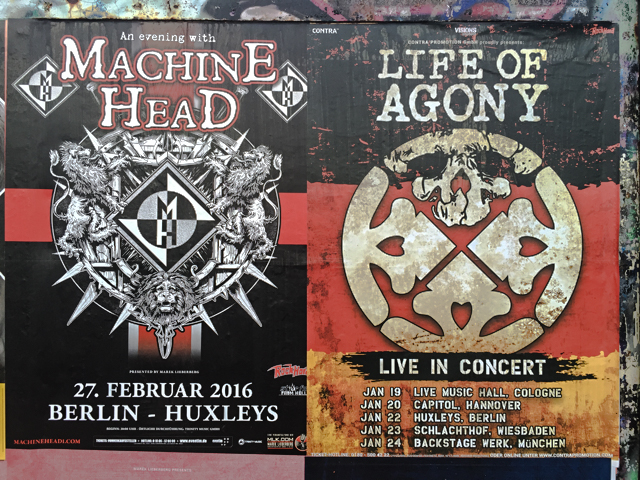

There is a kind of literalism that permeates metal culture when it comes to the word ‘metal.’ Metal is hard, unyielding, unbreakable, weaponised, destructive etc etc. Metal is a metaphor that is applied to the music and to its culture; it represents an ideal as much as a description. That is why images of metallic objects are so common in album artwork and logos: metal bands sound and look like metal. And that is why Life Of Agony and Machine Head proudly display elaborate metallic broach-like crests. Simple, right?

Well yes, but the metaphor proves more fragile than one might expect when exposed to closer scrutiny. As a class of element or alloy, a metal can be heavy and stable, or it can be light and volatile. A metal can be steadfast in refusing to bond with other elements, or it can be promiscuous in its chemical relations. A metal can only exist in the hottest or the coldest of temperatures.

All told, the concept of metal that is generally used as a metaphor for a kind of music and culture, is in fact a very limited and impoverished one – the kind of concept that shouldn’t survive a 12 year old’s encounter with the periodic table in chemistry class.

Of course, even a cursory scrutiny of the diversity of metal today demonstrates that the more simple-minded (pre-lapsarian?) concepts of metallic elements do not even apply to much of metal music. Take Machine Head. Sonically they appear hard and uncompromising, but lyrically they exude brittle vulnerability. ‘Five’ , in which Rob Flynn recounts his childhood experience of child abuse, is a song of being broken irrevocably. It is metal, but it is not steel.

So the metallic crests that adorn Machine Head and Life Of Agony’s tour posters, while they might seem to be emblems of sturdy invulnerability, may be something else. Metal can be as malleable and ephemeral as plastic; a malleability and ephemerality that coyly disguises itself unless one is ‘in the know.’ Viewed on a flag-like background – and in Germany to boot – these crests seem to evoke the cold hard steel of militaristic nationalism (or, perhaps, a quasi-medieval knight’s banner). But this metal can be manipulated, bent out of shape, in ways that are anything but martial.

Commentary by Keith Kahn-Harris. Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.