Since March, Islamic State has been implementing a string of attacks in Northwestern Yemen, most recently with a car bomb attack on June 29 that killed dozens of people. Its gradual rise in the country, and competition with Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), is best understood through a discussion of failed counterinsurgency policies by Saudi Arabia and the United States.

Islamic State is a consequence of the War on Terror, and this is true in every country where it currently operates. It arose rapidly in Western Iraq, and Northeastern Syria, mainly because it had access to combat veterans, fundamentalist propaganda, logistical networks, supply lines, and sources of funding that were previously used during the Iraqi civil war. That militant nexus roared back to life in opposition to Assad, and after some time, was increasingly consolidated by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s forces in Islamic State.

The organization has developed considerably since then, owing to various resources it has either seized or obtained through rentier enterprises. These material advantages have combined with international attention to lead to Islamic State’s increased hegemony in religious militant discourse. Last November, Baghdadi leveraged these gains by announcing efforts in several countries including Yemen, in spite of criticism from AQAP. It has been steadily growing since then, and particularly after March 20th, when it executed quadruple suicide bomb attacks on two Zaydi Shi’i mosques in Sana’a.

So far, there are two reasons that Islamic State has been successful in Yemen. The first is that it is benefiting from the political and ideological vacuum that has been widened by the failure of internationally-mediated democratization efforts, which have now collapsed into direct military intervention. The second is more specifically that the Obama Administration’s efforts at counterinsurgency have actually empowered Islamic State at the expense of AQAP.

Islamic State is one of several armed factions that have gained strength in Yemen in the wake of the failure of the National Dialogue Conference. After two years of protest and unrest, the NDC was assembled in March 2013. It was supported by the United States and the Gulf monarchies, with the objective of bringing together various factions to design a new constitution and political framework.

NDC critics were immediately alarmed at its lack of democratic legitimacy. It appeared that the Yemeni political elite, represented by President Hadi, had made independent decisions about which representatives would dialogue about the country’s future. This was occasionally acceptable, as proven by the diverse presence of the Houthis and Al-Hirak, however the non-representation of revolutionary youth made it clear that the NDC was a reactionary measure.

By its conclusion in January 2014, additional concerns emerged over federalization proposals that divided Houthi areas of northern Yemen into two districts. It seemed that the NDC was attempting to marginalize Houthi power and influence in the country. Spurred on by insecurities about its future, and the sluggish pace of reforms in Sana’a, the Houthis took advantage of the city being relatively unguarded and seized the capital in September 2014.

It is obviously no coincidence that as a result of the unrest, Islamic State began moving into the country, with Baghdadi’s announcement occurring two months later. It also posted its first major attacks shortly before the Saudi-led coalition formally intervened on March 26.

There are currently two problems in Yemeni politics that are facilitating the expansion of Islamic State. One is that the government has either been too busy quelling revolutionary upheaval to pay attention to jihadist activity, or willingly ignoring it in order to force support from the United States. Another is that Arab Spring protests failed to lead to a lasting democratic framework in Yemen, with already imperfect NDC proposals either being ignored or crudely implemented.

These realities opened the terrain of revolutionary possibility to various other groups, not all of which offer a progressive vision of the future. Islamic State is one of these factions, which has been gaining influence through authoritarian measures made possible by the deficiencies of the post-revolutionary national consensus.

However, it is important not to overstate domestic factors behind the rise of Islamic State. The group’s current ascent is also a consequence of the White House’s anti-terrorist activities. Generally, the Obama Administration has violently destabilized Yemeni society, which has made it extremely difficult for a new democratic consensus to consolidate itself in the country. This has occurred through a complex process that requires an extensive critique of American intervention to fully understand.

The White House’s continued support for local anti-democratic allies like Hadi, and Ali Abdullah Saleh before him, have significantly worsened the problem, along with its reactionary allies in the Gulf monarchies. Obama has also been unable to contain the regional consequences of past warfare, which include rampant sectarianism, and the very existence of groups like Islamic State. Additionally, the United States continues to support market-driven developmental policies in countries like Yemen, leading to extreme violence and social unrest, particularly in rural and tribal areas.

This is in addition to more specific problems in the White House’s approach to AQAP. The Obama Administration’s aggressive efforts to curb the organization have had severe consequences in empowering its rivals in Islamic State. This is frequently overlooked in standard critiques of the War on Terror, which focus mainly on collateral damage such as civilian death tolls, social unrest, and mass internal displacement. These criticisms are important, since they help explain why Yemeni society has become so fragmented that Islamic State is able to expand itself.

However, Obama’s critics repeatedly ignore the core strategic problem, which is that the White House’s focus on executing AQAP leadership has allowed Islamic State to cannibalize it for money, talent, and influence. The United States has been so obsessed with bombing jihadi commanders that it pays little attention to the troops, resources, and supporters they leave behind.

As a result, when a new group like Islamic State comes along, it simply absorbs the weakened group’s disoriented remains, and presents a new security threat that requires further intervention. This is essentially what happened in the fallout of the Iraq troop surge coordinated by General David Petraeus in 2007, which disrupted the insurgency and lowered civilian death tolls, but left the previously described militant nexus in place.

The United States has now created a situation where it will need to engage in far greater efforts of counterinsurgency if it ever wishes to control the problem. Of course, it currently lacks the strategic capacity, and political will, to do that. The White House is also still enamoured with the Pentagon’s continued insistence that playing jihadi whack-a-mole through drone strikes is an intelligent long-term strategy, rather than a deeply flawed tactic with numerous legal and humanitarian consequences. Observers should realistically expect that domestic and international actors will see a surge of brutal religious militancy as a result of their activities in Yemen, with unknown consequences.

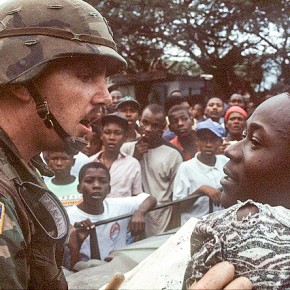

Photograph courtesy of Karl-Ludwig Poggemon. Published under a Creative Commons License.