The signal achievements of postwar Western Europe were undoubtedly impressive: robust welfare states, acceptance and even celebration of previously persecuted minorities, a commitment to peace-first foreign policy, and, above all, the European Community and then Union. But they were also the product of an illusion. Because of depopulation and the delayed effects of decolonization, the continent seemed far more spacious than it does now.

With each passing decade, though, the pressures that had motivated millions to emigrate to places like the United States, Argentina, and Australia in the years leading up to the First World War started to reassert themselves. More and more people from the developing world decided that the economic opportunities available in the homeland of their former colonial “masters” were more than worth dealing with whatever discrimination they would meet. Refugees streaming in from a series of far-away conflicts increased anxieties about the potential scarcity of resources.

By the threshold year of 1989, when Europe’s Cold War political map started to disintegrate, the conviction that the continent could not only match but even outdo the United States as a land of plenty was already fraying. And, while excitement about the Euro’s introduction partially concealed these doubts, there were enough sceptics worrying about its ultimate effects to suggest that the European Union’s “honeymoon” would be short-lived.

It’s important to remember these trends as we contemplate the degree to which the current refugee crisis is impacting the way Europeans see themselves and their neighbors. Not many people remember the massive dislocations throughout the continent at the end of the Second World War, but the sense of despair they produced was transmitted to enough members of the first postwar generation that survival-first reflexes are being triggered in the continent’s elders.

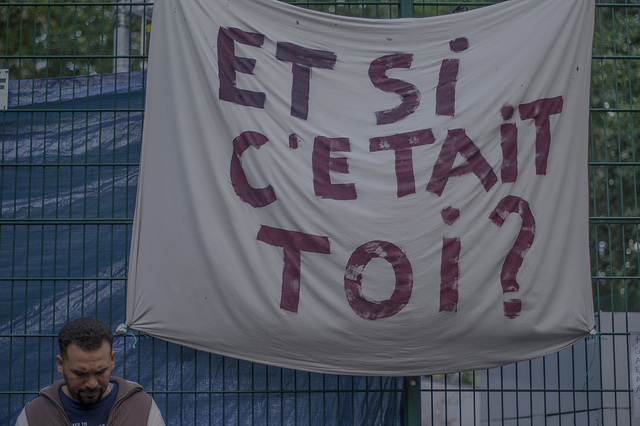

Coupled with the pessimistic vision of those born in the late 1960s and 1970s, who have lived most of their lives in a time of diminishing possibilities, this revival of political atavism has created a leadership vacuum. Even when individuals are moved to do the right thing, they must navigate an atmosphere of panic that makes it far easier to do nothing. That the refugees have been arriving in such large numbers that they cannot be easily “disappeared”, either literally or psychologically, only compounds the problem.

Present-day reality is simultaneously measured against a Golden Age of possibility that is highly unlikely to come again and the darkness that preceded it, when mere survival was all that millions aspired to achieve. When Europeans look out at the refugees who are queuing up for help in their midst, it is hard for them not to wonder whether their own future will be similarly bleak. That is surely why so many of them have struggled to show their better natures.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.