“Naturally, the peasants want Haiti for the Haitians,” concluded the Senate Select Committee on Haiti of the 67th United States Congress in 1922. And naturally, that was not going to happen until they were ready, in the judgment of the US government.

“Ready” ostensibly came twelve years later, in 1934, ending an occupation that began in 1915, following the murder of pro-American Haitian President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam on July 28th, 1915.

The day before, he had estimated that the mass execution of 167 political prisoners, including his predecessor, who had criticized his depending reliance on the US, would cow a restive populace. Instead, it drove them to revolt. The first Marines landed within hours of his demise as the government, Haiti’s sixth in four years, fell to pieces.

It was not the first or the last such intervention ordered by President Woodrow Wilson in Latin America, having been preceded by an abortive action in Mexico the year before, and by a more successful action in the Dominican Republic a year later. As Wilson had stated in 1889, when he was still only a professor at Wesleyan College, the world was entering a phase of history in which “certain influences are astir … which make for democracy the world over.” He was, though, quick to distinguish between the “anarchism” of unregulated liberty, and the proper character of liberty: the American kind. Given Wilson’s record in Latin America, it is apparent that he saw the former prevailing in the newly emerging democracies of the period, and decided that the latter required direct military interventions to come off.

A wide range of interpretations surround Woodrow Wilson’s decisions to occupy Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Images of Wilson the scholar, Wilson the progressive, Wilson the internationalist, and Wilson the disciplinarian are all used to explain the head of state. Wilsonian interventions in the Caribbean littoral should be largely understood in light of Wilson’s idea of American identity, which through all of the geopolitical and financial considerations he faced, was the overriding framework for policies he thought were consistent with his evolving vision of Washington’s place in the world.

Today, Wilsonianism would be termed “liberal internationalism,” for though it was justified in professed concerns over property rights and countering hostile foreign influence in the region (Germany’s, in the case of Haiti), for more hard-nosed consumption, there was always a more ideological, paternalist design at work. While it was not inaccurate for General Smedley Butler to later depict his service in Haiti as an act of making it “a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in” in light of how the US took over the country’s finances (National City Bank, or Citibank as it is known today, controlled Haiti’s treasury bank from 1910 on) – this was hardly the animating force behind the President’s decision.

To understand the genesis of his approach to Latin America, Wilson’s initial approach to the Mexican Civil War must be understood. The President viewed European influence in Mexico as an affront to the country’s national sovereignty – even though the US itself wielded similar influence in Cuba and Panama at the time. Such influence was seen as proof positive that America had to act to “[fix] in the minds of the people in Central and South American their [positive] estimate of us” in order to generate positive feelings to further American penetration of these countries. That Wilson’s policies in Mexico were stymied time and again did not lead him to forgo military intervention in the Dominican Republic and Haiti. If anything, these setbacks encouraged him to “to take the bull by the horns and restore order in Haiti” whereby the ends justified the means.

In 1913, at an economic conference attended by ministers from several Latin American nations, Wilson proudly announced that soon they would all experience “emancipation from the subordination” of foreign economic concessions. But in proclaiming sympathy with these nations to shake off the “hand of material interests,” Wilson used the language of Progressivism to justify American’s implicit dominance in the process of guiding these countries through the wilds of unfettered liberty, an anarchy of social revolution. The “lasting and stable peace” Wilson spoke of at this time was, he asserted, contingent on the proper behavior of governments, an assertion of character responsibility by Latin Americans derived from his own writings on US history.

Wilson spoke of America’s character in terms of Manifest Destiny, a claim that in Wilson’s era was justified, by no less than Wilson himself for that matter. Wilson viewed American exceptionalism and expansionism as one in the same: America’s character – the character he asserted made it uniquely fit for popular institutions – would now be manifested through expansion of ideological boundaries and American commerce. This paternalism was fully evident in the Caribbean. For instance, the US used the Gendarmerie to force the American-written constitution onto the country in 1918, a document that suspended real Haitian democracy. Even this was not enough for the occupiers. Legislators in the rubber stamp parliament set up thereafter were not even trusted to pass legislation on their own, without “consultation” of the American legation.

Force was never in short supply to enforce these terms on the country. Over 15,000 people died during the course of the occupation, at the hands of the Marines and their fellow Haitians, both the rebels and the US-trained national police (which was held in fearful, yet low, esteem for its ineptitude and brutality). Even some American officials in the country felt that the 1918 Constitution was forced onto the Haitians at gunpoint, though they not only acquiesced to intimidation tactics but also actively encouraged the US-officered Gendarmerie to arrest anyone who spoke out against the 1918 Constitution during the referendum.

