Cambridge historian Richard J. Evans is the most eminent scholar of the Third Reich and the Holocaust writing in the English language today. He has to his credit numerous notable books, including works on the social and political history of Germany in the 19th and 20th centuries, significant contributions to the study of the historiography of modern Germany. Evans’ magisterial three volume history of Nazi Germany will be the state of the art for decades to come.

Evans has, moreover, made important contributions to the public use of history. Most prominent among these was his work as an expert witness in the celebrated lawsuit stemming from Deborah Lipstadt’s designation of the historian David Irving (correctly) as a Holocaust denier. Evans’ systematic, evidence-based dismantling of Irving’s web of lies and distortions, as illustrated in the trial transcript and in his subsequent book about the experience (Lying About Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial), is a model for the aspiring historian, as is the clear and unassuming prose in which it is couched. It is well that historical scholarship has so apt a practitioner and defender, for the questions surrounding National Socialism and the Holocaust are some of the most profound facing the modern world, and the threats posed by liars and cynics, but also by enthusiasts are legion. The manner in which Evans has taken up the cudgels against them is, in the most literal sense, exemplary.

The Third Reich in History and Memory brings together 28 occasional pieces written by Evans over the course of the last fifteen years, mostly book reviews, some of which have been aggregated (when they address a common topic). Oddly enough, it is the predominance of book reviews that makes this is an excellent book for non-specialists, as well as for those well-versed in the history and historiography of National Socialism and the Holocaust. Evans’ familiarity with these vast literatures is encyclopedic and he easily could, but does not, fall into the common error of the scholarly virtuoso of assuming a similarly expansive knowledge in one’s readers (or not caring about it).

Evans writes in a clear and unaffected style. More importantly, he is careful in each instance to let the reader know what it is at stake in the matter under discussion, rather than simply assuming his readers know this, or relying on the gravitas of the topic itself to make a suitable impression. Thus, in his review of Heike Görtemacher’s 2011 biography of Eva Braun, Eva Braun: Life with Hitler, Evans lets us know why it is, outside of the kind of morbid curiosity for which less scholarly treatments of Braun’s life have been fodder. A discussion of Braun’s life and her relationship with Hitler not only answers questions about her, but also illuminates the dealings and tensions that went on within the circles closest to Hitler himself. Framed in this way, Evans’ assessment of Görtemacher’s book carries far greater weight than it might have if the interests of the reader had not been properly engaged at the outset.

The collection is broken down by subject areas, running roughly chronologically from the prehistory of the Holocaust in late 19th and early 20th century German colonialism all the way through the postwar issues such as reconstruction of the memory of the Holocaust. But the meat of the book is in its central sections which address, often in overlapping fashion, issues such as the degree of popular support for Hitler, the levels of coercion applied to German society to achieve it, the economics of the Nazi state, and the relationship of the Nazi Party to the preexisting structures of the state.

The question of consent versus coercion is of particular importance for Evans. This is hardly surprising given how large it has loomed in discussions of the origins of the Holocaust in the last two decades, and in particular in the wake of the publication of Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s deeply flawed Hitler’s Willing Executioners. That book is not directly addressed, although readers of Evans’ writings on the topic (such as his analysis of the origins of National Socialism in The Coming of the Third Reich) will already be clear how little he rates Goldhagen’s approach.

Evans is more interested in responding to claims from both ends of the political spectrum that popular support for Hitler was widespread and generally voluntary. One commonly cited basis for this claim is that, by the mid-1930s, the concentration camps contained only 4000 or so inmates, down from tens of thousands in the early days of the regime. As Evans notes at several points, this has little to do with the broadening of popular voluntary support for Hitler, and much to do with the fact that by that point, the apparatus of terror had been shifted to the state judiciary.

