From the conclusion of the Aden Emergency in 1967, to the end of the Cold War, southern Yemen was known as the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, and ruled by a Stalinist Politburo in Aden. Its ambitious domestic experiments, and Trotskyist foreign policies, were a constant headache for both its monarchical neighbours, and the nascent dictatorship of Ali Abdullah Saleh.

The PDRY played a significant role in three wars: the Dhofar Rebellion in Oman, border clashes with Saudi Arabia in 1969 and 1973, and the National Democratic Front Rebellion in North Yemen in 1976. Its defeats in these conflicts, and inability to move towards substantive democracy, is what led to the downfall of hardline President Abdul Fattah Ismail, and the ascendancy of reformists like Ali Nasser Muhammad, and Ali Salim al-Beidh.

It is difficult to understand the appeal of South Yemeni nationalism. After all, much of the PDRY’s existence was spent backing insurrectionists that were soundly defeated, and Ismail’s policies were so crudely materialist that in 1978, the Brezhnev Politburo welcomed his resignation from the presidency, and the newly-created Yemen Socialist Party. Major Communist powers found his unwillingness to stray from principles of scientific socialism, and refusal to even consider detente with the Gulf monarchies, to be a liability. These excesses defined such a large part of the PDRY’s history that nostalgia for it seems nonsensical.

Of course, the PDRY is similar to the Soviet Union in that post-socialist nationalism has more to do with cultural memory than actual political realities. It is widely acknowledged in South Yemen that the PDRY was brutally repressive, and that for much of its existence, Ismail ruled it with an iron fist. Still, the PDRY continues to mean something, and its legacy has been recently politicized for three primary reasons.

The first is that there is intense bitterness over the conditions for unification with Saleh’s Yemen Arab Republic, which already led to civil war once in 1994. Sana’a imposed massively unpopular policies in the South. Readers will find many of them familiar to those implemented in the former Soviet bloc.

Subsidies were removed. Currency was devalued. The public sector was gutted with dire consequences for housing, health, and education. Electricity and water networks were privatized, and then quickly neglected. Pensions were either reduced or dismantled, plunging many former state employees into poverty. Unification also led to the further empowerment of Northern elites, who were able to gain a monopoly on property, university places, skilled labour positions, and important industries like oil and tourism.

The second is that Saleh moved to implement cultural policies in the South that he had previously used to neutralize dissent in the North. Saleh’s approach was to mediate amongst various elites in a weak state, with particular emphasis placed on empowering tribal and religious reactionaries in order to control leaders accustomed to significant autonomy.

Saleh continues to insist that this was necessary to manage the various divisions in Yemeni society, once referring to his approach as “dancing on the heads of snakes.” The quote has been adopted with some fascination by mainstream analysts, who see it as strangely Machiavellian, with often little challenge to its implicit claim that Yemen is inherently unstable.

The reality is that Saleh sought to preserve his rule by disrupting a viable national consensus, and skillfully prevented too much power from accumulating in any one area of the country, where it could then be used to mount a significant challenge to Sana’ani hegemony.

Part of this approach has meant sanctioning the distribution of militantly Sunni Wahhabi rhetoric and orthopraxy. This move was designed to divert Yemenis away from discussions of social and economic governance, and towards cultural politics dominated by mainstream Islamists like the Yemeni Muslim Brotherhood. It has occurred to the immense consternation of Southern Yemeni nationalists, who often argue that problems like child marriage, and violent social enforcement of the burqa, became far more widespread after unification. Saleh fanned many of these practices to fragment a society that may otherwise have revolted against him, with obvious consequences for current trends of religious militancy in the country.

Support for the PDRY reflects a desire for stability in an extremely unstable era. Southern nationalism shouldn’t be mistaken for a yearning to fall back on Ismail’s socialist militancy. Rather, since 1994, nationalism has steadily become an increasingly important articulation of various grievances in local society, broadly understood as a consequence of centralized Northern control under Saleh. Southern nationalism is a rebellion against everything from social policing of the burqa, to housing shortages in Aden. Interestingly, despite its totalitarianism, the PDRY has become a symbol of hope in hopeless times.

As a result of the profound difficulties that Southern Yemenis have faced over the past 25 years, the PDRY is now fondly remembered for having a degree of redistribution, state protection, and economic stability in an era which seems to regard those desires as novelties. Its oppressiveness was unquestionable, but there is a reason why its memory has dominated the protest movements that have surged across South Yemen since 2007, when protests by retired military officers seeking their pensions developed into a general uprising.

When the PDRY existed, it provided tangible material gains for its citizens, and also gave them a sense of pride for surviving the violence of the Aden Emergency with a state capitalist alternative to the deeply authoritarian and monarchical varieties of capitalism that were establishing themselves on the Arabian Peninsula. The immense trauma of recent events has redeemed it somewhat, although there is little reason to believe that the coalition of post-2007 activists, leaders, and Popular Committees known as Al-Hirak (commonly referred to as “the Southern Movement” in Yemen) will move to recreate the PDRY in all its aspects.

Al-Hirak has numerous views on independence from the North. Some press for it outright, while others push for local autonomy, and still others desire a highly federalized model similar to the canton system in Switzerland. The plurality of views is fascinating, given that they are unified by nostalgia for a state that centrally planned all functions in Aden, and only began to include forces apart from Ismail’s factions in the National Liberation Front after threats to his power began to coalesce in 1978. Given that this current war is affecting Al-Hirak’s strategic calculus in unpredictable ways, it will be some time before it is clear which of these three positions will gain primacy in the movement. Regardless, post-socialist nationalism will continue to be an important force in the country, and its dominance in South Yemen may anticipate the PDRY’s legacy reverberating elsewhere on the Arabian Peninsula.

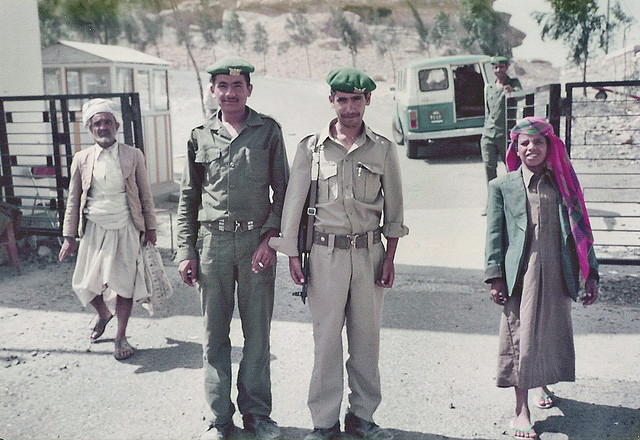

Photograph courtesy of Gareth Williams. and AJTalk. Published under a Creative Commons license.