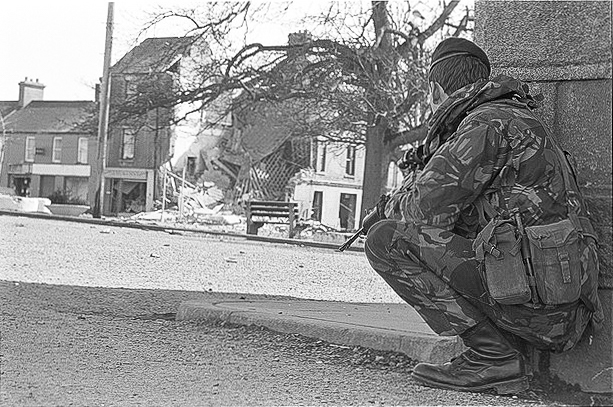

Today, Northern Ireland is officially peaceful. 30 years of intercommunal violence came to a close in 1998, the Provisional IRA disarmed in 2005, and British troops withdrew in 2007 after maintaining a “temporary presence” for 38 years. Governance has since been divided between the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Fein to ensure both communities are represented. Four decades of what Ulster loyalists and Irish nationalists describe as ‘the War’, and the rest of the world knows as ‘The Troubles’, resulted in legal equality and not reunification.

The demographics of Northern Ireland split the region almost evenly between Catholics and Protestants. So any push towards reunification would have to be gradual in line with demographic change. Otherwise it would leave the Protestant community, who are largely unionist and loyalist, feeling disenfranchised. Many loyalists already feel marginalised, and thus turn to bonfires, marches and flags to assert their own identity.

Even before the first shots were fired, the Ulster Covenant was signed by half a million people in 1912. For obvious reasons, the Ulster unionists feel their ‘way of life’ was under threat, first from the Home Rule movement, then from republicanism. Yet it’s plausible the UK could have let Northern Ireland go with the rest of the island. The House of Commons approved the bill for Irish self-rule in 1914. This would have devolved power to Dublin and kept Ireland within the UK.

The First World War postponed the implementation of this plan, and Irish republicans took matters into their own hands in 1916. The British government repressed the insurrection, but it was too late. Once the First World War was over, the Irish war of independence began, and the unionists felt the British state would always secure their position. Indeed, the British government and the Free State partitioned Ireland between North and South.

Ironically, there was never much to gain from holding onto the Irish North, as the region is not home to plentiful resources. Nonetheless, the loss of the North would cost any UK government political capital. This would explain why Labour and Conservative governments were so eager to regain control over the situation. As the Troubles reached their apogee, few politicians could afford to look soft on the IRA. But this often had unforeseen consequences.

Taking a stand

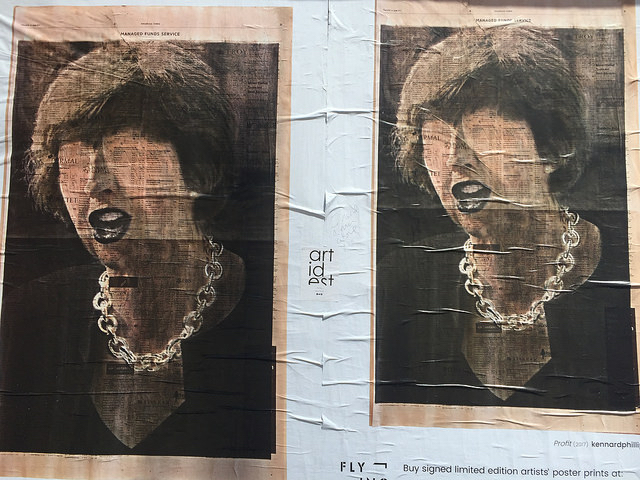

In the aftermath of Airey Neave’s assassination, Margaret Thatcher was eager to appear tough on the question of Northern Ireland. When the Maze Prison protests reached their height in 1981, Margaret Thatcher stood and watched as Bobby Sands and his fellow inmates starved themselves to death. She succeeded in maintaining her image as a stalwart right-winger. Still, the Maze Prison struggle was a major breakthrough for Sinn Fein.

From his prison cell, Bobby Sands ran as a Sinn Fein candidate and won a seat in Parliament shortly before his death. The hunger strike won public sympathy for the republicans and it gave Sinn Fein mainstream status. This was the beginning of the so-called ‘Armalite and ballot box’ strategy. The idea being that the struggle could not succeed by violence alone. By 1983, Gerry Adams was elected in Belfast West, and he became the parliamentary face of the republican cause (albeit by his own absence from the House of Commons).

