In the week following David Bowie’s death, a period my friend Ann Powers referred to as “sitting shiva”, my social media feed was dominated by content related to his career. Personal reflections on his impact, pieces about his career and countless links to clips testified to his cultural significance. At times, this collective outpouring felt like a desperate attempt to assert that we all still had something in common.

Or that’s how it seemed to me, as I marvelled at just how many people I know were deeply moved by Bowie’s example. Regardless of their age, sexual orientation, or racial identification, my acquaintances — a more accurate term than “friends”, though some of them are surely both — indicated that his death required more than a passing acknowledgment. The loss had to be publicly commemorated, over and over, in order to preserve the sense of community it had activated.

I shared in this conviction, even though my own investment in Bowie was more modest than most. It felt good to belong, even if I lacked the proper credentials. Because I was so aware of my own marginality, though, I couldn’t help but wonder if there was anything that could hold this community together aside from such shared acts of mourning.

Technically, of course, the fact that we are all in contact with each other through social media is sufficient to make a more sustained sense of solidarity possible. But there aren’t many occasions when it manifests itself so intensely. Political content is a lot more divisive, even when people are supposedly on the same basic side. And it is the rare cultural touchstone that can mobilize responses from even 5% of the acquaintances I see regularly in my feed.

So when that does happen, the resulting impression is that those far-flung individuals might constitute a meaningful community, a “we” with the potential not only for passive staying power — itself no guarantee at a time when the life-span of social media platforms is more likely to be measured in years than decades — but active work in concert.

The first-person plural is tricky, though. Every “we” is the product of a power move, indicating that the person who posits it feels authorized to privilege what its members have in common over the many differences that could still divide them. Even at its most well-intentioned, as a gesture of hope, this grammatical leap usually still feels like an act of coercion. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s famous vision from The Social Contract of a political community formed spontaneously by all of its members is an ideal seldom approached.

In the case of David Bowie’s death, this problematic aspect to community is particularly clear. The people in my feed posted statement after statement about what he meant to them personally, consistently noting that his example made them feel better about not fitting in, being the exception to the rules imposed by the formal and informal communities in which they hag grown up. To be sure, many of them also added that this confidence led them to seek out like-minded individuals and, ultimately, a sense of solidarity in the margins. But it was also apparent that any attempt to pack this set of misfits into the neat-and-tidy box of a sustained “we” would have undermined the differences they cherished.

Even if we leave this difficulty aside, though, there are reasons to be dubious of the capacity to build and sustain collectivity through cultural means. Perhaps the most challenging aspect of contemporary cultural analysis, like its political counterpart, is the degree to which experience is pre-filtered. The more people rely on social media for information, the more likely that it will come from points of view similar to their own. When almost everyone you know seems to be thinking about the same few topics, it feels logical to presume that they are just as important outside of the networks to which you belong. But that conclusion is frequently wrong, sometimes dramatically so.

I was given a powerful reminder of this fact in the wake of David Bowie’s death. I had assigned the students in my new media course a questionnaire on the first day of class in order to assess what they already knew about the material we would be covering in the semester ahead. I was sure that almost none of them would have heard of Walter Benjamin and suspected, in light of how little emphasis is placed on social studies in American high schools, that few would have a clear sense of when the printing press or telegraph were invented. And I was right.

What surprised me, though, was the lack of knowledge many of them exhibited about present-day culture. Knowing that Bowie’s death had been “above the fold” news throughout the developed world and that his new album had shot to the top of the charts, I had asked them to explain briefly who he was and for what work he was best known.

Considering that over half of my own social media feed has been devoted to him since Sunday, I figured that they should at least be able to provide a basic summary of his historical significance. But as I read through the completed questionnaires, I realized that most of them had barely heard of him prior to this week and some still had no idea who he was. A sizeable percentage of the students who did recognize his name only identified him as an actor, which was true, but were unable to name any of the films in which appeared. One of them described him as President Obama’s “fashion consultant.”

This lack of knowledge reflected a generation gap, of course, since Bowie hadn’t been very active in the decade-plus during which they were likely to have been aware of popular culture. Yet there seemed to be more to it than that. In this questionnaire I had also asked them to comment on a short, parodic clip playing off the blockbuster new film Star Wars: The Force Awakens, which has set one box-office record after another since its December release. My intention was to see how much thought they had given to fan culture and the complexities associated with user-generated content. What I found, though, was that a good number of them knew very little about the Star Wars universe.

Considering how much I had been bombarded with content related to the film both in the traditional media and my social media feed, I initially found this astounding. The more I thought about it, though, the more it became clear that this lack of knowledge on their part was also partially the result of a generation gap. To many of them, Star Wars was just another franchise to which they were expected to pledge allegiance by people my age and older. Even though the new film was meant to win them over, in theory, it still didn’t feel like their culture.

Reading their other responses to the questionnaire, though, it was painfully apparent that figuring out what that culture might constitute was an exercise doomed to frustration. There was little consistency in their answers to questions about books they had read, music they listened to, or even films and television shows they had recently seen. Simply put, the likelihood of ever assembling a “we” out of their cultural pursuits — or, in some cases, lack of pursuit — was slim.

To someone of my generation, this may seem like a depressing prospect. But I do think that this absence of commonality offers a useful political lesson. When the only way that people can come together as a collective is by consciously willing themselves to do so, rather than relying on shared interests or experiences, there may be greater potential for making whatever “we” results last, precisely because its fundamental precarity is not obscured by any assumptions about what its members share.

That’s why, even if people feel the need to publicly mourn the passing of stars like David Bowie, they shouldn’t necessarily mourn the passing of the cultural moment they have come to represent. To invoke one of the man’s last great songs, as long as there’s “me” and “you”, it’s an open question where “we” can be found, one that it may do more harm than good to close.

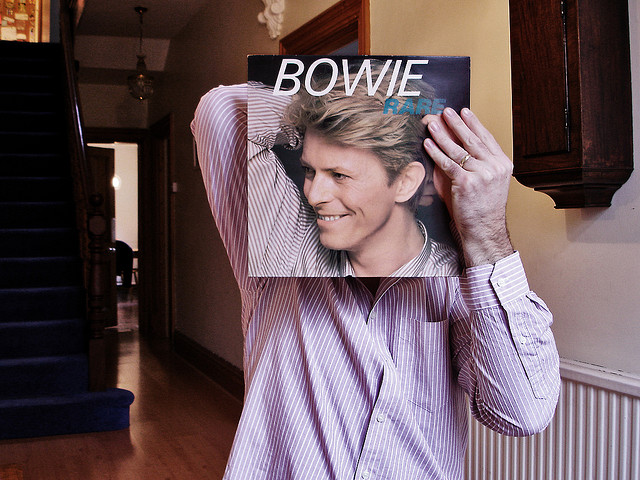

Photo courtesy of Tim Caynes, published under a Creative Commons License.