vocally opposed, arguing that compressing the two groups into one journal would dilute the politics of both through compromise and evasion.

This was probably a legitimate concern, the consequences of which were at least in part avoided by the eventual departure of some (like E.P. Thompson who didn’t fit in). In any case, as Stuart Hall would later note, the merger was a necessity, as neither journal could have survived on its own for much longer. Miliband too did not fit in to the more cultural orientation of the NLR, and in light of this it is not surprising to find that in Stuart Hall’s retrospective on the New Left and the foundation of the NLR, Miliband’s name is never mentioned.

Both in the 1960s and later, Miliband represented a sort of middle ground in British Marxism between the heavily theoretical approach of Anderson, Nairn, and their colleagues at the NLR and the pragmatic humanism of historians like E.P. Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm. His first book, Parliamentary Socialism, was a Marxist critique of the Labour Party’s failure to pursue a sufficiently radical politics, very much in keeping with Miliband’s on the far left of the Bevanites. His analysis was very much in terms of concrete issues, an approach which would characterize his writing throughout his life.

Miliband’s position was one of disaffection, both with the Labour Party (which he left in the mid-1960s) and with the New Left. His critical position toward the latter took concrete form when, in 1964, he founded the Socialist Register with fellow NLR refugee John Saville. By the late 1960s, Miliband had established himself as a passionate and incisive thinker. His writings carried increasing weight within leftist circles and he stood on the cusp of breaking out into broader realms of political theory. It is at this point in his career that Class War Conservatism takes up the story.

Ralph Miliband screenshot courtesy of YouTube/BBC. All rights reserved.