I spend a lot of my time thinking about and writing about Jews. Much of my work takes place within the confines of the Jewish community, but I also try and engage the wider world with Jewish issues. That often leads me to publishing think pieces and reviews in a range of ‘non-Jewish’ publications such as the The Guardian, The Independent and more.

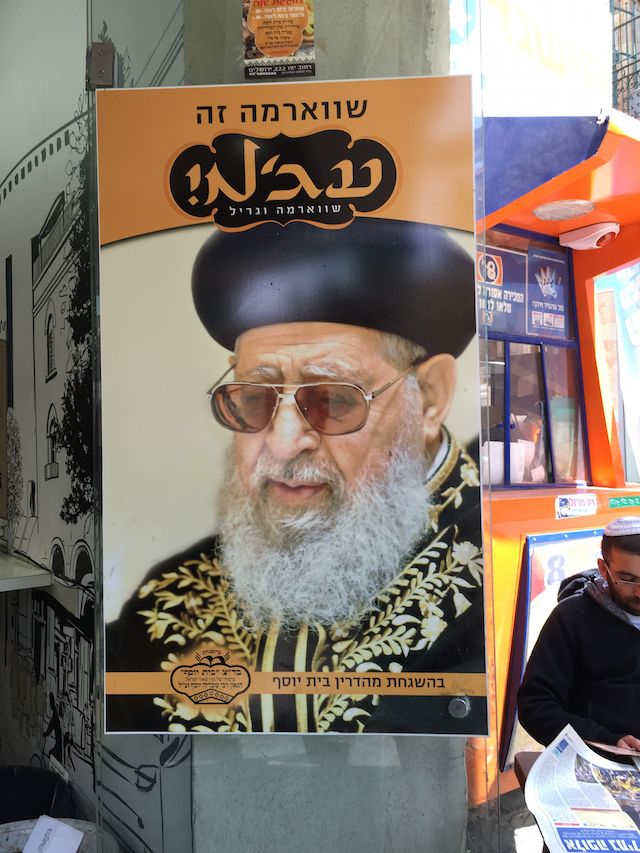

I’ve been doing this for a while now and I don’t exactly know when I started to notice something odd about my articles: some of them were illustrated with photographs of strictly orthodox (Haredi) Jews. I have rarely if ever discussed Haredi Judaism in my writing and, in some cases, the argument I was making excluded them completely.

Take this piece for example. Published at the height of Operation Protective Edge, in 2014, it argued that the UK Jewish community has a complex relationship with the conflict and the pro-Israel consensus that used to hold sway was in the process of fragmenting. But the Haredi community’s relationship with Israel is completely different to the rest of Britain’s Jewish population, and my article did not deal with this at all. Perhaps I needed to make this clear.

Even when the subject of the article would seem to fit a photo of Haredim a bit better – as in this piece on the possibility of a violent attack on UK Jews – the illustration is misleading about the nature of UK Jewry. After all, the UK Haredi population is, despite a rapid growth rate of about 4% per annum and a population of somewhere between 30-60,000, is still a minority within the 300,000 strong UK Jewish population. They live lives that are largely separate from the rest of the Jewish community and respond to Jewish concerns in a very different way.

My own experience has led me to notice just how many articles about Jews are illustrated with pictures of Haredim. When, at the end of July, some new figures about anti-Semitism in the UK were published, The Independent, the Evening Standard, the Mirror, the BBC and the Daily Mail all illustrated stories with pictures of Haredim. So I’ve started a Tumblr blog to post as many examples of the phenomena as I can find. What most of these articles have in common is that they do not discuss Haredim directly and, at times, the illustration is wildly inappropriate.

Take this piece on Russia Today which reported on a letter by British Friends of Rabbis For Human Rights to the outgoing Israeli ambassador, protesting the proposed demolition of the Palestinian village of Susya. It was illustrated by a picture of Haredi Jews from the anti-Zionist Naturei Karta sect on a pro-Palestinian march. Rabbis For Human Rights, while critical of Israel, is made up largely of progressive and some modern orthodox rabbis, most of whom are Zionist to some degree – they have little in common with Naturei Karta.