Support for Hitler, and for the Nazis generally (which was not always the same thing) had varied sources ranging from ideological commitment or fascination with the person of Hitler at one end of the spectrum, to simple advantage-seeking at the other. Acquiescence, which comprises a much larger segment of the population, was generally a matter of self-interest, whether in terms of professional advancement, or profiting from “Aryanization” of Jewish property, or the fear (by no means unjustified) of being tortured or killed for manifesting dissent.

One apposite example of this is Evans’s review of Götz Aly’s Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State. Without the background provided by Evans, it might not be obvious to the casual reader either that Aly was a historian of pronounced leftist sympathies, or that he was among the most extreme of the functionalist interpreters of the Holocaust (i.e. those who see it more as a result of dynamics within and around the regime rather than as a direct expression of the intentions either of Hitler or his immediate cohort). This is important, because it illuminates what is at stake when Aly claims that the German population (at least those who fit the restrictions of the Nazi Volksgemeinschaft) were convinced to support the regime with commodities stolen from its victims.

This approach, which is part of a large tendency to view National Socialism as one form that modern capitalist societies can take on (albeit a very extreme one), is an expression of Aly’s leftist politics. And in terms of general approach, he is not wrong. But, as Evans points out, and as any careful reader of Adam Tooze’s Wages of Destruction will know, in this case quite the opposite is true. As Evans reminds us, Tooze showed in extensive detail the ways in which the commodity producing sectors of the Nazi economy were starved for resources by demands of rearmament. While Evans gives Aly credit for his commitment to primary source research, he nonetheless (and quite correctly) notes that Aly’s evidence doesn’t make the cut in terms of an adequate defense of his thesis.

Evans is judicious but also unsparing in his criticisms. His review of the edited collection Das Amt und die Vergangenheit illustrates both these traits. Das Amt caused a huge stir in Germany when it was published in 2010. It was meant as a debunking of the myth, still commonly circulated around the turn of the century, that senior bureaucrats in the Foreign Office had resisted the influence of Nazi interlopers and were, thus, not to be viewed as complicit in their misdeeds. In one sense, Evans notes, the project was successful, adducing a mass of primary source evidence to show that the old hands viewed the Nazis quite sympathetically and that none but a few marginal figures engaged in anything that could seriously be termed resistance.

But Das Amt had serious flaws as well. Originally put in the hands of senior professors, it had (due to age and professional commitments) eventually been farmed out to younger scholars, several of whom were not yet in possession of their doctorates. This accounted, Evans claims, for the two main deficiencies of the project. The lack of experience and scholarly breadth lead to a narrow focus on complicity of old Foreign Office hands in the Holocaust, to the exclusion of questions of their complicity in other matters (such as the launching of a brutal imperialist war). The role of junior scholars also explains, so Evans notes, a general and very damaging lack of familiarity with the secondary literature on the topics under discussion. These problems were quite serious because although overall argument of the book was correct, the deficiencies in focus and scholarship provided footholds for injudicious criticism.

This, in a nutshell, is Evans’s approach. Responsible scholarship is a matter of both adducing relevant evidence, but also of familiarity with the current state of the art. This is of particular importance in the case of historical analysis of the Third Reich and the Holocaust. Their entanglement with current political crises in Europe, as well as with the still extant streams of anti-Semitism in Western society (and elsewhere) lays a heavy burden upon those engaged in this area of scholarship. Evans has done both students and general readers a great service by holding his colleagues to account, for it is incumbent upon those who know to keep standards high.

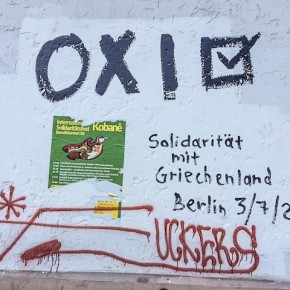

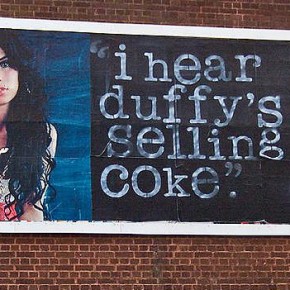

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.