Although, Adams became a mainstream politician, he remained in the same world as his enemies. The electoral success of Sinn Fein was understood as a major threat by Ulster loyalists. The Ulster Defence Association, and its militant wing the Ulster Freedom Fighters, decided to take out the Sinn Fein president. In March 1984, Adams was traveling through central Belfast in his car when the UFF hit team came up beside the vehicle and fired 20 rounds at him. He was hit in the neck, shoulder and arm, but survived to point the finger at British intelligence.

In October 1984, the IRA bombed the Grand Hotel in Brighton in a bid to assassinate Thatcher and her cabinet. In the aftermath the IRA issued the statement: “Mrs. Thatcher will now realise that Britain cannot occupy our country and torture our prisoners and shoot our people in their own streets and get away with it. Today we were unlucky, but remember we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always. Give Ireland peace and there will be no more war.”

Although, the Thatcher government was known for its hardline approach, the UK and the Irish government did negotiate the Anglo-Irish agreement in 1985. This was not a step towards serious concessions. The UK would allow Ireland to play an ‘advisory role’ in the governance of Northern Ireland, but it would also enshrine the constitutional status of the Six Counties. But it did allow for reunification, if a majority in Northern Ireland want it.

For these reasons, the Anglo-Irish agreement was heralded as a triumph by the Thatcher government, but it was also rejected by republican and unionist politicians. Even though the agreement laid out principles for devolution and power-sharing, the fundamental problems, particularly of the occupation, remained unresolved. It’s probable that the Thatcher government was eager to appear more conciliatory to secure greater leverage. But it failed.

Exhaustion sets in

The scale of violence continued to reach new depths. The Enniskillen bombing on Remembrance Day 1987 killed 12 people and injured over 60 others. The IRA claimed it was targeting the Ulster Defence Regiment in response to the attempts by the UK to secure the extradition of paramilitaries from Ireland. It had the exact opposite effect, the carnage bolstered public support for extradition. The IRA disbanded the unit responsible and even apologised.

At the time, the Thatcher government was facing accusations that it was presiding over a shoot-to-kill policy on members of the IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army. The RUC had shot and killed members of the IRA at checkpoints. On other occasions, the SAS carried out clandestine operations to assassinate IRA members. The most famous case being Operation Flavius, in which the SAS was deployed to kill three IRA members in Gibraltar in 1988.

At the funeral of the three men, Ulster loyalist Michael Stone set upon the cemetery with grenades and pistols. He began lobbing the bombs at the mourners and firing at them. Three people were killed and over 60 sustained injuries before Stone was captured by the police. The scene was captured by a film crew, and the footage left the world horrified. It was a picture of how wretched the conflict had become.

Around this time, veteran Irish republican Sean MacBride predicted that the Troubles would end with a political solution, within 20 years, for three reasons: paramilitaries on both sides are exhausted, the British people don’t care about it, and the British government was increasingly unwilling to meet the costs. By the early 1990s, John Major presided over secret talks with Sinn Fein and the IRA. This eventuated in Major’s declaration of ‘peace’.

The IRA had absorbed the energy of the civil rights movement after the riots of the late 1960s and Bloody Sunday. Likewise, the Ulster Volunteers Force and the Ulster Defence Association recruited great swathes of working-class Protestants in the wake of Bloody Friday – when the IRA set off over 20 bombs in less than 10 minutes. By the early 1990s, both communities had shed a lot of blood and were tired of the violence. A year after Major’s declaration, the paramilitaries announced a ceasefire.

The end game

Tony Blair finished where John Major left off. The Good Friday Agreement was approved by referendum – it won 71% of the vote. The battle lines between republicans and unionists in Northern Ireland were really about what the Six Counties should be. It’s much less about the UK than it may appear. After the Troubles ended, it was possible for Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness to team up in Stormont, because they shared common ground: the province didn’t need to be ruled from London.

Devolution and power-sharing allowed both sides to ignore the rest of the UK to some extent. Like all nations, the United Kingdom is an imagined community, but it’s also a special case. It’s a cluster of imagined communities. The English tend to see Britain as Greater England, while the Scots and the Welsh take a different view unless they’re nationalists (in which case they also see the UK as an extension of England). The fact that the Scottish nobility played a significant role in the British ruling-class and colonialism doesn’t enter into the picture.

Typically, the nationalist forces define themselves against the Union, this is as much true of English nationalists as it is of their Welsh, Irish and Scottish counterparts. The English nationalists see the Union as granting too much to ‘smaller nations’ by way of Parliament and the distribution of tax revenue. The problem was always the unitary nature of the British state, which has not been properly addressed, while devolution has been pursued in an ad hoc fashion. We’ve yet to see the final results.

Photographs courtesy of Burns Library. Published under a Creative Commons license.