Several years ago, I spent the night carousing in Prenzlauer Berg. As things broke up after two, I realized that I had stayed out too late – which meant until after the north-south U-Bahn lines had stopped running. In those days, I was living in Neukölln which, for those unfamiliar with Berlin, is a considerable distance. But, mired in penury at the time, and being kind of cheap to begin with, I resolved to make the journey on foot.

Berlin has many fascinating and distinctive qualities. The one that soon absorbed my attention on that particular night is its almost complete lack of public loos. By the time I reached Alexanderplatz, my needs in this regard had pretty much pushed all other thoughts from my mind, and I spent a rather frantic half hour looking for a place to do my business undisturbed. Discombobulated by my search, as well as by a large dose of lager, I contrived to walk out of the square on its eastern rather than its southern side.

It took the best part of an hour for me to realize my error. By then I had entered a maze of large apartment blocks and industrial facilities. The hour was late; there was no traffic and no sign of man or beast save for the occasional lighted window far up in the blocks. The darkness had become palpable, like a thick blanket pierced intermittently by the streetlights’ sodium glare. I finally turned around, retracing my steps to the Alex, and then southward, finally hitting the Oranienstraße, at which point I was finally sure I knew where I was.

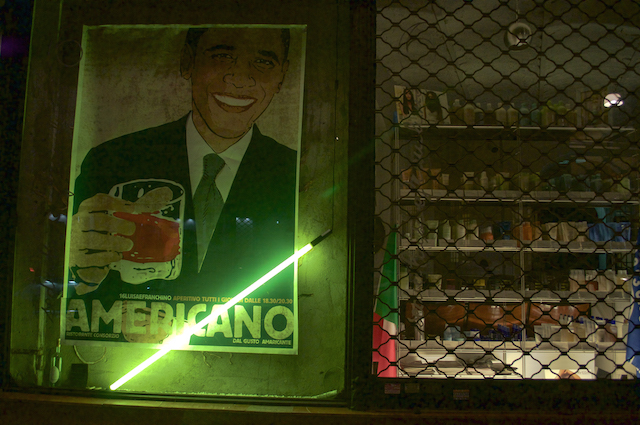

From there to Kottbusser Damm, and then down the Karl-Marx-Straße I passed row upon row of businesses that I had only seen in livelier hours. It was as if the night had stripped away their living qualities, leaving behind only skeletons. In an odd way it was like seeing familiar scenes again for the first time, with the darkness, somewhat ironically, framing them in a different light. And here and there, I met fellow walkers in the night, some late night revelers, some benighted souls, and others on some errand or other that kept them out in the nighttime city.

I was reminded of the sojourn often while reading Matthew Beaumont’s recent book, Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London (2015). Beaumont has taken on the task of a longitudinal history of walking in the city at night between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries and the results are compelling. The night begins as a background for suspicions and misdeeds. Beaumont paints a fascinating picture of the ways that life in the nighttime streets of 16th century London was heavily shaped by class and gender.

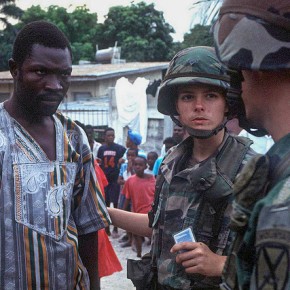

Nobles could be out carousing if they liked without much to fear from the night watch. Those of lower standing were likely to be tossed into jail if they could not provide satisfactory explanations for being out and about, or sufficient bribe money. Women of whatever station stopped by the night watch were generally assumed, to paraphrase Benjamin Butler, to be women of the town plying their avocation.

Much of this remained the case throughout most the roughly four centuries discussed by this book. What began to change by the middle of the eighteenth century was the overwhelmingly negative characterization of night. Night as a time of foul reeks and criminality gave way, in the course of the Enlightenment and the parallel spread of rationalism, to a more nuanced view, one that included that idea that night could provide a new and, in some senses, clearer medium for understanding the world around us and ourselves.

There is an interesting homology here between Beaumont’s work and that found in Walter Benjamin’s expansive and unfinished Passagenwerk. For Benjamin, the construction of the Parisian arcades in the 19th century was both a cause of and a response to new modes of being in the city. Beaumont’s structure is more coherent, or at least less parataxical. His period is longer, four centuries as opposed to Benjamin’s focus on the 19th, and his style has more elements of narrative than Benjamin’s montages. Still, both works are shaped in important ways by what might, for lack of a better term, be called historical materialist agenda.

For Benjamin, the arcades were, in a fundamental sense, expressions of technological development, both in terms of their construction and of the wares that were displayed beneath their shelter. The human type which interfaced with these new modes (over and above the front line consumers) was the flâneur. This variety of being, made possible by the rise of urban consumer culture, was drawn by Benjamin from the work of Charles Baudelaire as archetypal of the experience of urbanized modernity.

In his Political Romanticism (1919), Carl Schmitt had prefigured this character as indicative of the underlying pathology of the modern: the focus on process and the inability (or unwillingness) to act decisively. For Benjamin, on the other hand, the flâneur was an expression of the rising consumer culture and the specifically modern experience of the commodity form. In Benjamin’s idiosyncratic analysis of capitalism, this ambiguous account of the relationship between commodities and human life occupied a central position.

Beaumont is more down to earth in terms of his historical method. His longitudinal account contrasts sharply with Benjamin’s synchronic approach, and his use of evidence (which is copious) is very much in line with modern standards and practices in the writing of history. What stands out in Beaumont’s book is his history of transformation, and the ways that the latter stages of this process reflect a sort of counterpoise to the Enlightenment.

For the nightwalkers of choice in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, night was the obverse side of the light of reason, the Enlightenment sun under whose glare superstition and ignorance could not persist. Rather than viewing night as a time of fear and unreason, as their predecessors had, the night became a new mode of perceiving the world, one in which truths not readily accessible to calculating reason could be accessed.

Beaumont’s contact with historical materialism comes with his relentless pursuit of the ways that class shaped the experience of nocturnal hours. Some men, poets and other creative types, might walk at night out of choice, as well as out of need. But for a large proportion of noctivagants, peregrinations in the darkened city were a matter of having nowhere else to go. This, in a sense, is a model for our own experience of urban modernity.

Night has become a free space for revelry, for the consumption of artistic commodities and (much like it has always been) discharging of libidinal energies. But these activities have been worked smoothly into the structures of the commodity culture, having mostly lost whatever socially marginal qualities they may have had. And there are those, walking the nighttime street and inhabiting its darkened niches for whom nightwalking is a matter of necessity, rather than choice. For these people, the night remains a cloak in which to hide, a means of preserving their existence in the interstices of a commodity culture in which they have little or no place.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.