Sometimes hardship leads to serendipity. Since I came down with a bad respiratory infection a few weeks ago, my voice has been reduced to a scraping sound. This has forced me to modify my teaching, finding as many ways as I can to avoid talking. It’s why, instead of explaining the rise of the Khmer Rouge to my freshman seminar, I showed them a video instead.

We’re currently reading Vaddey Ratner’s In the Shadow of the Banyan, the lightly fictionalized memoir of a young girl whose life was turned upside down when Phnom Penh fell in 1975. It’s a harrowing tale, despite the author’s efforts to communicate her remarkable capacity to find beauty in terror. But as rich with detail as the book is, my students hadn’t seemed to register its full implications.

Part of the reason, no doubt, is that they are woefully ignorant of geography. Few of them had ever learned anything about Cambodia. Fewer still had any idea where to find it on a map. And since the novel begins in medias res, right before the Communists enter the capitol, the background necessary to understand what is happening and who can plausibly be assigned blame for it was utterly lacking. They might as well have been reading make-believe.

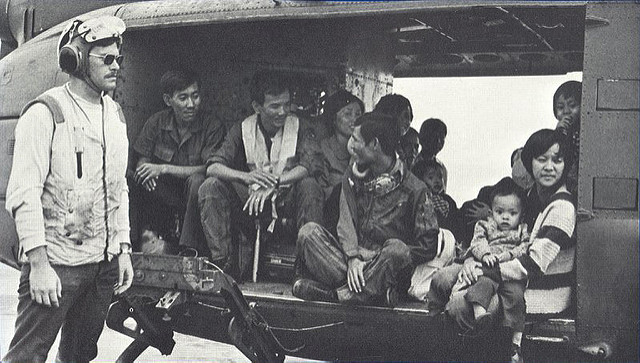

My intention had been to remedy this deficiency with a short lecture covering the basic outline of Cold War history in Southeast Asia. That would have helped matters, but only up to a point. By deciding, on the spur of the moment, to show them the fifty-minute BBC documentary I found on YouTube instead, I was able to educate them not only about the horrific reality of Phnom Penh under siege but also the extent of American complicity in the rise of the Khmer Rouge.

For today’s college students, who are unlikely to read a newspaper or watch the news on television, but get their news in small bits and pieces over social media, just being compelled to watch a coherent historical narrative can be a transformative experience. Witnessing their vague understanding of the Vietnam War be gradually replaced by a more expansive, detailed and relational account of the conflict was intense.

Liberated from the pre-judgments they were brought up around in the wake of 9/11, which largely prevent them from making sense of the United States imperial legacy in the Muslim world, they were able to “put two and two together”, as the saying goes, and grasp connections between policy decisions and human suffering in ways that had previously eluded them. I could hear them do so, as they gasped and sighed at footage of Henry Kissinger talking in circles about the Nixon Administration’s clandestine air war in Cambodia.

Many of them were already aware, however vaguely, of the devastation in Syria and the refugee crisis in Europe to which it has led. But it was clear that their perception of those news stories was radically enhanced by virtue of the analogy which Cambodia makes possible. It may be depressing to realize that we are basically repeating some of the worst mistakes of our recent history, yet this state of disillusionment is greatly preferable to the alternative. Now I just need to play them the Dead Kennedys’ song.

Photograph courtesy of Image Works. Published under a Creative Commons license.