From the moment Barack Obama moved into the White House, conservatives have been turning to him for sustenance. They know they can rely on him to recharge their ideological batteries. In the suburban and rural enclaves where the right is strongest, particularly in the South and Southwest, trying not to find public expressions of hated towards the President is almost impossible.

But as an increasingly relaxed Obama enters the home stretch of his eight years in office, the Republican Party’s dependence on him is looking increasingly problematic from the standpoint of strategy.

While conservatives have been exploiting a backlash against the perceived excesses of the 1960s for decades, it seems unlikely that their antipathy towards the President will have the same staying power.

For one thing, Obama is almost certainly going to enjoy the same sort of post-White House rehabilitation that his Democratic predecessors Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter did. More importantly, too many Americans recognize that the perceived excesses of the Obama years just weren’t that excessive. When a national health care plan enthusiastically supported by health insurance companies and the right to marry whom you desire constitute the outer limit of “radicalism”, it’s hard to make a convincing case for turning back the clock.

To be sure, conservatives’ dislike for the Affordable Health Care Act hasn’t waned much since it was initially being proposed. But that can largely be attributed to the way in which it was irrevocably conjoined with the President by its designation as “Obamacare”. Indeed, polls have consistently shown that Americans take a much more favorable view of the program when it is described neutrally, without any reference to its source. In effect, the White House has inspired a negative cult of personality every bit as strong as the positive one that swept Obama into office in the first place.

It would be easy to blame this state of affairs in the resilience of outright racism in American life. Yet the reality is more complicated. Yes, there are still plenty of racists in the United States. However, just as the many recent cases of police brutality against African-Americans cannot be reduced to the prejudices of the officers involved, the animus against Barack Obama is not wholly the result of his race. What bothers many conservatives isn’t the President’s blackness itself, so much as the way they see that blackness being mobilized in support of an agenda hostile to their values.

Especially galling, from this perspective, is the way that the Democratic Party has exploited white guilt in pursuit of political goals. Conservatives are no more likely to be racist on a personal level than their liberal counterparts, yet find themselves consistently portrayed that way in the media. Ideological objections to any attempt to increase the federal government’s intrusion into the private sector are consistently recast as a front for deep-seated prejudices. At least, that’s how things look from the right side of the aisle.

Whatever their reasons for hating Obama, though, the problem of what to do after he has left office remains. Although calls to undo everything the President has accomplished might still resonate in the more conservative districts of Congress, that rhetorical gambit is probably not going to win the White House. Nor, for that matter, will Donald Trump’s refried demand for a clampdown on illegal immigration. The Republican Party needs to find some way of articulating a vision for the United States that goes beyond trotting out the same old punching bags to rally the conservative faithful.

This, incidentally, is why the GOP should be hoping that Hillary Clinton wins the Democratic nomination in 2016. Whatever her strengths and weaknesses as a politician — substantially different, it must be noted, from those of her husband — Clinton’s very presence would validate the further recycling of themes from the post-Cold War 1990s.

Given how incapable conservatives presently seem of imagining a post-Obama polity, they would be better off dusting off the weapons they used during the Clinton Presidency than trying to make the case for a future where ideology is no longer inextricably bound up with personality.

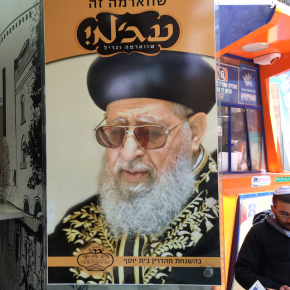

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photograph courtesy of the author.