The primary accomplishments of this document, which was drafted by then-Secretary of the Navy and future President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, were to open Haiti to (American) direct investment and property ownership. While the constitution imposed by the US ignored and invalidated Haiti’s own democratic institutions, Wilson did not see it for what it was. As he had asked in 1885, the year Wilson published his first book on American politics, “Why has democracy been a cordial and a tonic [to the US] … while it has been as yet only a quick intoxicant or a slow poison to France and Spain, a mere maddening draught to the South American states?”

For Wilson, economic and structural reasons as to why democracy took hold in different ways in different countries mattered less than racial determinism. Similar actions taken in the Dominican Republic, including the imposition of full financial control over the country, suspension of elections, and development of a constabulary to serve as an administrative force in the country, was a manifestation of the principle that “we must govern as those who learn; and they must obey as those who are in tutelage.” Wilson, and a great many of his “learned” contemporaries, quite obviously viewed non-white adults as possessing the mental acuity of children.

This heavy-handed approach was founded in Wilson’s own experiences as a white, post-bellum Southerner. While ostensibly supportive of land reform in Mexico and the Caribbean islands, Wilson did not believe that post-Reconstruction agrarian reform in the American South had done much good. Wilson described freed slaves as “insolent and aggressive . . . a host of dusky children untimely put out of school,” again, language and imagery that would be repeated in scholarly tomes and the yellow press with abandon as the US stretched its legs into the Caribbean, but also into China, the Philippines, and by 1918, the fringes of the defunct Austrian and Russian Empires. The educator metaphor was applied to Wilson not just at home, but overseas, where Wilson compared the US governors of the Insular Territories to schoolteachers in 1901.

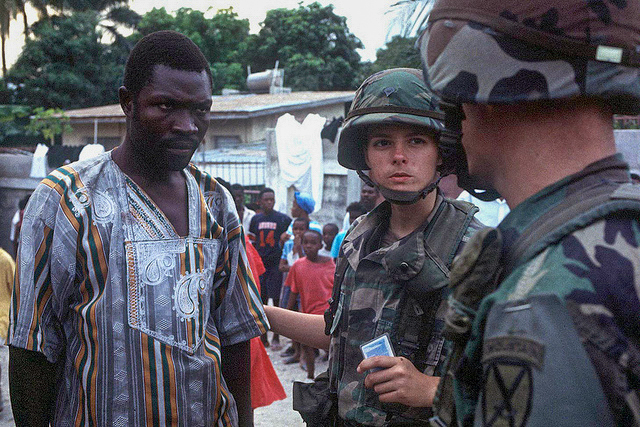

The Marines likewise spoke of Haitians and Dominicans as wayward children to varying degrees, bringing with them not just the language of paternalism, but the forceful and clearly unequal provisions of segregation back home. The occupiers often deferred to the country’s mulatto elites, for example, regarding the bulk of the population outside this privileged class as “the peasant class,” not far removed from darker jungles. As editorialists noted, by 1930, Haiti had even less of a semblance of self-governance than the Philippines did. The American financial advisor to the national treasury held powers like that of a dictator, Haitian politicians complained.

Even General Butler was not immune to such sentiments. His remarks in 1921 that the Marines were “trustees of a huge estate that belonged to minors” and the Haitians their wards were par for the course, as was The New Republic’s earlier declaration in 1915 that the US should secure “the good behavior of the petty governments in and near the Caribbean Sea” by appointing top men to go over there and run things properly. Men of merit greater than the sort of dullard usually appointed as part of a patronage system back home in the US. Such a view, coming out of this new mouthpiece of the progressive movement, was absolutely Wilsonian.

A Colliers magazine article from 1928, “King Leatherneck,” is even more telling than these more subdued expressions. The Gendarmerie dispatched one Lieutenant Faustin E. Wirkus, lately of Pennsylvania, to Gonâve Island, where he becomes king, Le Roi, inaugurated by the locals in a religious ceremony related to the reader in lurid detail. Although it was “not within their democratic scheme of things” for the occupation authorities to let this pass, King Wirkus I is praised by the magazine for being “a miracle of ‘happy efficiency,’ in a post where many a white man would have gone crazy.”

The way this story is told is more telling of popular attitudes towards Haiti, since despite the tone of the account, Le Roi himself comes through as someone in a hardship posting resignedly accepting some indigenous trappings to make his job easier. He is pictured seated alongside his “Queen,” an elderly matron named Ti Meminne whose elevated position in the community was sought through this public ceremony. Modern counterinsurgency doctrine might find this accommodation laudable, especially since Le Roi disliked the notion of fraternization – Wirkus said he preferred “pretty American girls, preferably chaperoned by their mammas” to a “native harem.”

Photographs courtesy of Expert Infantry. Published under a Creative Commons license.