Even now, long after Donald Trump has ascended to Republican frontrunner for the presidency, people are still talking about him the way they did a year ago, when his candidacy seemed more of a sideshow than a serious threat to politics-as-usual. It’s a state of affairs the man himself seems eager to perpetuate, promoting his brand at the expense of traditional propriety. The strange press conference he held in the wake of winning the Michigan and Minnesota primaries this past Tuesday, in which he proffered Trump steaks and Trump magazine — both products that have been discontinued — to assert his prowess, is only the latest example. Indeed, he frequently seems to engage in self-parody, speaking the way his impersonators do, exaggerating his own already-exaggerated mannerisms, as if he could thereby regain full control of his image.

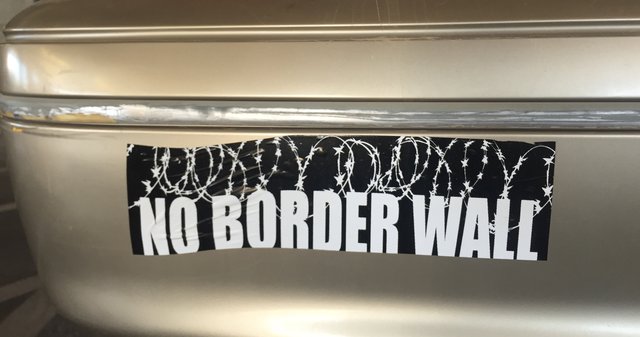

Of all the button-pushing statements Trump has made since making the announcement that he would run for office, the best known is the one that helped move him from the margins to the middle of political discourse, his declaration that he would “build a wall” on the American border with Mexico to keep out illegal immigration. Never mind that the number of people making the passage has dropped sharply since the economic crisis of 2008 or that, in high-profile places like Tijuana, there already is a formidable wall dividing the two nations. For a sizable percentage of the American electorate, the idea that a politician would have the nerve to declare what they had already been saying in private resonated powerfully.

Comedians were quick to pounce on the seemingly primitive nature of Trump’s plan, making it seem laughable in an era of unprecedented globalization. Their best routines turned on the realization that it wasn’t just the specific problem of the border with Mexico that makes Trump’s plan appealing to his supporters, but the broader principle it stands for, a kind of extreme protectionism at odds with the reality of transnational capitalism and, it must be noted, his own business practices. The irony that Trump’s iconic red baseball caps emblazoned with the injunction to “make America great again” were being made in China reinforced the absurdity of his rhetoric.

As astute commentators have started pointing out, though, no matter how much of a hypocrite Donald Trump may be, much of his surprising political strength derives from the fact that he is willing to tap into fears that his rivals discount or outright ignore. The impulse to respond to the threat of intrusion by building a wall is deep-seated in the human psyche, even if, as in the case of the Great Wall of China and the Maginot Line, doing so often proves ineffective. At a time when most politicians seem like the weak-spined lackeys of corporations that want every border made permeable to the flow of capital, Trump’s apparent eagerness to be a traitor to his class is perceived as a welcome alternative.

The people who still make fun of him for advocating wall-building or who advance high-minded critiques of his racist isolationism miss this crucial psychological component to his candidacy. In a way, Trump’s supporters are finding a way to turn his obsession with branding to their own ends. His name doesn’t just stand for quality in their eyes — if it even did to begin with — but a refusal to accept what most people in positions of power take for granted. At a juncture when the border between politics-as-usual and business-as-usual seems to have been damaged by repair, Trump’s unconventional approach to business may give him a credibility that the politicians he is running against cannot hope to match.

Photo courtesy of the author.