The first five years of the occupation were as dangerous and brutal as anything out of South Vietnam during the 1960s, or Iraq in our own time. Even as peace settled in, an account of the 1917 parliamentary elections reproduced in a Haitian newspaper for the centennial is instructive of the problems faced by the Yanqui occupiers.

In one incident, the Marines reportedly threatened a campaign official with waterboarding and carried out a night raid on the house of a candidate suspected of buying votes ahead of the national contest.

Unfortunately for Haitian democracy and the Marines’ credibility, it seems those they targeted were actually the victims of a smear campaign by their political rivals, who took over the local district offices thereafter.

Further into the interior during this period, practices similar to those first implemented in the Philippines (and the Indian Wars a generation prior) prevailed in Haiti, with villagers herded into camps to separate them from the guerrillas or of summary executions for real and imagined crimes. Even the end of the fighting did not necessarily lower tensions. In 1929, the incoming Roosevelt Administration faced a potential crisis in Haiti just as it took office, as a result of the massacre of demonstrators by Marines inDecember, following the imposition of martial law. Little remembered now, the fallout probably helped spur FDR’s decision to draw down the US military presence by 1934, ahead of the original date of 1936 anticipated by the outgoing Hoover Administration. Haiti’s economy, though, remained under effective US control for far longer.

Not all administrators of the occupation were boorish bigots or war junkies, of course. Nor, despite the death toll or other indignities inflicted, was it impossible to find collaborators from either well-to-do ancien regime or the poorest faring communities. Many recruits, especially in the Gendarmerie, were motivated by the chance to escape grinding rural poverty, eventually becoming a new elite class themselves. Others sincerely hoped the US could help the country escape the vicious cycle of coups and perennial indebtedness that had characterized the recent past.

Nothing bespoke of this aspiration better than the building of the country’s presidential palace. It was completed in 1920, though later destroyed by the massive 2010 earthquake that brought in a UN “humanitarian occupation” almost as large as the American one a century prior. The great white edifice was designed by a future Haitian senator who took some obvious inspiration from the American White House and Capitol Building, and some assistance from a detachment of Marine Corps engineers stationed in Port au Prince.

Perhaps nothing spoke better of the reality of these aspirations than how the American bureaucrats charged with revising the national education system settled on a vocational training focus, which was resented by the population in part because the teachers brought over to educate a mostly rural populace were Southern agronomists who had no experience with growing in the Haitian climate. This poor planning is ironic in light of how the aforementioned Select Senate Committee report clucks over the fact that impoverished Haitian farmers were ignorant of many common farm tools available in the US.

One wonders where in the middle of Haitian poverty and American arrogance, which side was least likely to recognize what they needed to do to fix them. With this level of ignorance in mind, it is not hard to understand why an astonished Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan exclaimed “Niggers speaking French!” when he was first told that Haiti was a Francophone nation. This elder Democratic statesman was probably floored by the thought of poor black farmers speaking the language of the Enlightenment.

The US, did, at least, build new infrastructure in the country in the course of 19 years of occupation. Yet much of it was built using corveé labor organized by the security forces towards security-related ends (roads for moving troops too priority, other uses for them being incidental), or by foreign capital that retained ownership of the properties, especially railroads. The undemocratic manner of these efforts was visible, but not anathema to Wilson’s progressive worldview: it embodied a belief that the Caribbean peoples were simply not yet ready for self-determination but that the betterment of their character could begin with material improvements, albeit with no say in the matter.

Regarding the corveé in Haiti and the Cacos Revolt that resulted from such practices, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels equated the suppression of the Cacos with teaching them a lesson, like unruly children. One particularly gruesome lesson involved the public display of the body of rebel leader Charlemagne Péralte after he was betrayed and killed in an ambush in 1919. His successor perished a year later following an abortive assault on the capital, popularly remembered as “The Debacle,” marking the end of organized resistance to the Marines’ presence.

When Wilson claimed that he would “teach the South American republics to elect good men,” he felt his “strong hand that will brook no resistance” in the full application of American political tutelage that would lead to the development of a proper national character among those not fortunate enough to be born WASPs. That such men would also, as officers of the US armed forces, allow for a corpse to be paraded around in a manner not unlike the ghoulish display that President Sam’s remains were subjected to in 1915 by the mob, seems to have been lost on many observers. Wilson’s own reaction to this incident is unknown. A month before it took place, he had been partially paralyzed by a stroke and confined to bed, his presidency effectively finished.

The US government’s policies towards social changes in Haiti and the Dominican Republic bore both an imperialist character and a Progressive character, both of which were also apparent in the Dominican Republic, where the occupation bills were paid partly by the country’s forfeited customs revenue. Obviously, protection of financial and landed interests – including those of that multinational or multinationals, United Fruit – were important to the White House: they were important even in Mexico at the earliest, inchoate stages of intervention at Veracruz in 1914. But Wilson was not just looking to do Wall Street’s work. He was hoping to assert his emerging vision of a tutelary role for the US in former European colonial possessions.

That the Americans sent over carried themselves much like the former administrators, as The New Republic’s Katharine Sergeant Angell reported in 1922 in an article on the divide between “Haitian” and “Occupation” society did help. “Where else,” she wrote after a three-day visit among Port au Prince’s Francophone high society, “can one live in a villa with nine servants, horses, automobiles, on a diet of chicken, alligator pears, and heart of palm for a few cents a day, fine French wines and native rum for the ordering, and all on a second lieutenant’s pay?”

Generations of American administrators yet to come in French Indochina would surely have recognized something in this account, as well as the hostility that the “Occupation” showed to her and other do-gooders coming over to investigate allegations of abuse and misconduct.

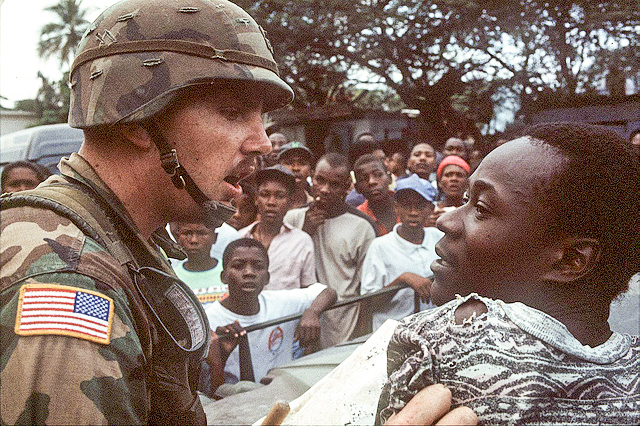

Photographs courtesy of Expert Infantry. Published under a Creative Commons license.