Certain features occur repeatedly in these photos: they are usually photos taken on the street (often from behind), they are almost always pictures of Haredi men with beards, they contain very few clues as to the context in which they were taken. In fact, the same pictures tend to get reused repeatedly. This one, by Oli Scarff, has been used to illustrate dozens of articles, some about the Haredim, some not:

There’s no mystery as to why pictures like these are used so often. In today’s media environment, in which a constant clamour for more ‘content’ goes along with repeated downsizing and multi-tasking of editorial staff, sub-editors and photo editors are under enormous pressure to get articles finished and up on the web as soon as possible. Combine that pressure with a need to make content instantly eye-catching and ‘clickable’, together with a frequent ignorance about who Jews are, and its understandable why editorial staff will reach for the most obvious and striking image that they can find.

But even if I can empathise with the harassed workers at today’s unforgiving journalism coalface, their picture choices have implications that are worth thinking through.

For non-Haredi Jews like me – still the majority in most countries with a Jewish presence, albeit a fast-growing one – it is sobering to think how far the image of the generic Jew remains, for many people, the bearded and black-hatted Haredi Jew. Despite over 200 years of emancipation, the highly visible presence of Jews of all stripes in public life and the ever-flowing stream of writing for, about and by Jews – it seems that the Haredi Jew is the ‘real’ Jew. As someone who has spent a large chunk of his career explaining Jewish life in all its diversity to non-Jews (including writing a book on the subject), I can’t decide whether people like me are simply failing, or whether the image of the Haredi Jew is so powerful that whatever we do, we will never entirely be able to counteract it.

I want to be clear about something though: I do not feel embarrassed or humiliated to be associated with Haredi Jews. Although there are many features of strictly orthodox Judaism that I find highly problematic, I recognize that I am connected to them: we share a history, some religious rituals at least and the experience of antisemitism. The Haredim are not my shameful, Neanderthal cousins who I must repudiate in order to convince the world of my civilized, emancipated Jewishness.

Yet it’s still important to ensure that the world understands the differences between different kinds of Jews. Different kinds of Jews have different interests, and values. Haredi Jews in the UK, for example, are highly concerned about proposals to curtail benefits for families with more than two children – an issue that barely resonates with non-leftist, non-orthodox Jews. Conversely, progressive Jewish support for gay marriage is, to say the least, not shared by the strictly orthodox. In a multicultural society, one cannot respond to the needs of ‘the Jews’ as a unity. When all Jews – or any other group – are homogenized, the lived reality of Jews as a diverse collective is effaced.

Haredi Jews themselves also need to engage with the implications of being the ‘public face’ of Jewry. While they may well like the idea that their ‘authenticity’ is being tacitly upheld, there are some disturbing features of the tendency to use photos of them to illustrate articles on Jews. Although they are unlikely to have read Edward Said, Haredim may well feel exoticised and othered as a mysterious black-hatted sect. Many of the photos used in the media seem to suggest furtiveness, given that so many of them are taken from behind. There is certainly no appreciation for the breadth of Haredi life.

Such photos also reveal an irony at the heart of Haredi culture. One of the reasons why Haredim dress the way they do is because of a concern for tznius (modesty), which applies both to men and women. By wearing similar clothes that hide much of the body, Haredim try to counteract pride, vanity and individualism. This may work to an extent in large Haredi communities that are insulated from interaction with non-Haredim, but in multicultural societies, the requirements of tznius can actually lead to the opposite: by marking themselves off as different, the Haredim are gazed at, marked out and exoticised. They are visible in their invisibility.

Perhaps the converse of that irony is that non-Haredi Jews such as myself, become invisible when they wish to be visible. In writing for comment pages – like so many other publicity seeking Jews of my kind do – part of me desires that the non-Jewish world pays me attention. Yet because Jews like me do not look different enough, editors need to resort to the exotic figure of the black-hatted Haredi Jew.

Maybe though there is something peculiarly Jewish to this whole issue: we aren’t happy when we’re visible, when we’re invisible, or any other time. It’s no wonder that time-pressed journalists have to reach for predictable pictures in the face of this irresolvable ambiguity.

Photographs courtesy of Oli Scarff and Joel Schalit. All rights reserved.