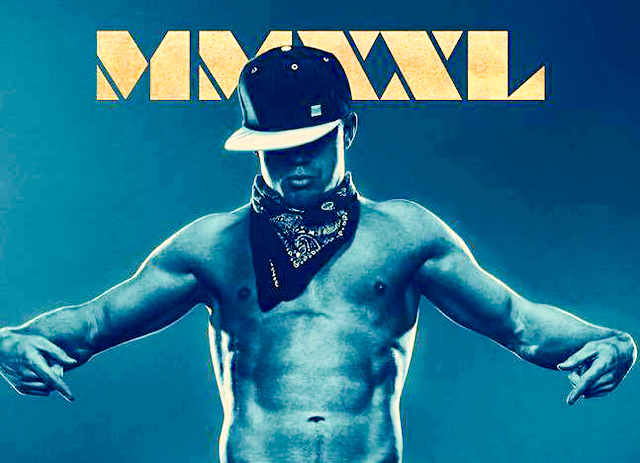

“You’re Welcome,” reads this most appropriate tagline to the sequel to Magic Mike. Once a snide reminder of forgotten thanks, this phrase has come to mean the inevitable grateful outpouring in response to something highly desirable or cool. The anticipated gratitude could be for a number of things.

First, and foremost, there is the presumed appreciation of so many lovely bodies on display, performing the beauty standards of a cut yet gentle masculinity. Adding to that, this sequel delivers bodies in a context significantly more celebratory than its predecessor.

A sweet comedy with hints of drama, Magic Mike XXL comes with little of the prudishness and judgement that can so often inflect the work of the original’s director, Steven Soderbergh.

The warmth extends into expressions of inclusivity. This is a story of male friendships that never once delves into the nasty and all too typical territory of the gay panic joke. When Mike (Channing Tatum) and Tito (Adam Rodriguez) find themselves in a hotel room with one bed to share, this never even enters the conversation. Rather, they carry on the prior discussion and flop down. It is a comfortable and confident intimacy that should be model for men everywhere. The sequence at the drag club is (barring one character’s incongruently campy Carmen Miranda get-up) is similarly impressive. When they vogue, they are preceded by real-life celebrity voguers, MC Dashaun Wesley and Javier Madrid, and their own dancing is respectful, not mocking of this vibrant yet often misrepresented community.

More queer-friendly than the usual mainstream fare, the film also aims to represent far more people of colour than their initial—not to mentioned questionable— count of two (one Latino, one Armenian). This comes with Jada Pinkett Smith as Rome, and her club, which cater to an African American clientele and feature black strippers. Sadly, exceptionally poor lighting compromises this welcome diversity. (Indeed, it’s both shocking and all-too-typical that even the most skilled Director of Photography (Steven Soderbergh in his usual alias of Peter Andrews) has not figured out how to film for Black skin.)

Meanwhile, Rome’s “queens”, the female clientele, embody what is also so appealing about the film: Representations of women of all sizes, shapes, and ages delighting in sexual desire, with none of them punished for it. A sequence with Andie MacDowell, in which older women raucously engage with the strippers—or “Male Entertainers,” as Big Dick Richie (Joe Manganiello) would have it— could have pulled out any number of “cougar” jokes, an ugly trend intended to shame women for desire and to suggest them less than human for their desire or power. But it didn’t. These factors among others have led many to praise Magic Mike XXL for its feminist values, among others.

So far, so filled with a puppy-ish charm that aims to make good on its anticipatory “You’re Welcome.” However, there is another inflection in the presumed gratitude that is less than welcome, the one than suggests the desires they project onto their audience are, in fact, the audience’s as opposed to their own. Perhaps now, I reveal my own prudishness, but I often wonder how many women enjoy being grabbed by a dancer and having her face pressed into his crotch. It’s not to say one wouldn’t get there on her own, but this insistence is a little too familiar in the world of regular encounters where the goal is to direct attention to male desire. In another dance, two women get down on their hands and knees to act as brace for Mike during a particularly energetic show of skills. Is it actually a female fantasy to act as support for male displays of prowess? Or is this again an all too familiar reiteration of the everyday, imagined as what a woman wants? To be fair, Donald Glover’s crooner (additional thanks for casting him) mixes this up a bit in his personalised serenades, but so much of this film seems to be about male desire projected as female desire that the “you’re welcome” becomes a response to their own gratification.

Indeed, what can we make of Big Dick Richie’s own journey and quest for a woman who can accommodate his manhood (and cause for his nickname)? Lamenting his loneliness, he eventually and predictably finds his match (Andie MacDowell’s older woman). To the film’s credit, she is not mocked for this. The sex positivity is welcome. But when this match is called his “glass slipper,” a reference to Cinderella and the fairy tale romance, curious meanings are smuggled in.

On the surface, it gestures to the romantic fit, the discovery of the one, and something men may want as well. There is a sweet wistful quality to it, until one realises that she has been likened not to the prince, but to an object that helps Richie achieve his dream: the full penetration he has sought but so many women refuse. This adaptation of the fairy tale, and ostensibly a woman’s fantasy, calls attention the degree to which this film (and perhaps other materials presumably for women) advance the cause of male need and desire.

The final sequence at the stripper convention is the epitome of this projected desire. Dispensing with the firemen and other standards of the male stripper, the men explore dance routines based on what they like, and what they want. In part this is an appealing reclamation of power in a story of men agonising over fear of failure; they will perform their dreams for the audience: Tito plays a candy man; Richie, a groom; and Mike, in a performance of mirrored dancing with stripper Malik (Stephen Boss) leaves one wondering if his main wish is to be black.

Combining crotch grinding with these aspirational performances seems to confirm the centrality of the men’s desire, even as the women seem to love it. It’s not that women can’t love this kind of physicality, but that the choreography somehow makes them objects and subjects: If one has the misfortune of getting called up from the audience onto the stage, she will become a prop more than the lucky recipient of tactile close-up. Such is the fate of Richie’s “bride”, who is strapped into a sex swing, only to be left dangling, her legs still locked into the stirrups, for the remainder of the film.

To observe this projection of male desire onto a female audience is not to dismiss or disparage the film. Magic Mike XXL is good-natured and fun. And it opens interesting questions into the production of a “female gaze,” a reversal of film scholar Laura Mulvey’s generative notion of the “male gaze.” This idea suggests that women in film are structured as the object, the “bearer of the look,” whereas men are the active viewers whose pleasure was paramount. A female gaze suggests the possibility of the reversal, but as Magic Mike XXL shows, even in the most amiable efforts, this endeavour is not quite so simple, inevitably reconnecting to male desire as one of the principal drivers.

Of course, given that this is a buddy comedy and road picture, perhaps it would be worth reminding audiences that this film is clearly for (straight) men as well. You’re welcome.